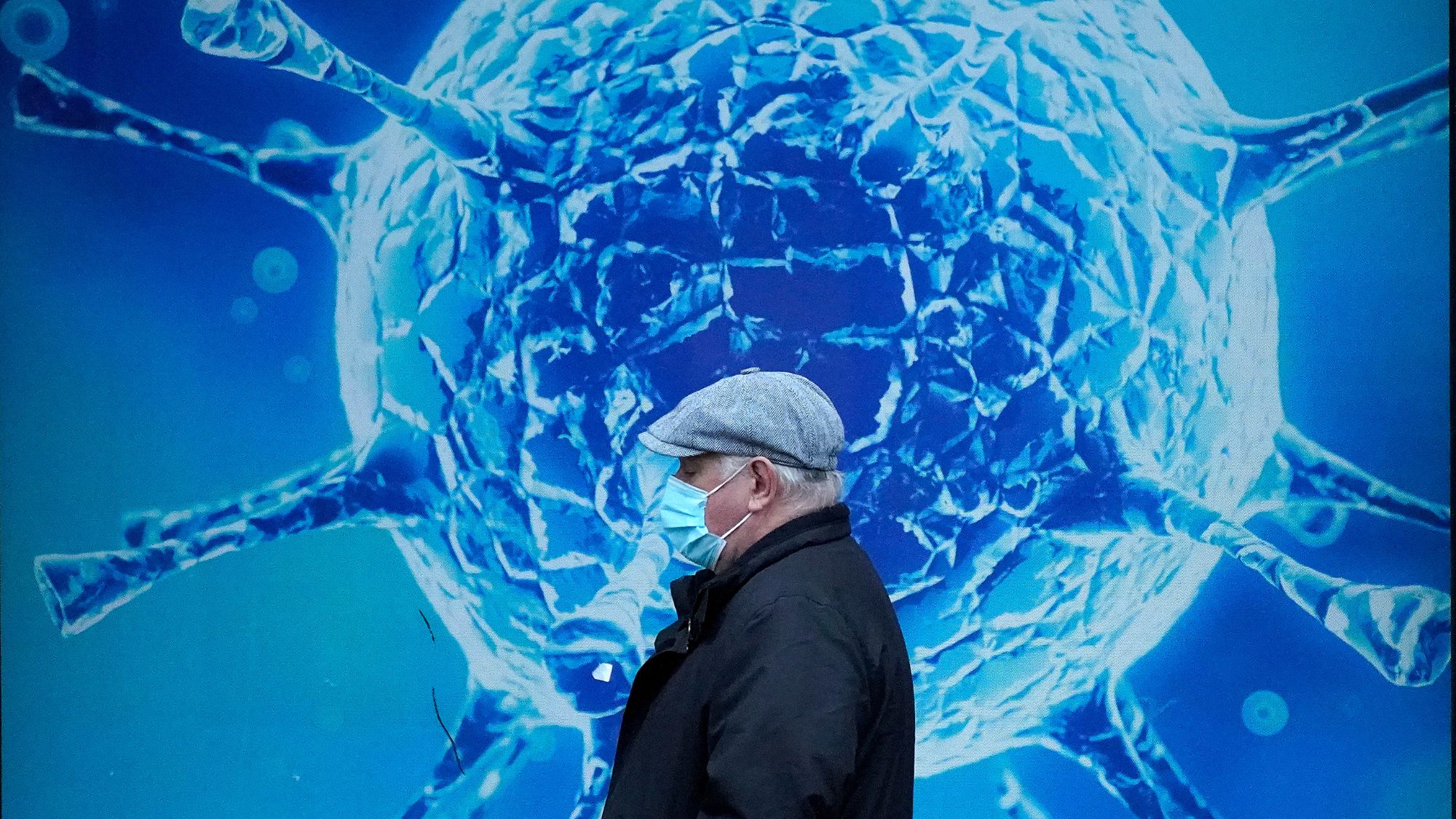

The new coronavirus research out this week: vaccines and immunity

A weekly digest of the latest data and scientific studies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As soon as a new coronavirus was identified in China at the end of last year, the world’s scientists set about investigating the threat it posed.

Each week we bring you a round-up of the progress they’ve made in understanding the spread of Covid-19 – and developing the vaccines, treatments and preventative measures that will bring it under control.

Vaccine progress

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Arguably the most encouraging development this week was news that Oxford University researchers are to start testing a potential Covid-19 vaccine on more than 6,000 volunteers by the end of this month.

“Scientists at the university’s Jenner Institute had a head start” in the global race to find the magic bullet, “having proved in previous trials that similar inoculations - including one last year against an earlier coronavirus - were harmless to humans”, The New York Times reports.

As a result of that earlier success, UK regulators have agreed an accelerated approval process, which means “the first few million doses of their vaccine could be available by September… if it proves to be effective”, says the US newspaper. That is a big if (see below), but small-scale research involving primates has proved encouraging: six rhesus macaque monkeys given the Oxford team’s vaccine in US tests remained healthy despite being exposed to a large dose of Covid-19 that infected a control group of the same species.

Assessing antibodies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the absence of a vaccine, humans have to rely on the antibodies that their bodies produce naturally once infected with the Covid-19 cononavirus. How long those antibodies last, and how effectively they protect us, will help to determine how quickly normality can return.

A newly published paper in The Lancet attempts to answer those questions, but warns that scientists still have too little data to make firm predictions about the virus now causing misery worldwide. “The best estimate comes from the closely related coronaviruses and suggests that, in people who had an antibody response, immunity might wane, but is detectable beyond one year after hospitalisation,” the authors write.

A year’s worth of immunity might protect people from re-infection during the current outbreak, but this may be “of little reassurance given the possibility that there could be another wave of Covid-19 cases in three or four years”, the paper says.

If we are lucky, however, the new coronavirus may be more like the one that caused Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers) in 2015. Patients who recovered from that disease still had some immunity four years later.

Are the kids really all right?

Researchers investigating the role of children in spreading Covid-19 have published apparently contradictory conclusions this week. Christian Drosten, director of the Institute of Virology at Berlin’s Charite Hospital, released a paper that “suggested children could be as infectious as adults”, and cautioned against reopening schools, reports The Guardian.

But “the Swiss government said grandparents are now allowed to hug their grandchildren”, according to Sky News, which reports that a new review of 78 studies from around the world “found there has not been a single case of a child under ten transmitting Covid-19”.

The review was overseen by children’s health blog Don’t Forget the Bubbles, in partnership with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and concluded that young people “do not play a significant role” in transmission.

Review leader Alasdair Munro, a clinical research fellow in paediatric infectious diseases, says that some reports have overstated his team’s conclusions, but also questioned the methodology of the German study.

“While we don’t know for sure”, there is growing evidence that “children are less susceptible to infection, have milder infection, and are infrequently responsible for household transmission”, Munro tweeted.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variants

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variantsin depth Rapidly spreading new JN.1 strain is 'yet another reminder that the pandemic is far from over'

-

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid science

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid scienceSpeed Read Then PM struggled to get his head around key terms and stats, chief scientific advisor claims

-

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023In Depth A fingerprint test for cancer, a menopause patch and the shocking impacts of body odour are just a few of the developments made this year

-

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?feature The so-called Kraken strain can bind more tightly to ‘the doors the virus uses to enter our cells’

-

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?Today's Big Question The jab combines the original form of the Covid vaccine with a version tailored for Omicron

-

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?feature Notoriously secretive state ‘on verge of catastrophe’

-

Did Sweden’s Covid-19 experiment pay off in the end?

Did Sweden’s Covid-19 experiment pay off in the end?In Depth Scandinavian country had lower excess death rate than many but immigrants and elderly bore the brunt