Which is kinder? A firing squad or the electric chair?

There's no good way to kill a prisoner. That won't stop South Carolina.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

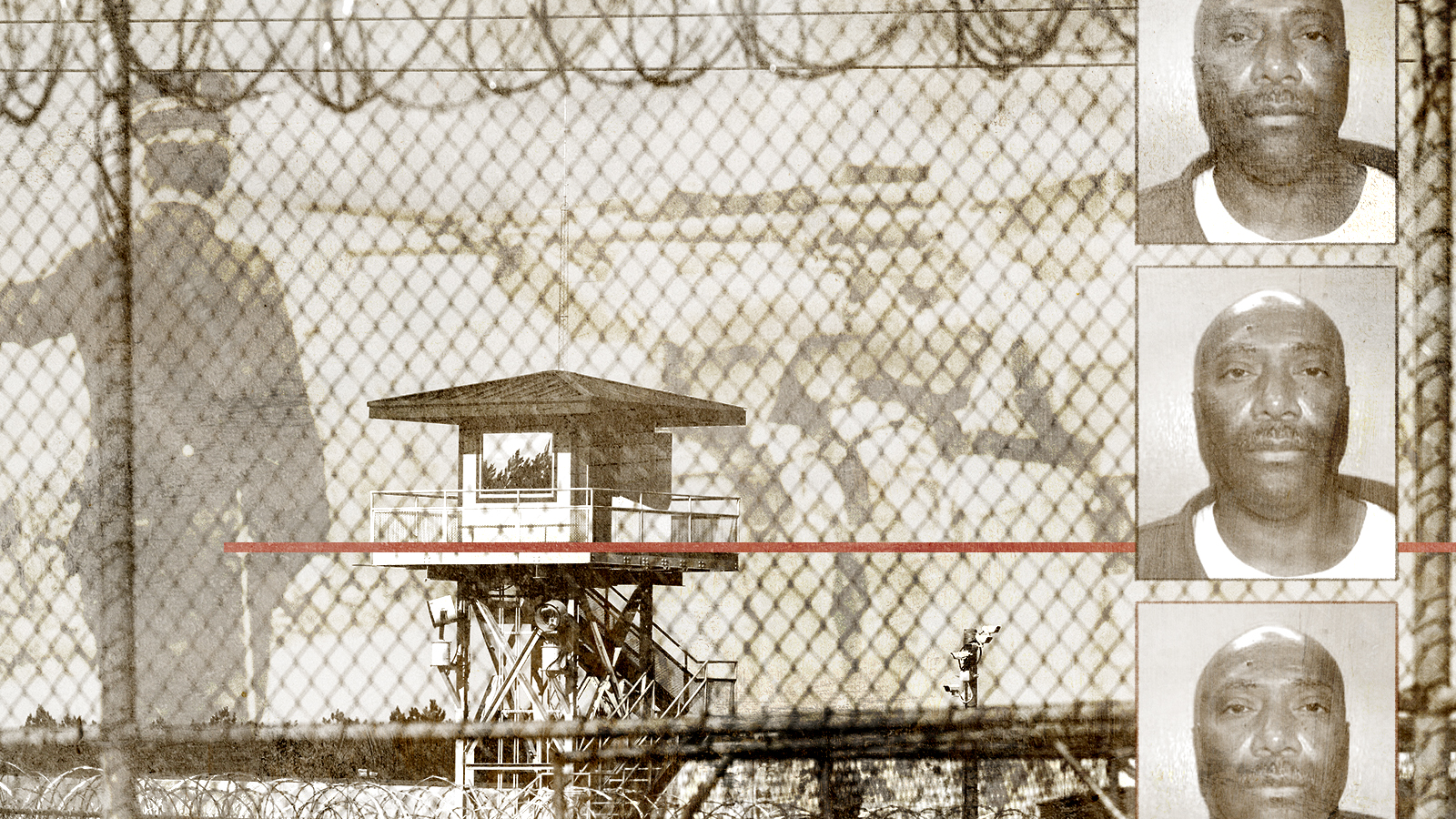

Before the end of the month, South Carolina is scheduled to execute Richard Bernard Moore for the crime of murdering a convenience store clerk in 2001. The plan is that he will either be electrocuted or shot to death by a firing squad — the state leaves the option up to him. Understandably, Moore would prefer neither.

So Moore's attorneys have appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay of execution, citing the U.S. Constitution's prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment." "The electric chair and the firing squad are antiquated, barbaric methods of execution that virtually all American jurisdictions have left behind," Moore's attorney wrote in a court filing last week.

It would be a surprise if the high court rules in Moore's favor: Even before Justice Amy Coney Barrett gave conservatives a 6-3 supermajority on the bench, the Supreme Court routinely turned away death penalty appeals. And while executions in the United States are much more rare than they once were — the Death Penalty Information Center says there were 11 last year, down from 98 in 1999 — they're not exactly "unusual." Governments have been executing criminals and dissidents for as long as there have been governments, after all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But putting an otherwise healthy, living human being to death — no matter the method — is definitely cruel.

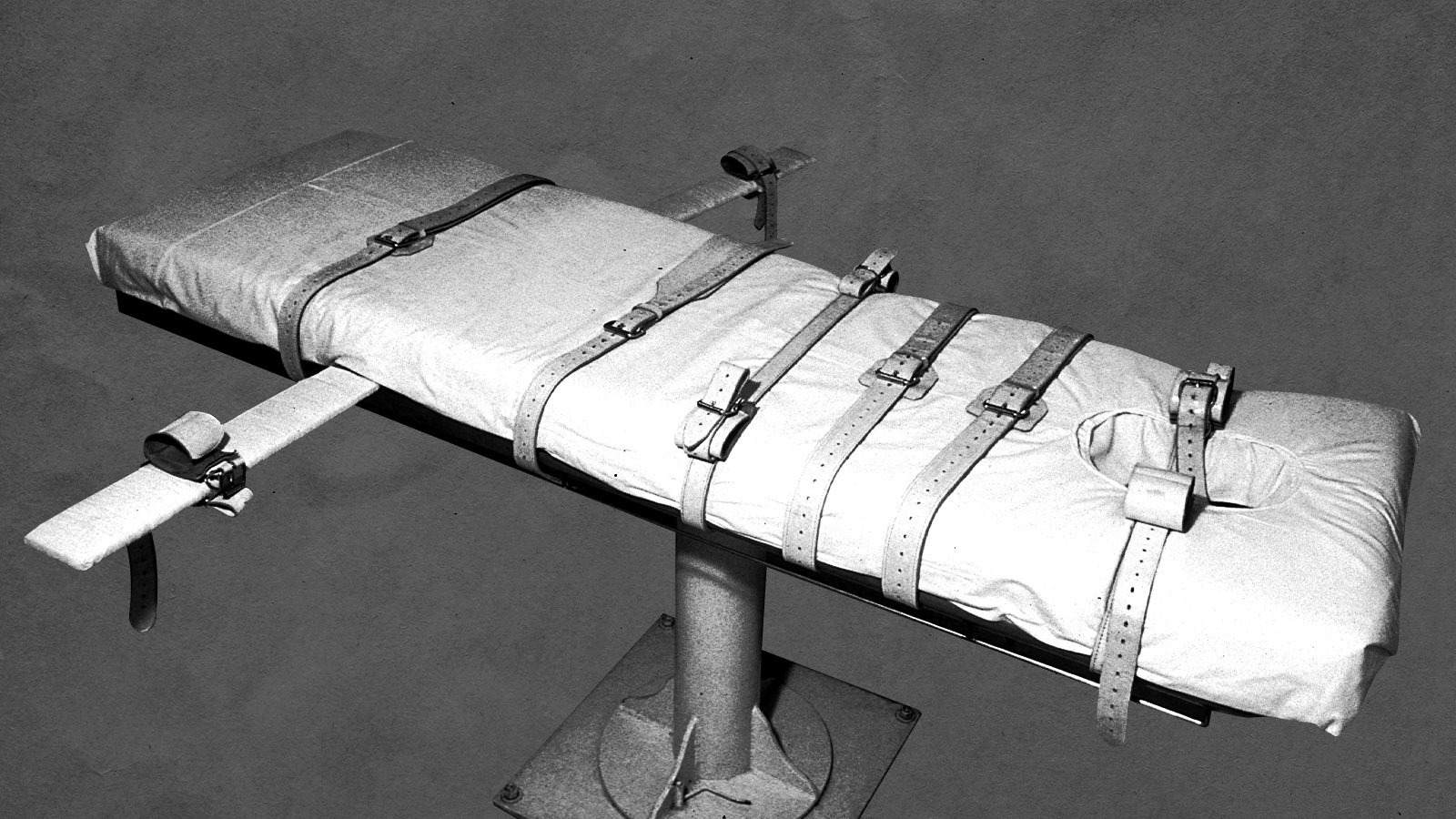

In South Carolina, Moore is being given the option of firing squad or electric chair because the state hasn't been able to secure the drugs for lethal injection for more than a decade. Strapping a prisoner to a gurney and pumping them full of chemicals once carried the sheen of being a humane method of executing prisoners — to observers, it often looked as though the inmate went to sleep and passed peacefully. But researchers have found that prisoners who undergo a lethal injection probably experience great suffering — we can't exactly ask them afterward — and there's evidence to suggest they're right: John Marion Grant vomited and convulsed during his 2021 execution in Oklahoma. Pharmaceutical companies have stopped selling the drugs to states, rather than take a public hit to their corporate reputation.

It's self-evident why any normal person should find the electric chair cruel: Indeed, some states that have the death penalty have already banned it as cruel and unusual. "Condemned prisoners must not be tortured to death, regardless of their crimes," the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled in 2008. Being shot to death in an execution chamber might reduce the amount and time of suffering, but the obvious violence of the act is why states have usually shied away from the method. "People think of lethal injection, and they think of a flu shot," Fordham law professor Deborah Denno told The Marshall Project. "It seems so violent to have a bullet go in you."

The question isn't whether these methods are cruel or not, then, but the degree of cruelty.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And that question doesn't just apply to the prisoners, but to the executioners. Despite measures used to keep any one person from bearing too much guilt for killing a prisoner — South Carolina will have three people on the firing squad, for example — "guards can feel mentally tortured by their participation in executions, both before and after," Robert T. Muller wrote at Psychology Today in 2018.

