We're missing the most glaringly racist brands

Native American sports mascots are a bigger no-brainer than Columbus statues

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is time for spring cleaning in America. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests stemming from the police killing of George Floyd, parts of our culture that had long managed to avoid deeper introspection are being dragged into the disinfectant of daylight. Best Picture winner Gone With the Wind? Yanked from HBO Max until it can be presented with proper historical context. Statues of Christopher Columbus? Bring 'em down. Even Aunt Jemima syrup isn't safe.

Being, as we are, a colonialist nation that decimated its indigenous population and ballooned into the biggest industrial power in the world via the use of slaves, it is to be expected that this process is slow, sensitive, and ongoing. As a country, we are holding important and overdue debates about who we choose to continue to honor in the 21st century, and why, and how. But with a renewed and reinvigorated focus on representation, it is shocking that at this point we continue to ignore what might be the lowest hanging fruit of all: The country's remaining racist sports mascots.

There are no shortage of articles that condemn franchises like the Washington Redskins, which uses a slur for its team name, or the Cleveland Indians, which is based around a Native American caricature that the team is only reluctantly beginning to distance themselves from. The use of these stereotypes, meanwhile, has been proven to "decrease Native individuals' self-esteem, community worth, and achievement-related aspiration," researchers at UC Berkeley found in February. Plus the mascots are opposed by Native Americans themselves: "I am regularly confronted with mascot images that dehumanize Native Americans as hostile and aggressive," writes Angelique EagleWoman for Indian Country Today. "These images are usually cartoonish depictions of our traditional dress and lifestyle from the 1800s."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Or, as Nick Martin put it for The New Republic this past January: "Native mascots are a monument to racism, just as the Confederate statues that dot public grounds across the country are monuments to racism." It was a percipient observation. As the George Floyd protests have overflowed into a nationwide reckoning with still-standing Confederate statues — most of which date back not to the Civil War, but to the early- and mid-20th century, when they were erected with the specific aim of intimidating black Americans — attentions have also turned to other kinds of monuments. In the U.K., for example, protesters tore down a statue of a slave trader and pushed it into a harbor. But a Winston Churchill monument proved to be a thornier topic, eliciting debate between recognizing the former prime minister's leadership during World War II and his history of racist comments and actions, which were, sadly, not unusual for his time.

Likewise, American cities are now grappling with what to do with their Christopher Columbus statues, as the explorer has been swept up in the momentum of the George Floyd demonstrations. Many such statues were initially erected as gestures of goodwill toward Catholics and Italian-Americans, who faced discrimination for decades, although many modern Italian-Americans agree he no longer serves to represent that interest. "Our country prioritizes the comfort of Italian Americans and how we are going to feel about this instead of centering the voices of native American people," Heather Leavell, the founder of Italian Americans for Indigenous Peoples' Day, told The Associated Press, adding: "Our parents have told us stories about the level of discrimination they faced … We unfortunately allied ourselves with a white supremacist in our attempts to be recognized in this country."

But Native American mascots are not monuments. They're much worse. While monuments are generally erected to honor the legacy of a dead person and are not specifically intended to inspire action on the part of the viewer (that is to say, no one is looking at statues of Christopher Columbus and then prancing off to go fake-discover a continent and terrorize its inhabitants), sports teams do require our participation. We're meant to feel allegiance with them, and to partake in their celebrations, rallies, and traditions. And because Native American mascots were initially born out of dehumanizing stereotypes, intended to channel the ferocity and brutality that a neighboring team might emulate with a mascot that is a tiger or a bear, this means the ensuing engagement with Native American culture is at best shallow, ignorant, and offensive.

Naturally, there are varying degrees of offensiveness here: the Redskins are among the worst, while the Chicago Blackhawks is somewhat more debatable (the National Congress of American Indians opposes all Native American mascots, Blackhawks included). But across the board, the continued use of a Native American mascot practically endorses fans to wear headdresses or "war paint" to stadiums, and to perform offensive war cries or rallies like the tomahawk chop. Stopping fans from acting in such a way, when they ignorantly or arrogantly believe they're supporting the team, has proven to be extremely difficult. In effect, even the most open-minded teams who are still using Native American mascots are inadvertently, but actively, perpetuating racism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By all means, keep tearing down terrible statues and throwing out stereotypical logos. But don't forget about the sports teams, which should not sneak out of this cultural reckoning unscathed. Franchises with insensitive mascots ought to take a good look around them, at the Americans on the streets demanding overdue changes, and take a step toward the right side of history. What better time to commit to out with the old, and in with something better and new?

