What do we do about COVID vaccine refusal?

Health-care workers refusing a COVID-19 shot is a troubling sign for the year to come

At Ohio nursing homes, the state's governor said Wednesday, about 60 percent of staff have chosen not to take a COVID-19 vaccine despite their work with the single most vulnerable population in this pandemic: elderly and unwell people in an institutional setting where transmission is often swift and symptoms severe.

In California, many frontline health-care workers are refusing vaccination, too. "At Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, one in five frontline nurses and doctors have declined the shot," the Los Angeles Times reported Thursday. "Roughly 20 percent to 40 percent of L.A. County's frontline workers who were offered the vaccine did the same, according to county public health officials. So many frontline workers in Riverside County have refused the vaccine — an estimated 50 percent — that hospital and public officials met to strategize how best to distribute the unused doses."

And in Wisconsin this past weekend, a hospital employee admitted to purposefully sabotaging 50 vials — more than 500 doses — of the Moderna vaccine by removing it from required refrigeration.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some skepticism of the COVID-19 vaccines was inevitable. We always knew a subset of people medically eligible for the shots would refuse them. But this degree of opposition, especially in the health-care field, is unsettling. One recent survey found three in 10 health-care workers and a nearly identical percentage of the general population are "vaccine-hesitant." How do we handle this?

The sabotage case in Wisconsin is the easiest. As is already happening, the employee should be fired and prosecuted as appropriate.

Personal vaccine refusal is far trickier. Granted, these numbers may be somewhat inflated. They possibly include people who have a legitimate medical reason not to be vaccinated. They certainly include people with a temporary reason for refusal, especially pregnancy or breastfeeding (the Centers for Disease Control doesn't recommend against COVID-19 vaccination for women in either circumstance, but it does caution that data on outcomes there is limited). One of the nurses in the Los Angeles Times story, April Lu, cites exactly this reason for waiting.

Even with those numerical caveats, however, these reports from Ohio and California suggest a startlingly high rate of refusal among health-care workers. "I feel people think, 'I can still make it until this ends without getting the vaccine,'" Lu said of her coworkers who are refusing without a reason like pregnancy. But the trouble is that the main way "this ends" is herd immunity, ideally achieved through widespread vaccination, not further years of wild viral spread and the death toll and social and economic misery that have come with it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But ... what can we really do? We can't fire all the nurses who won't get vaccinated when we're still in the middle of a pandemic. Many hospitals already have a critical staff shortage, so it's just not feasible to say only those who accept a vaccine can work. Sidelining 20 to 40 percent of available doctors and nurses would be catastrophic. An unvaccinated nurse is better than no nurse.

I'm also deeply wary of some proposed enforcement mechanisms. As I wrote in April, immunity certificates with attendant privileges have an obvious appeal, but the precedent of requiring special papers to appear in public is troubling, and the potential for abuse is real. Certificates would also immediately be forged, potentially giving medically vulnerable people a false sense of security.

Centralized vaccination refuser lists, like the one Spain will make and share with other European Union governments, are no better. The Spanish government insists the list will not "be made public, and it will be done with the utmost respect for data protection." But it's hardly unreasonable to default to suspicion of government databases. The terrorist watchlist is a notorious fiasco, and still people propose using it to curtail constitutional rights. It's as if the very existence of such a list cries out for some misuse or another. Moreover, many governments, ours included, have poor digital security and a long record of trampling citizen privacy. Secretive state databases and due process rights are not a great pairing.

I also can't get behind sweeping vaccine mandates for the same principles of bodily autonomy that undergird my opposition to the drug war. I think it's wrong and dangerous and a risk of harming others to use drugs like heroin, and I also think it's wrong and dangerous and a risk of harming others to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine (absent medical exemption, of course). But in neither case can I make the leap to saying the government should be able to dictate what you can or cannot put in your own body — and neither, I suspect, can most Americans. Forcible injections ring every alarm in our political culture, including for Dr. Anthony Fauci and President-elect Joe Biden, who agree a national mandate would be legally and ethically unacceptable.

Smaller, institutional mandates by businesses and schools are better on both counts, but they aren't capable of producing anything close to universal vaccination. I'm not sure anything is. Messaging, celebrity endorsement, and educational campaigns may all do some good, but is it enough? Unless current numbers budge, a lot of vaccine-preventable transmission will happen. Some (perhaps never-to-be quantified) group of people who couldn't yet or couldn't ever be vaccinated will be infected by vaccine refusers. Very possibly some of them will die.

I don't have a solution to recommend here. I don't think there is a good solution.

In six months or so, when vaccines are expected to be available to everyone who wants them, the consequences of refusal will fall much more narrowly on the refusers. But that narrowing won't be absolute. There will still be people who can't get vaccinated who may be infected by those who could but wouldn't. There could even be comparatively accelerated mutation of the virus (requiring an annual vaccine update, like we have for the flu) if it continues to be passed around in evolving form among the willfully unvaccinated.

The best — the only? — thing to do may be vaccination itself for those of us willing to do it, followed by patient personal conversations with loved ones who have trepidation. Get your shot, and tell your friends.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

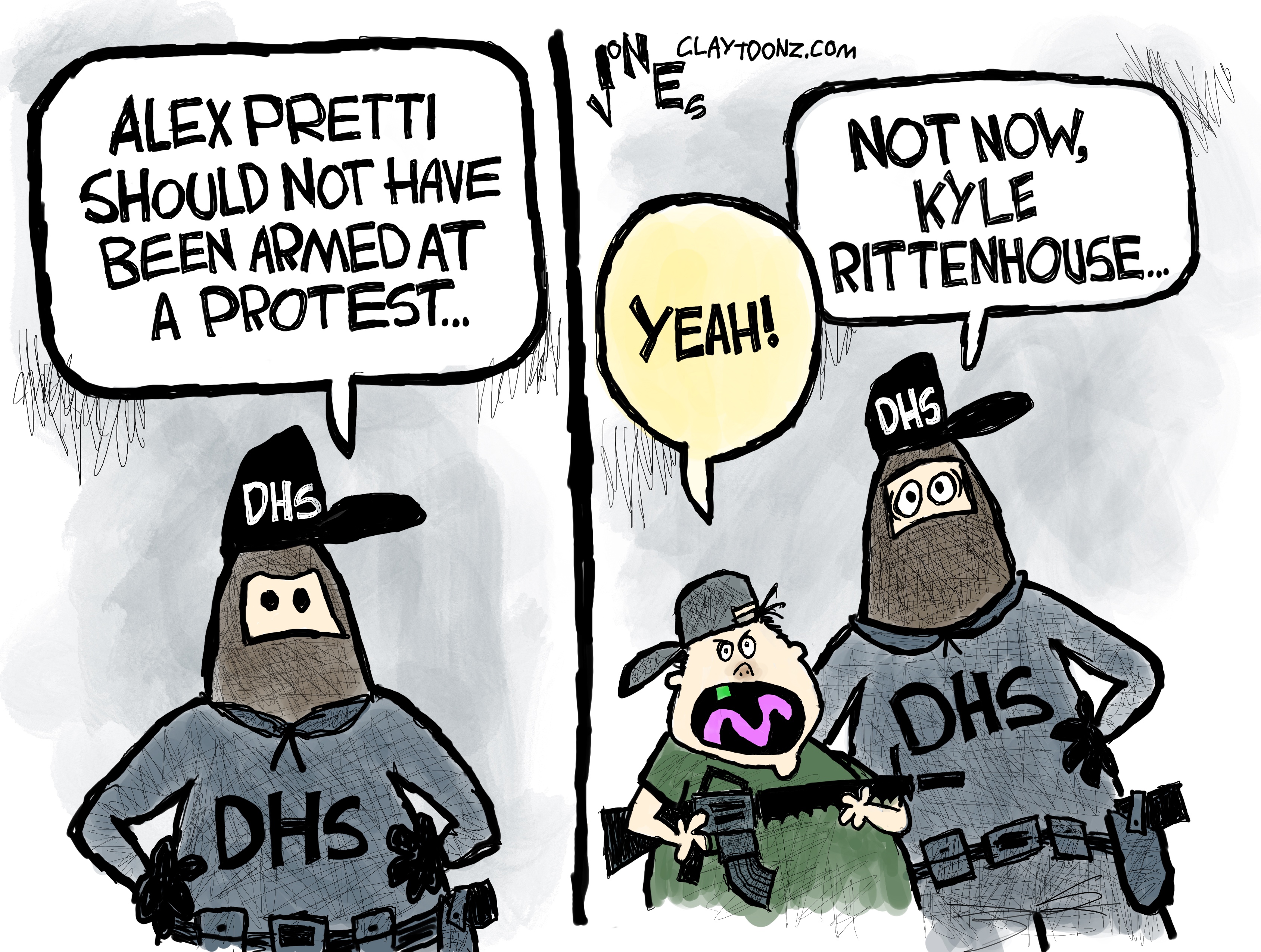

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities