The case against packing the court

Democrats want to remake the Supreme Court in the worst way

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The main problem with "court packing" is that it won't work.

If Democrats were to succeed in adding members to the Supreme Court in order to tilt its ideological balance to liberals, Republicans will just tilt it back the next time they (inevitably) regain power by appointing even more conservative justices. Any new precedents created by a left-leaning court would be reversed the next time conservatives added seats. The ensuing battles would probably drain the high court of the support and respect it still commands from the American public.

There are few long-term victories for Democrats to gain from such a project, in other words, and plenty of pitfalls.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet packing the court remains popular, even imperative, among the party's activist base. That is why President Biden last week created a commission that will examine reforms both to the Supreme Court and the broader federal judiciary. (The commission will examine "the membership and size" of the high court.) Given Biden's well-known skepticism of court packing, the commission's birth might be a maneuver to keep his party's base at bay for the moment — but it could also be the first step toward big changes to the court.

Those changes would be welcomed by progressives who blame Republicans for creating a crisis on the court.

E.J. Dionne, a Washington Post columnist, recently summed up the pro-packing case this way: "The Supreme Court faces a legitimacy crisis not because progressives are complaining but because of what they are complaining about: a reckless, right-wing, anti-democratic court majority, and a conservative court-packing campaign marked by the disgraceful Republican blockade against President Barack Obama's nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016 and the unseemly rush to confirm Justice Amy Coney Barrett just before President Donald Trump's defeat last November."

This leads to the second, more imminent problem with court packing: It's not clear that American voters share Democrats' sense of grievance.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Though a commonplace notion among progressives, it might be wise to be skeptical of any proclamations that the court has lost legitimacy. Gallup polling over the last 20 years shows the Supreme Court's popularity has ebbed and flowed — but generally, more Americans have approved than disapproved of the job justices are doing. Another poll indicated that Republican support for the court dropped drastically in December, when justices refused to take up Texas' lawsuit challenging Joe Biden's presidential victory. Even then, in the wake of Barrett's confirmation, 43 percent of Americans approved of the Supreme Court's performance — while just 35 percent disapproved. That admittedly is not the widest of margins, but it's not all that bad in our era of political polarization. In most polls, the Supreme Court is usually more popular than the White House or Congress.

The public, it seems, is not crying out for reform.

Nor is the Democratic Party in lockstep agreement. In addition to Biden's caution on the issue, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has declared himself against court packing — which means Senate approval in the 50-50 chamber would be tough to achieve. (And don't forget that Republicans would certainly filibuster any bill adding seats to the court.) Even Justice Stephen Breyer, one of the court's last remaining liberal justices, last week announced his opposition to the idea.

"If the public sees judges as 'politicians in robes,' its confidence in the courts, and in the rule of law itself, can only diminish, diminishing the court's power, including its power to act as a 'check' on the other branches," Breyer said in a speech at Harvard Law School.

If packing advocates overstate the court's legitimacy crisis, Breyer probably underplays how much the court is already seen as a political institution. The Supreme Court doesn't always deliver on partisan goals; Trump might still be president if that were the case. But the fierce confirmation battles of recent decades, pitting Republicans against Democrats in ever-more-heated clashes, have given the public ample reason to believe that politics do permeate its business. Still, Americans and their elected officials continue to obey the court's rulings and adhere to its precedents. That's the ultimate form of legitimacy.

None of this is to say that progressives should be satisfied with the court's rightward turn. For the moment, however, there may not be much that can be done about it. Democrats need to convince the public — and more of their own elected officials — that big changes are needed. Unless that happens, court packing is just a pipe dream.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’Feature Activists say a Supreme Court ruling has given federal agents a green light to racially profile Latinos

-

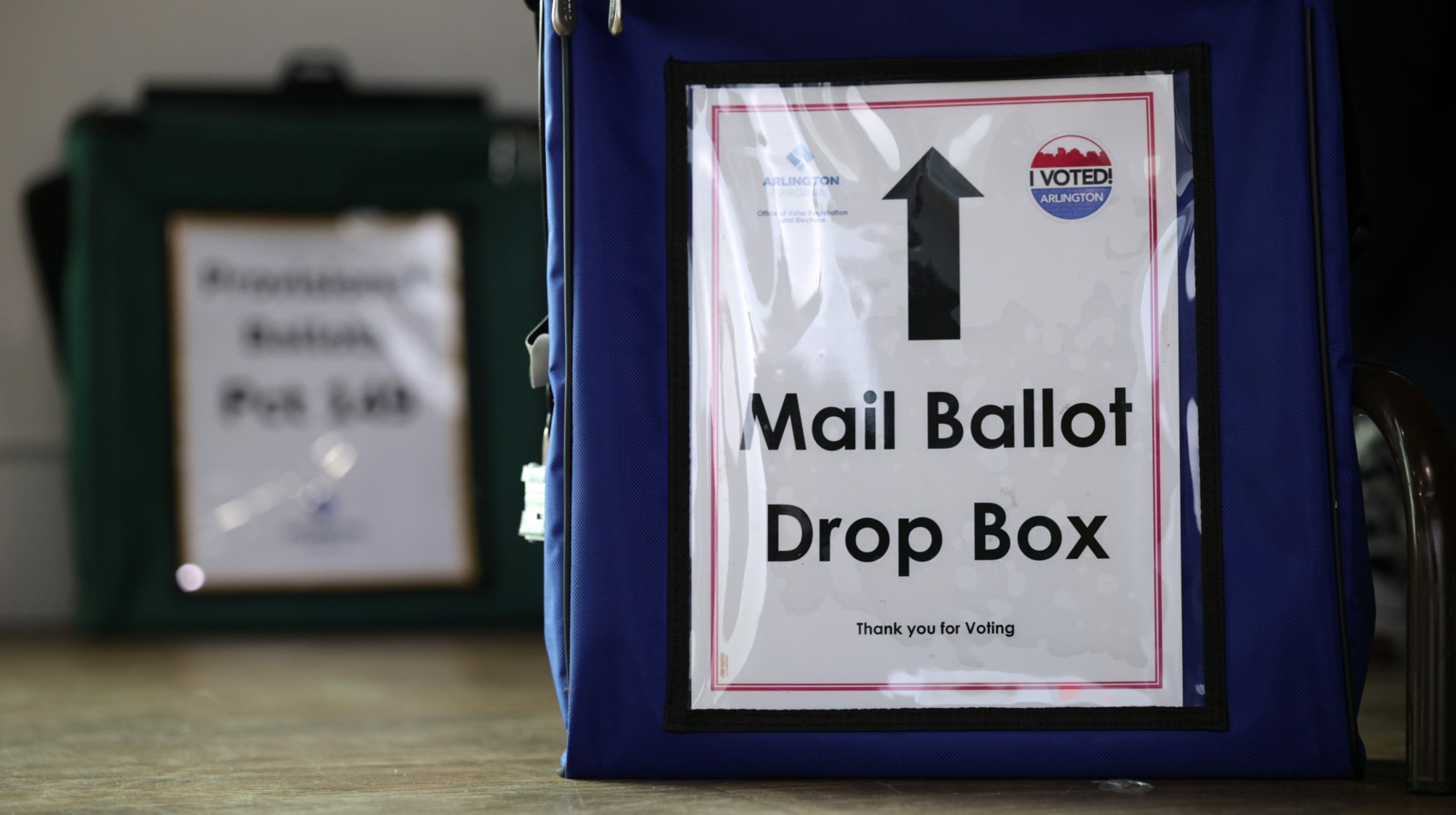

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limits

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limitsSpeed Read The court will determine whether states can count mail-in ballots received after Election Day

-

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme Court

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme CourtSpeed Read Even some of the Court’s conservative justices appeared skeptical

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party