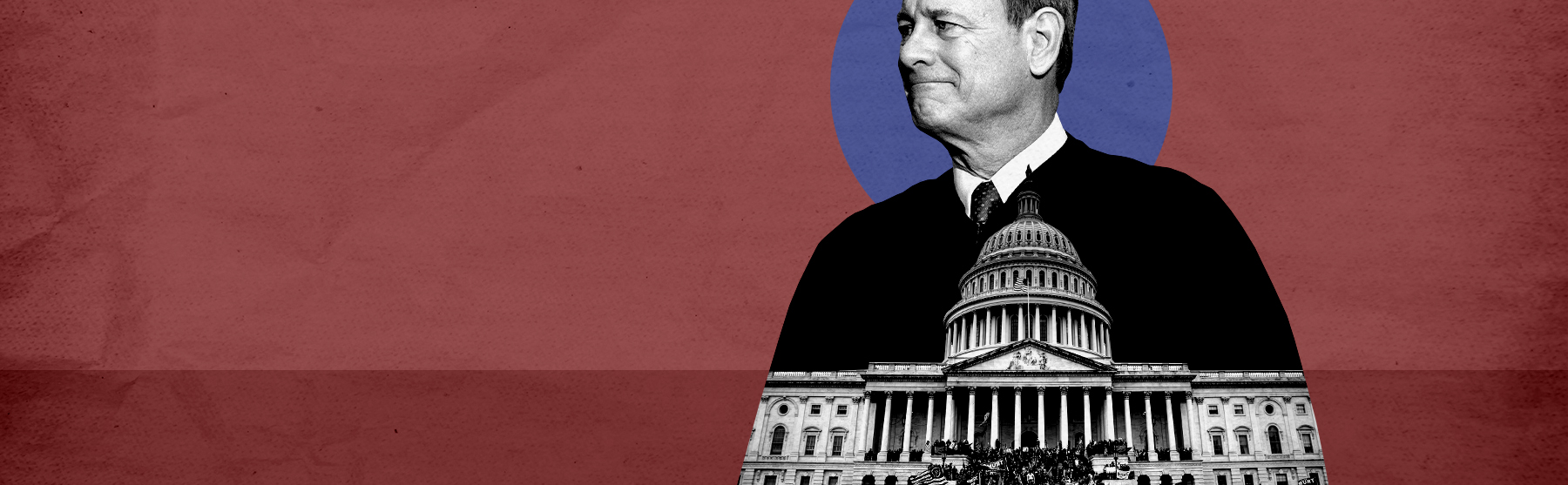

The most important person in the impeachment trial is missing. It isn't Trump.

Why John Roberts' refusal to preside is more significant than many have acknowledged

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For more than two hours on Wednesday afternoon the senators at Donald Trump's second impeachment trial were addressed by a congressman best known for farting on live television and falling for a Chinese honey trap.

Why Democrats would choose Rep. Eric Swalwell to help present their case is a question for Mr. Owl. His role is a perfect illustration of what makes these proceedings so tedious. We are solemnly assured that the trial is the most important thing happening in the world, yet nothing of interest can be said about it. The participants on either side are engaged in a rote mechanical exercise; the outcome is not remotely in doubt.

Two persons who will not be appearing at the trial could have made it a more memorable affair. One of them is the accused himself, whose testimony would at least have been entertaining. The other is Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, whose refusal to preside is more significant than many observers have acknowledged.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As law professor Gregory Mark has pointed out, the Chief Justice's absence not only provides the former president with a specific and at least somewhat plausible legal remedy in the unlikely event that he is not acquitted; if Trump chose to run for office again after being convicted, it would also put the Supreme Court in a very uncomfortable position. "The fates lead the willing and drag the unwilling."

Ever since United States v. Nixon, the high court has made it clear that it considers impeachment a purely political matter that is beyond the purview of its authority. In theory, a conviction by the Senate would not be subject to any kind of legal challenge, much less adjudication by Roberts and his fellow justices.

But if Trump were convicted in this case, he and his lawyers would almost certainly argue that the trial was unconstitutional precisely because Roberts did not preside, directly in contradiction of the plain words of the text, rendering the judgement and the penalty of disqualification from office void. I, for one, am less interested in whether this is a compelling argument than I am in the fact that in what Democrats consider an ideal outcome it would almost certainly be made and would thus require an answer. The precise legal mechanism that would signal such a challenge — the refusal of the Federal Election Commission to file paperwork on behalf of his presidential campaign, a primary ballot access lawsuit — does not matter. Sooner or later, probably long before any actual voting, the courts would have to rule on the question of whether the Senate trial was conducted in a legitimate manner.

I cannot begin to guess how the Supreme Court would rule in such a case (with the exception of Roberts, who would obviously recuse himself). I also suspect that the justices would do almost anything to prevent themselves from having to rule one way or the other. If it had appeared possible even for a moment last month that Democrats were close to the 67 necessary votes to convict Trump, making future Supreme Court litigation on impeachment a near certainty, would Roberts have made the same decision? I doubt it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why then did Roberts refuse to participate, creating a highly improbable but logically possible scenario in which Trump would be able to void a Senate conviction? It seems to me unlikely that the Chief Justice had some nefarious motive here. Rather than a sly attempt to preclude the possibility of Trump's conviction and disqualification from office, Robert's decision not to participate strikes me as a tacit rebuke of the process itself, an extra-legal ruling of sorts.

This is not as strange as it might sound. Roberts, whom Trump criticized repeatedly, is probably as ready as millions of other Americans to put the last administration behind him. What he is not so subtly suggesting is that holding a second impeachment trial in as many years is a waste of his time and the country's. It is hard to disagree with the Chief Justice's verdict here.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not fired

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not firedSpeed Read Trump is publicly defending the Homeland Security secretary

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

Trump fears impeachment if GOP loses midterms

Trump fears impeachment if GOP loses midtermsSpeed Read ‘You got to win the midterms,’ the president said

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Democrat files to impeach RFK Jr.

Democrat files to impeach RFK Jr.Speed Read Rep. Haley Stevens filed articles of impeachment against Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

-

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’Feature Activists say a Supreme Court ruling has given federal agents a green light to racially profile Latinos