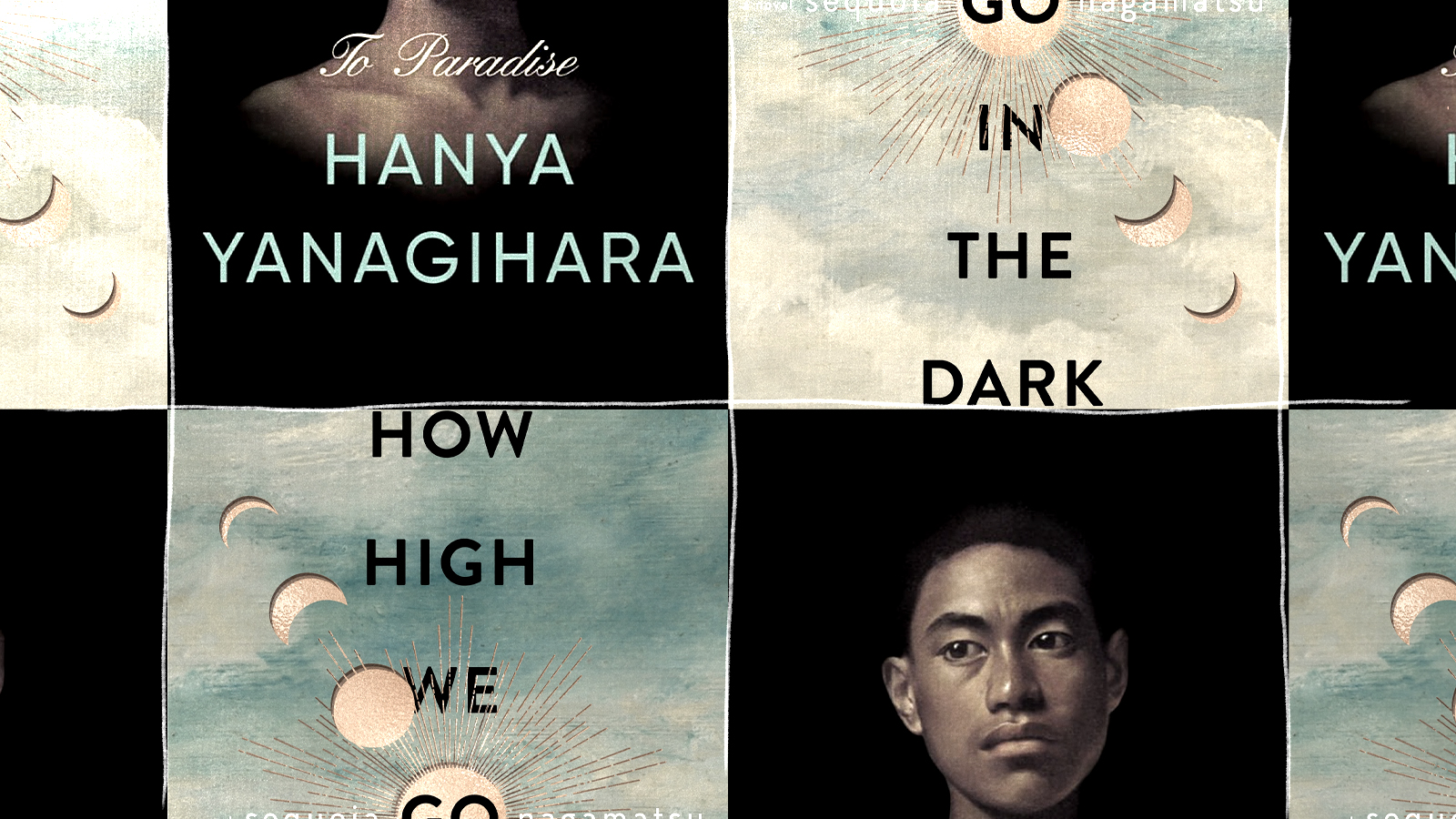

The muddle and mastery of To Paradise and How High We Go in the Dark

Two expansive new books share a similar construct. But the similarities end there.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Hanya Yanagihara's highly anticipated To Paradise and Sequoia Nagamatsu's debut novel How High We Go in the Dark, both new this month, share a basic premise: hyperlinked stories, connected across hundreds of years. But the books' differences are ultimately far more vast than their similarities: To Paradise is bloated, in love with its own self-importance, and squanders a fairly promising premise after its first 177 pages. Nagamatsu's novel, however, is a small, slim gem, one that I will likely return to for the rest of my life.

