A big bet on Amtrak

The bipartisan infrastructure bill could revitalize interstate rail travel in the U.S. But will Americans embrace trains?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The bipartisan infrastructure bill could revitalize interstate rail travel in the U.S. But will Americans embrace trains? Here's everything you need to know:

How much will Amtrak get?

The $1 trillion bill provides the quasi-public rail corporation with a $66 billion cash infusion — a massive increase in funding over the $2 billion it currently gets in federal subsidies a year. The new cash will enable the beleaguered passenger-rail operator to improve nationwide service while expanding to new cities. The bill directs $24 billion in funding to the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak's most popular and heavily used line, which connects Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington with trains reaching up to 150 miles per hour. The bill also dedicates $22 billion to the existing national network, which will provide better service to such high-traffic routes as Chicago-Milwaukee and Portland-Seattle, and $12 billion to new rail services, which Amtrak plans to use to expand to smaller cities like Boise, Idaho; Madison, Wisconsin; Nashville; and President Biden's hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania. The president, who famously commuted by Amtrak from Delaware to D.C. while serving in the Senate, called the funding a "once-in-a-generation opportunity" to make rail a crucial part of America's transportation future. "We can make investments that get America back on track, no pun intended," Biden said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did rail service get off track?

It was a casualty of America's car culture. In the 19th century, the U.S. pioneered rail travel to speed people and goods across a vast continent. By the 1850s, passenger rail service was booming, drastically reducing intercity travel times and opening the West to large-scale settlement. But by the 1920s, the number of rail passengers began to plummet as more Americans became automobile owners. That trend accelerated after World War II, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act, which funded the grid of cross-country high-speed roads that became the modern interstate system. Passenger rail would never be the same.

Why has Amtrak struggled?

Amtrak was created in 1971 by combining several failing private passenger-rail networks into a for-profit company receiving government subsidies. To the never-ending frustration of Republican lawmakers, Amtrak has never made a profit; to the frustration of Democrats, it has always received drastically less funding than the interstate highway system. Amtrak has been plagued by slow service due to decades-old infrastructure: The actual average speed of the Northeast Corridor's Acela trains is just 84 mph, compared with 180 mph or more for high-speed lines in Europe and Asia. In much of the U.S., tracks are owned by more-profitable freight-train companies, which get priority use. The nation's only high-speed project, which was supposed to connect San Francisco and Los Angeles, has become a much-delayed, vastly overbudgeted boondoggle that would cost $23 billion to go just 171 miles from Merced to Bakersville. It is not mentioned in the infrastructure bill.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are trains successful abroad?

High-speed rail is ubiquitous in Japan, Taiwan, and much of Europe, where distances between cities are shorter and governments see rail as a public service to be subsidized, rather than a for-profit business. China has blanketed its sprawling country with 23,500 miles of high-speed lines connecting every major urban center, including far-flung western cities. Its centralized government does not need to overcome public opposition to construction or heavy state investment. And in China, the per-mile cost to build high-speed rail is less than half of California's.

Why are train projects so expensive?

It's not just the trains: America's highways, roads, bridges, and tunnels also cost many billions to build, for a host of complex reasons. The conventional wisdom is that American unions and high labor costs are the cause, but research by economists and transit researcher Alon Levy of the libertarian Niskanen Center point to other factors: bureaucratic mismanagement by officials who know little about rail or construction; environmental laws requiring "impact statements" that take an average of 4.5 years to complete; and not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) lawsuits by residents and wealthy interests. "Once the construction process starts, people complain," New York University professor and transit researcher Eric Goldwyn told Vox. "And those complaints lead to lawsuits." One study found that the cost to build a mile of highway grew by 500 percent between 1990 and 2008. Building a new subway line on Second Avenue in New York City cost $2.6 billion per mile. Rail advocates hope Amtrak will learn from Europe, where more-experienced planning agencies have streamlined processes to handle citizen complaints and environmental reviews.

How will Amtrak use the money?

Don't expect the U.S. to develop a high-speed rail system like Europe's or China's. It's simply not practical. The money will primarily go into repairing and upgrading Amtrak's existing rail network, and in creating new routes to cities with existing freight lines. The hope is that if service becomes faster, more reliable, and more far-reaching, Americans tired of jam-packed highways and the hassles and delays of air travel will give trains a try — and become repeat customers. The infrastructure bill gives Amtrak a significant new mandate: It will not be expected to make a profit. Instead, it will be a taxpayer-supported service to "meet the intercity passenger rail needs of the United States."

Buttigieg's big challenge

Pete Buttigieg, President Biden's transportation secretary and a former Democratic presidential candidate, will be responsible for managing at least $105 billion of the bipartisan infrastructure bill's new spending. That's "way more than any other" transportation secretary has ever been given, said Jeff Davis of the Eno Center for Transportation. It also creates a major test for Buttigieg, whose most recent budget as mayor of South Bend, Indiana, was just over $350 million. Buttigieg, who is widely expected to run for president again in the future, has been given the chance to be the face of a new era of American infrastructure. "The biggest threat to American competitiveness is continuing to believe that we can have a world-leading economy with third-rate infrastructure," Buttigieg said. As a result of the new funding bill, he said, "there is no county, no community, certainly no state in this nation that won't see improvements."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Ports reopen after dockworkers halt strike

Ports reopen after dockworkers halt strikeSpeed Read The 36 ports that closed this week, from Maine to Texas, will start reopening today

-

The rise of the world's first trillionaire

The rise of the world's first trillionairein depth When will it happen, and who will it be?

