Francis Bacon: Man and Beast at the Royal Academy – what the critics say

Show brings together several dozen paintings done over the course of Bacon’s 50-year career

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Francis Bacon was “obsessed with the animal world”, said Rachel Campbell-Johnston in The Times. Brought up the son of a racehorse trainer in Ireland, the child who would become “Britain’s most important postwar painter” was a “sickly asthmatic” with an allergy to dogs, and no interest in country pursuits: he “preferred prancing around in girls’ knickers to shooting or riding with hounds”.

Yet all his life, Bacon (1909- 1992) observed animals closely, and as an artist he sought to capture “the unvarnished reality of our human condition” by observing their “uninhibited behaviour”. He watched wild animals in Africa, drew inspiration from the photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s images of animals in motion, and was “riveted” by the primates at London Zoo.

This new exhibition is the first to explore this theme, demonstrating how his interest in animals “at once shaped and warped his approach” to painting the human body. The show brings together several dozen paintings Bacon realised over the course of his 50-year career, from hesitant early works to his final canvas, a “long-lost” depiction of a bull painted in 1991, the year before his death. The “nightmarish menagerie” it presents is harrowing from start to finish – yet, often enough, it is also “profoundly moving”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There’s “much to admire” here, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. The first image we encounter is a “grisly” painting depicting a “fanged chimpanzee’s mouth, frozen in a howl”: we could be looking straight into “the jaws of hell”. The main draw is a series of privately-owned paintings that have seldom been seen in public, such as Two Figures (1953), depicting a pair of men wrestling “atop bedsheets as luscious as Chantilly cream”. Known as “The Buggers”, it hung in Lucian Freud’s bedroom until he died.

Yet the exhibition is hardly breaking new ground. The idea that the central thrust of Bacon’s work was to demonstrate “the bestiality of mankind” is rather obvious, while several paintings here appear to derive little, if anything, from his observations of animals. What’s more, though Bacon’s paintings may have been “urgent and courageous” expressions of nonconformity when he painted them, they are now “trophies for the super-rich” that seem a little “out of step” with the time – a little “histrionic”.

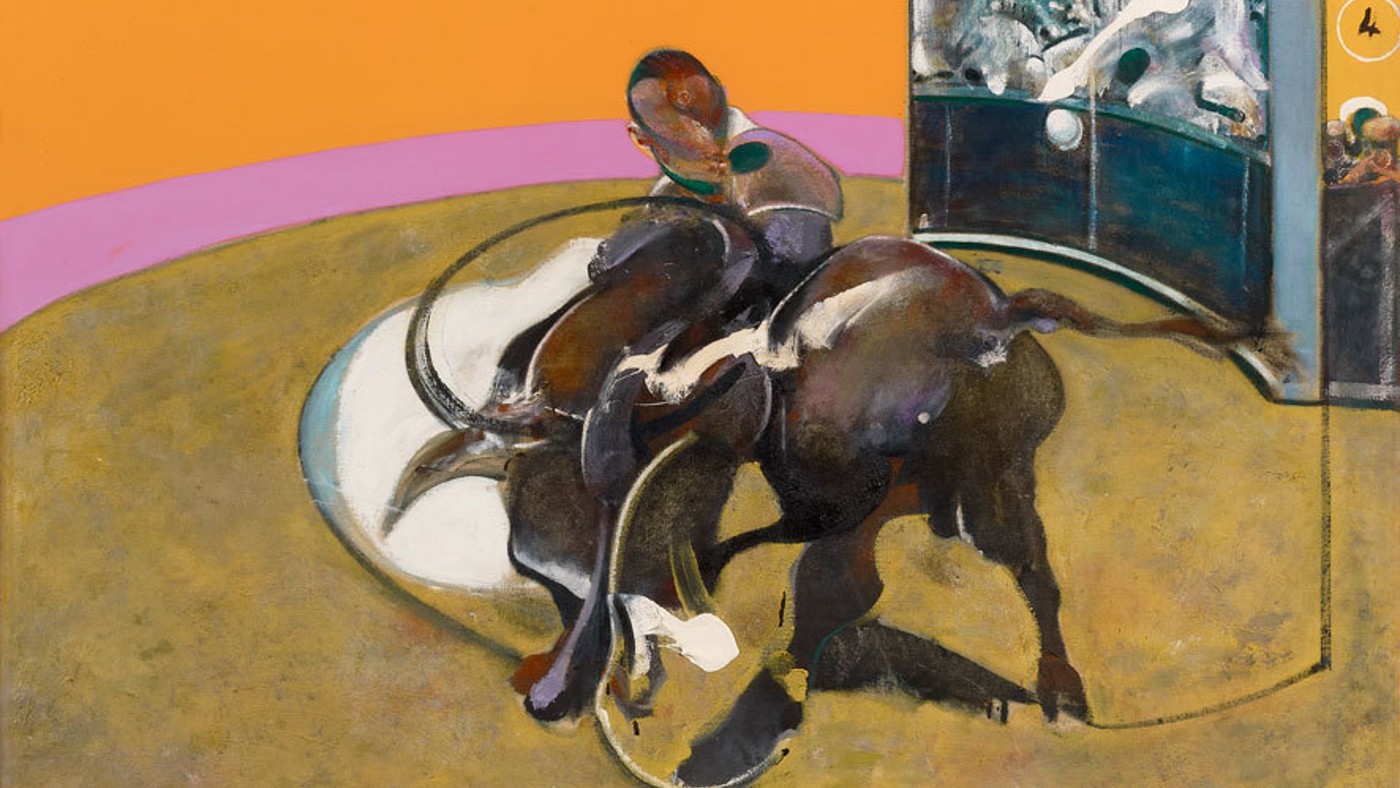

Bacon is “not always very good”, said Adrian Searle in The Guardian. An “absurd” depiction of his doomed lover George Dyer has its subject seated, his leg dissolving “like a puddle of Silly Putty”; his three paintings of bullfights, gathered together here for the first time, are somewhat melodramatic and “overcooked”; a study of two owls on a branch, meanwhile, just isn’t up to much.

Nevertheless, he is always “arresting”, and there are some wonderful works in this exhibition: one of his screaming popes, with the pontiff in “cloistered solitude, gasping for air”; or 1961’s Paralytic Child Walking on All Fours, a “genuinely shocking” image showing a contorted, simian figure advancing with menace. In Bacon’s work, familiar objects – “a plainly painted doorknob” or a piece of furniture–give way to nightmarishly surreal imagery: “vulnerable and distorted” bodies, screaming heads, “twisted physiognomies”. It’s monstrous: “I want to run away, I can’t stop looking.” And it all adds up to a “grim” but “endlessly fascinating” show.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Royal Academy, London W1 (royalacademy.org.uk). Until 17 April