How High We Go in the Dark begins with Dr. Cliff Miyashiro, a professor of archeology and evolutionary genetics at UCLA, who has traveled to Siberia in order to finish his late daughter's research of microbes emerging from the tundra. Clara, his daughter, was found in a cavern, having fallen through thin ice, and her study of a perfectly preserved corpse, a young girl, found in a cave nearby, was thus interrupted. The team in Siberia has already found, and is in the process of reanimating, "well-preserved giant viruses [they've] never seen before." As you might imagine, this goes badly.

The not-so-hypothetical premise results in two memorably gut-wrenching chapters. In "Pig Son," David, a research scientist, harvests organs from pigs in order to save infected children from the Arctic plague. Donor 28, a.k.a. Snortorious P.I.G. begins to speak. In English. In their wonder, the scientists immediately begin to treat Snortorious as a human child:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"He seems to soak up everything we share with him — flashcards, cartoons, children's books. … Mornings and evenings, he screams the word hungry. … He favors reruns of the old Crocodile Hunter show on Animal Planet, snorting excitedly whenever he sees a hippo. … He has begun … asking the big questions, like why are we all here? … He asks about people in Washington fighting over a moratorium on gas automobile production … He asks What is a moratorium? … Many sick people. Nobody agree on anything."

Unfortunately, the university learns of Snortorious' abilities. I don't want to give away what happens next. This chapter is painful, but the love, respect, and admiration in it are just as stunning as the pain.

In another chapter, "City of Laughter," an eponymous theme park is built on (it is implied) the abandoned grounds of Alcatraz Prison. Terminally ill children come to the park with their parents and spend the day riding on rollercoaster after rollercoaster. Just before the last ride, the child is given a drink that lulls them into unconsciousness, and by the time the ride ends, they're dead. I read this chapter at around 11 p.m. one night and was unable to sleep until about midnight the next day.

To Paradise is also broken into sections; in this case, it is three separate books bound as one. The first book navigates a kind of queering of Henry James' milieu. David Bingham, older brother to Eden and John, lives in a Washington Square townhouse with wealthy Grandfather Nathaniel. Eden and John are in same-sex marriages, which are legal in the "Free States." David meets Edward Bishop, a charming, penniless rogue. Their love affair is shattered only by Grandfather Bingham's private investigator, whose report on Edward's life exposes his trove of lies. In response, David permanently leaves his family. We learn nothing about him after he departs for the West with Edward.

What comes next are two separate books, skipping ahead from 1893 to 1993, and again to 2093. Both are dismal. The second book, though, is particularly stomach-turning, a first-person narrative from the point of view of David's father, who is dying of an undisclosed illness in Hawaii. David's father is the rightful king of Hawaii (confusingly, he is named both Kawika and David, as is his son). Though many characters in literature are weak, Yanagihara uses the father's weakness as an explanation for his abusive relationship with his son. The father's justification for his continued complacency in sacrificing his and his son's life — he traps his son on the island, where they sleep under a tarp on the sand — for "that play" is apparently supposed to elicit sympathy in the reader. It does not:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"I knew that what I was doing was wrong. So why did I let it happen? How could I let it happen? The truth is … pathetic. The truth is that I had simply followed someone, and I had surrendered my own life to somebody else. Once I had done so, I didn't know how to fix what I had done, [or] how to make it right."

It's difficult to tell who has more contempt for Kawika: me, or Yanagihara.

The third book of To Paradise is split: half told in letters from yet another Charles, a government scientist, to a friend, starting in 2045. The other half is told in first person by Charlie, Charles's granddaughter, in 2093. The elder Charles, in 2045, has moved husband Nathaniel and son David from Hawaii to New York City so he can work at Rockefeller University, where he spends his days "dreading a new outbreak, but [yearning] for one as well." This is a particularly obscene character motivation, especially when read in the midst of our own ever-deadly plague.

In contrast to Yanagihara's tone-deafness, How High We Go in the Dark effectively uses humor to humanize the story. The Arctic plague gives rise to droves of new industries, including elegy hotels, which will sterilize, embalm, and antibacterially plasticize your loved one, so you can sit with their preserved mannequin in a hotel room, ordering food, lighting incense, etc. The dead will then be cremated and the urn returned to you. The ad copy for the hotels is hilarious:

"Send off your loved ones in our luxury suites! Say goodbye to morgues and cold storage and hello to a 3 1/2 Star Resort Treatment! Low Interest Payment Plans Available!"

How High We Go in the Dark chooses to transcend the chaos and anguish of our pandemic lives, while Yanagihara chooses to languish in the self-importance of her own writing. A recent New Yorker profile of the author was titled "Yanagihara's Audience of One." This makes sense: I can easily imagine Yanagihara wrote the book to please herself. Nagamatsu, on the other hand, wrote this book to give us, in the tedium of fear and despair, a rare moment of wonder.

Nandini Balial is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New Republic, Vice, Slate, Wired, The Texas Observer, and Lit Hub, among others. She reluctantly lives in Fort Worth, Texas.