"The people who pass these bills, they don't have to do it," Jerry Givens, a former executioner for the state of Virginia, said in 2015. (The state banned the death penalty last year.) The people who do the executions, they're the ones who suffer through it." A system that inflicts such suffering on its own people is inherently cruel. Shouldn't that count, too?

None of this has anything to do with whether Richard Moore or any other convicted murderer deserves to die. The Constitution's "cruel and unusual" clause means prisoners retain a few rights, even if they have committed horrific acts.

And it's difficult to think that the death penalty, in this or any other case, serves much purpose beyond its cruelty.

Deterrence? There's little evidence the death penalty deters violent crime — and certainly not in the case of Moore, who didn't even carry a gun to his robbery. (He wrestled the weapon away from James Mahoney, the clerk, before shooting him.) Compensation for the crime? Moore's death won't bring Mahoney back to his family. There is nothing about Moore's death that will improve life in South Carolina.

The natural conclusion, then, is that the state's purpose is to make Moore feel the same terror and pain he inflicted on his victim. That's an understandable impulse, perhaps. It is also undeniably cruel.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

The countries around the world without jury trials

The countries around the world without jury trialsThe Explainer Legal systems in much of continental Europe and Asia do not rely on randomly selected members of the public

-

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBI

The Supreme Court case that could forge a new path to sue the FBIThe Explainer The case arose after the FBI admitted to raiding the wrong house in 2017

-

Swearing in the UK: a colourful history

Swearing in the UK: a colourful historyIn The Spotlight Thanet council's bad language ban is the latest chapter in a saga of obscenity

-

Should there be a legal obligation to act as a good Samaritan?

Should there be a legal obligation to act as a good Samaritan?Talking Point The moral and political maze of helping strangers in need

-

Why is Alabama pausing its executions?

Why is Alabama pausing its executions?Speed Read Many states are struggling to carry out the death penalty

-

Alex Jones ordered to pay nearly half a billion in Sandy Hook damages

Alex Jones ordered to pay nearly half a billion in Sandy Hook damagesSpeed Read

-

Suspect arrested for 2017 murders of Delphi, Indiana teenagers

Suspect arrested for 2017 murders of Delphi, Indiana teenagersSpeed Read

-

Jan. 6 rioter who dragged D.C. officer Michael Fanone into hostile crowd sentenced to 7.5 years in prison

Jan. 6 rioter who dragged D.C. officer Michael Fanone into hostile crowd sentenced to 7.5 years in prisonSpeed Read