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article cited the American Indian Center of Chicago's relationship with the Chicago Blackhawks, which ended in 2019. The American Indian Center of Chicago no longer affiliates with organizations that use American Indians as logos or mascots. We regret the error.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

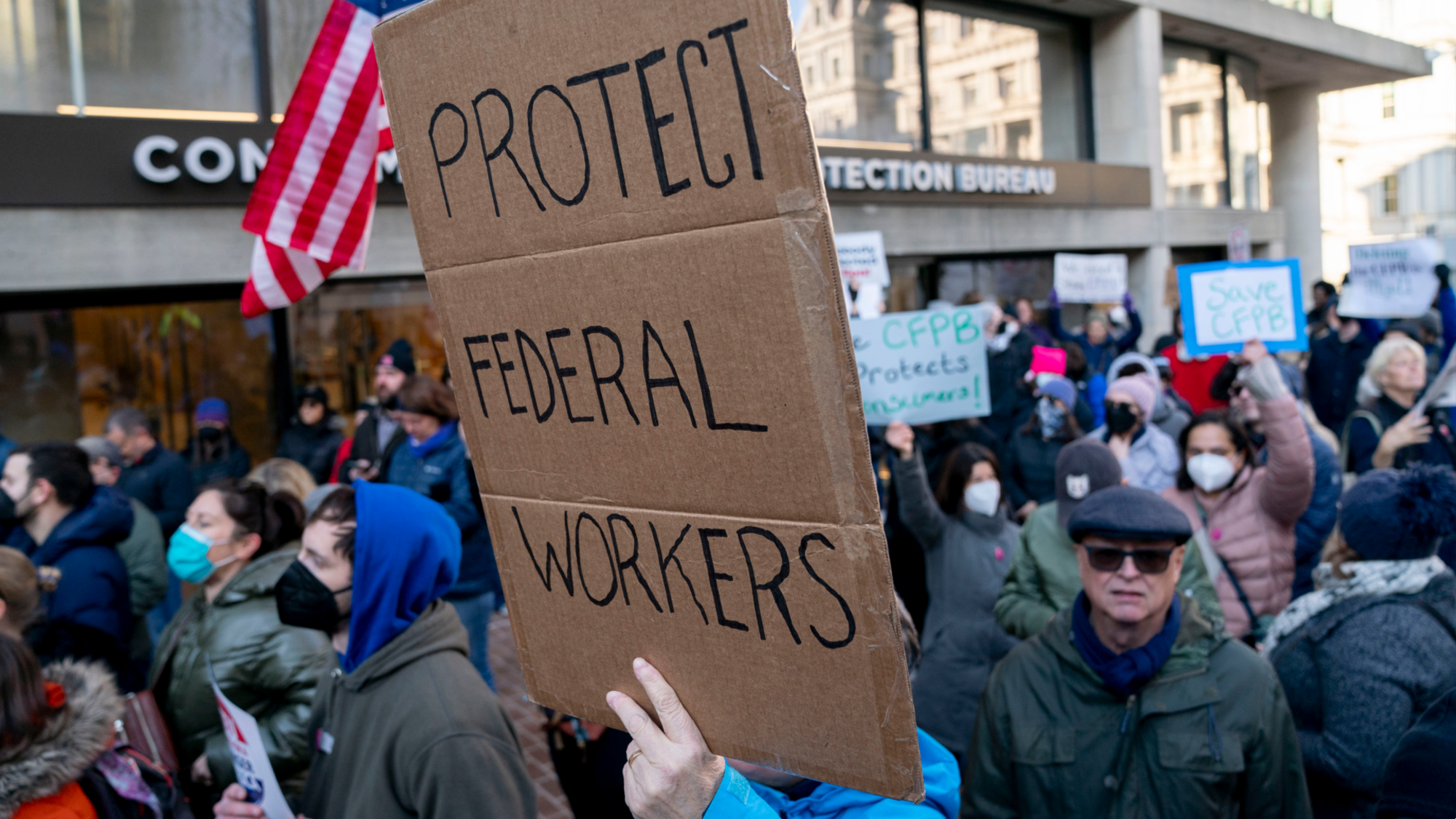

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred