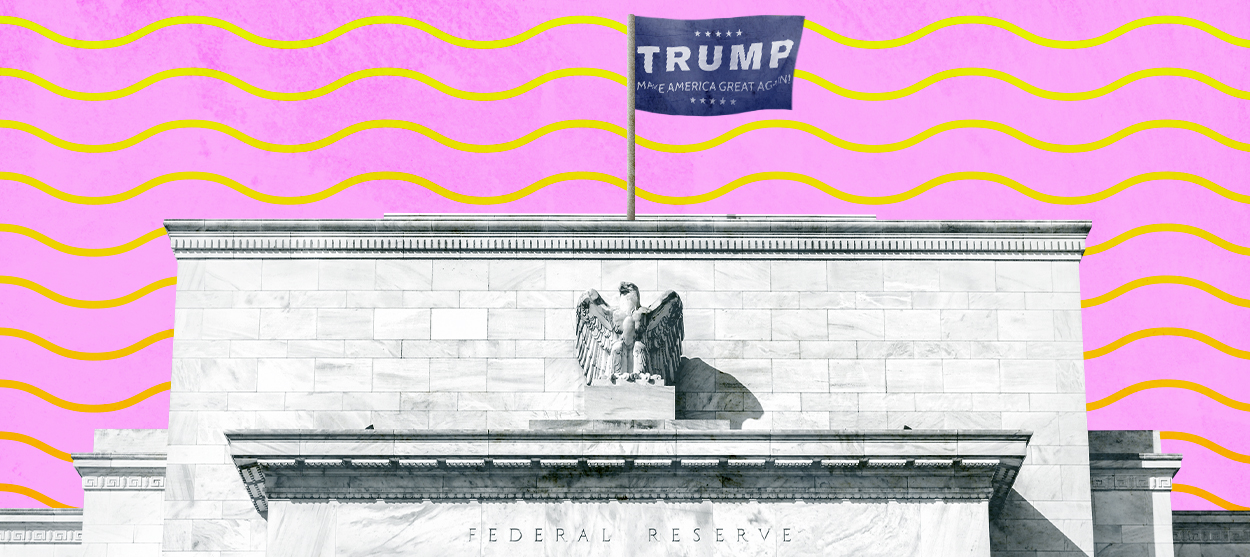

Did the Fed give us Trump?

And will it do so again in November?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sometimes it's hard to know what old rules of politics still apply in the Age of Trump. But this one might: If you're the presidential nominee of the incumbent party, you don't want a lousy election-year economy. And it's also one rule President Trump probably has no interest in breaking. He's pushed for the U.S. economy to reopen as fast and fully as possible during the pandemic.

Four years ago, roles were reversed. Trump was the challenger during a time of economic weakness, while Hillary Clinton was the nominee of the incumbent party. No, there wasn't an all-out recession back then. But things were probably worse than you remember. From the third quarter of 2015 though the third quarter of 2016, the economy grew at a sluggish 1.6 percent annual pace. That compares to nearly 4 percent in the previous five quarters and nearly 3 percent in the subsequent five quarters. So a lull for more than a full year.

And it may have cost Clinton the election. When you dig down beneath those top-line numbers, you can see the economy really did her no favors. A Reuters analysis from last year showed that across the roughly 2,600 counties that Trump won in 2016, GDP growth was barely 1 percent. And about 1,200 of those counties were in a deep recession, with local economies shrinking by close to 4 percent. The Clinton counties, by contrast, saw a healthy average growth over more than 3 percent, faster than the overall economy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Those stats create an interesting lens through which to view comments on Tuesday by Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard about the Federal Reserve's updated approach to monetary policy. The Fed's new "framework" means the central bank will let inflation float above its long-standing 2 percent objective if price increases had been under 2 percent for a long time. And the central bank will no longer view low unemployment as a reason to raise interest rates. "Had the changes to monetary policy goals and strategy we made in the new statement been in place several years ago," Brainard said, "it is likely that accommodation would have been withdrawn later, and the [recent years' job market] gains would have been greater."

In other words, the Fed should have behaved differently the past five years. It should have been less aggressive in raising short-term interest rates from near zero in 2015 to a range of 2.25 percent to 2.50 percent at the end of 2018. When Fed policymakers, led by Chair Janet Yellen, began raising interest rates in December 2015 — the first rate hikes since before the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis — the unemployment rate stood at 5.1 percent and year-on-year inflation was just 0.3 percent. It was a controversial move at the time, and not just because inflation was so low. Even before the interest rate increase, financial conditions had been tightening, especially corporate borrowing costs. In addition, there was big trouble overseas in many emerging economies due to a downturn in international commodity prices, stemming from a Chinese economic slowdown. All this led to a U.S. industrial recession from the middle of 2015 through the middle of 2016, a downturn that badly hurt many areas that ended up being Trump strongholds. As it turned out, the last thing the economy needed was a Fed rate hike and the expectation of many more.

The Yellen Fed soon delayed plans for that series of hikes until the end of 2016. Right before the December 2015 hike, however, Politico ran a piece with this headline: "Could an 'accident' by Janet Yellen derail Clinton?" Turns out, it kind of did. The Fed rate increase was not a lot, but it came at a terrible time. And Trump didn't win by much. A marginally healthier economy in 2016 in some key counties might have been enough to get Clinton first across the finish line.

But 2015 may not have been the only time the Fed helped Trump. It's hard to imagine him getting elected in 2016 without the global financial crisis that ravaged the U.S. economy and greatly undermined confidence in elites. And the Fed played a big role in that downturn, too, when it paused its interest rate cuts in 2008 even as the economy was badly deteriorating. And now the Fed is inadvertently helping Trump for a third time by reassuring markets that it is unlikely to raise rates anytime soon. But Fed Chair Jerome Powell surely doesn't think this will get him a second term. After all, Yellen's accidental help didn't get her one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern

-

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 February

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

Nordic combined: the Winter Olympics sport that bars women

Nordic combined: the Winter Olympics sport that bars womenIn The Spotlight Female athletes excluded from participation in demanding double-discipline events at Milano-Cortina

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred