What Do the Right Thing can teach us now

The iconic film feels just as relevant today as it did 30 years ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over the weekend, director Spike Lee released a short film, "3 Brothers," which intercuts footage of the deaths of Eric Garner in 2014 and George Floyd last week alongside the death of the fictional Radio Raheem, from his 1989 film Do the Right Thing. "This is history again and again and again," Lee said after the short aired on CNN. "This is not new. The attack on black bodies has been here from the get-go."

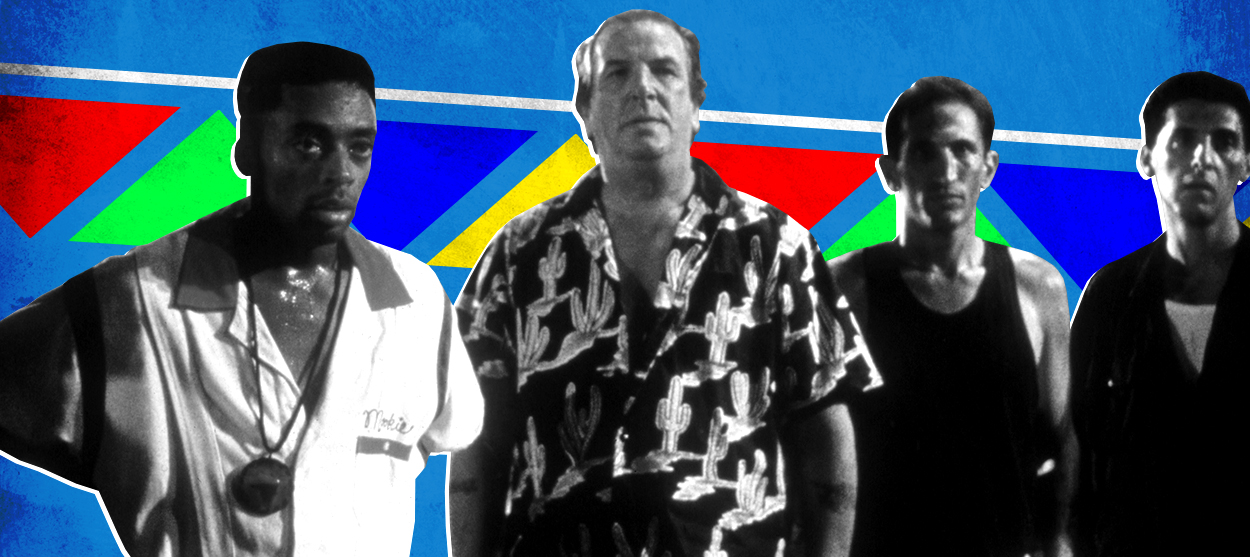

It's near impossible to ignore the parallels between Do the Right Thing and the murder of George Floyd. The film follows a day-long escalation in tensions between Italian-American pizzeria owners and their black clientele, culminating with white police officers asphyxiating one black patron, Radio Raheem, during a botched apprehension, prompting Radio's friend and pizzeria employee Mookie (played by Lee) to throw a trash can through the restaurant's window and incite a riot. Debate has long swirled around the question implicitly posed by the movie's title: Did Mookie do the right thing when he threw the trash can?

It's human nature to try to land on a definitive answer — to label Mookie's actions as either "right" or "wrong." But Do the Right Thing was never really asking that question. Rather, the film has always been an appeal for empathy, and one many of us still seem incapable of heeding three decades later.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When white critics first saw Do the Right Thing in 1989, the concern echoed in many of their reviews was that the film might make (as Lee later put it) "black people … run amuck." Newsweek's Jack Kroll wondered "how will young urban audiences — black and white — react to the film's climactic explosion of interracial violence," describing it as "dynamite under every seat." David Denby, then at New York, claimed Lee's "dramatic structure … primes black people to cheer the explosion as an act of revenge" and said "if some audiences go wild, [Lee is] partly responsible." Joe Klein, also at New York, wrote in an editorial that the film would open June 30 but "in not too many theaters near you, one hopes" because of its "dangerous stupidity." As Lee has since said, "These reviews were absolute racism. Racism." The anticipated riots, notably, never materialized.

Still, the vehement condemnation by the film's initial critics made it clear enough: Mookie had not done the right thing. The riot, in their opinion, resulted from the protagonist succumbing to "hate" in the ongoing battle with "love" that is poetically described by Radio Raheem earlier in the film. Do the Right Thing seems in some ways to encourage this binary of choices, too, with the recurring photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. shaking hands with Malcolm X. The movie ends with the leaders' opposing appeals — King's for peaceful protest and Malcolm X's advocating for righteous self-defense. But the quotes share the screen: Lee, it seems, isn't advocating for one method over the other, but rather for understanding why Mookie would be driven to violence.

Do the Right Thing is peppered with allusions to the unjust deaths of black Americans in the 1980s: Michael Stewart, who died in 1983 after 13 days in a coma stemming from police brutality during an arrest for writing graffiti; Eleanor Bumpurs, an elderly disabled woman who was shot by the NYPD in 1984; Michael Griffith, a black man who was killed by a white mob in 1986; Tawana Brawley, a 15-year-old who accused four white men of raping her. It is dizzying to consider the long list of atrocities that followed those tragedies.

Like Radio Raheem, George Floyd was unarmed and suffocated to death by a white police officer. And as Radio's death in Do the Right Thing, Floyd's death was a breaking point. And we are embroiled in a near-identical — but no longer hypothetical — debate today, in the wake of Floyd's death, as we were after the release of Lee's movie. We're asking: Is violent resistance the "right" thing? President Trump and many of his supporters think not. He has used the racially-dehumanizing word "thugs" to describe those protesting against police brutality. Meanwhile, there's been an overwhelming outpouring of support for black Americans, whose patience with conventional routes for change has, understandably, worn thin.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It is tempting to reduce complicated questions — like how to reckon with America's long and shameful history of racism — to the simplistic values of "good" or "bad" to make sense of our own emotional reactions. In this sense, the debate about whether riots and heated protests are "right" or "wrong" is largely unproductive. The question worth pursuing here is why one might be motivated to participate in violent resistance in the first place. What pushes Mookie to throw the trash can through the window? He knew there would be no accountability for the murder of Radio Raheem unless he took action into his own hands. The police officer who placed his knee on Floyd's neck until Floyd took his last breath was not immediately arrested. It was only after protesters took matters into their own hands that he was taken into custody and charged. And legal justice in the Floyd case is still far from a certainty.

Can we empathize with these motivations? If so, we may be better positioned to understand the protesters who take to the streets in response to racial violence, risking their physical safety and lives to make themselves heard, whether we agree with their methods or not.

Tellingly, Lee has said that despite frequently being asked if he thinks Mookie did the right thing, "not one person of color has ever asked me that question." Likewise, as DePaul University professor Kelli Marshall has anecdotally reflected, every year she shows her film students Do the Right Thing, "most students of color feel Lee's character 'did the right thing' while the majority of white students cannot understand why Mookie 'would do such a thing to his boss.'" White people need to examine how much of their assertions that Mookie did the wrong thing are because they are afraid of what it might mean if inciting a riot was not just a last resort, but the right means to achieving justice.

Spike Lee, for his part, has been clear all along that he doesn't endorse violence. "I am not condoning this other stuff," he told CNN this weekend, "but I understand why people are doing what they are doing."

Only from this position of introspection and empathy might we finally move toward the kind of conversation Do the Right Thing urged viewers to have 31 years ago, and which remains so viscerally relevant today. This conversation requires that we hear the cries of the protesters who are at their breaking point, and heed their demands for accountability and justice.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.