-

Would Trump's tariff proposals lift the US economy or break it?

Would Trump's tariff proposals lift the US economy or break it?Talking Points Economists say fees would raise prices for American families

-

Will college Gaza protests tip the US election?

Will college Gaza protests tip the US election?Talking Points Gaza protests on U.S. campuses pose problems for Biden like the ones that hurt Lyndon B. Johnson in the '60s

-

Can Trump get a fair trial?

Can Trump get a fair trial?Talking Points Donald Trump says he can't get a fair trial in heavily Democratic Manhattan as his hush money case starts

-

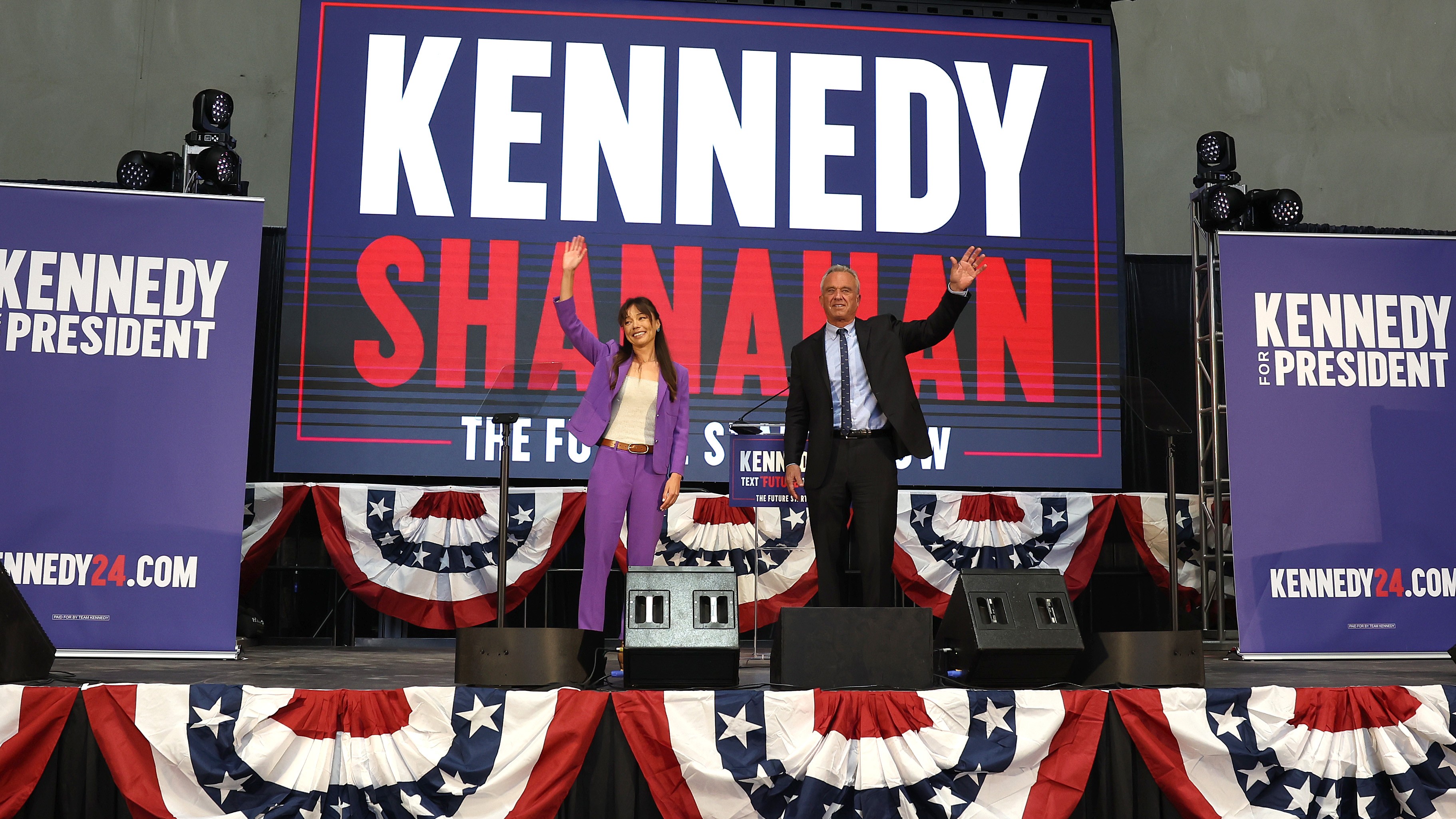

What RFK Jr.'s running mate pick says about his candidacy

What RFK Jr.'s running mate pick says about his candidacyTalking Points Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s' running mate brings money and pro-abortion-rights cred to his longshot presidential bid

-

Housing costs: the root of US economic malaise?

Housing costs: the root of US economic malaise?speed read Many voters are troubled by the housing affordability crisis

-

Did the Biden impeachment inquiry just collapse?

Did the Biden impeachment inquiry just collapse?Talking Points Key GOP impeachment inquiry witness Alexander Smirnov says Russian intelligence fed him lies