Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance review

Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition features lives affected by the Atlantic slave trade

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In recent years, we have begun to appreciate the extent to which Britain's wealth as a mercantile power was "predicated on the centuries-old rapacious plunder of millions of African people", said Colin Grant in The Guardian. Indeed, "charged traces" of slavery can be found throughout the land: "in fine art and botanical gardens, and in stately homes and museums".

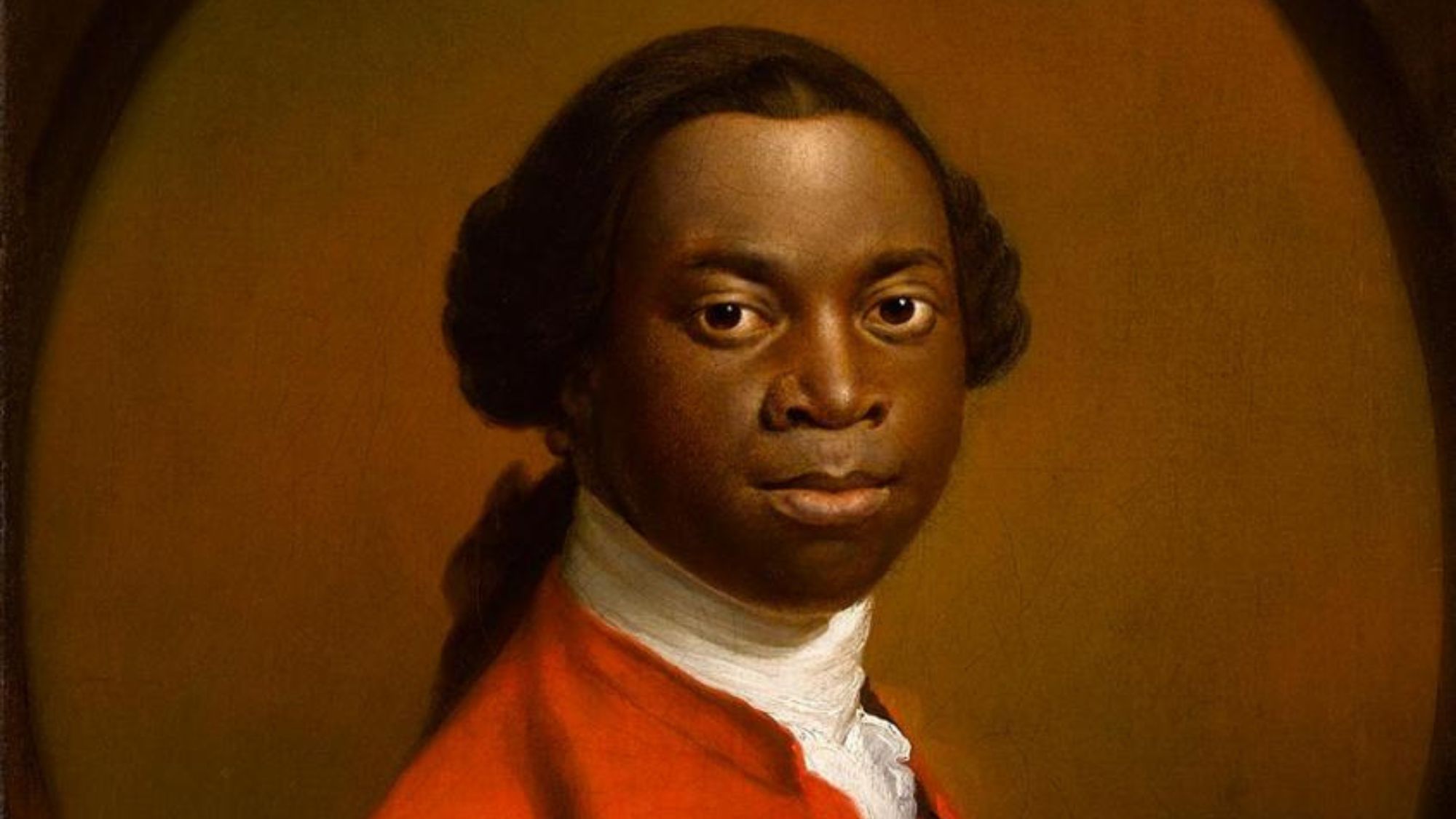

One such is Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum, founded in 1816 by Richard Fitzwilliam, whose fortune derived in part from the Atlantic slave trade. The museum's new exhibition is a "bold" attempt to tackle this legacy head-on, gathering together 120 objects with connections to slavery, from collections in Cambridge and beyond, including paintings, sculptures and artefacts. Highlights include "Portrait of an African Man" (c.1525-1530) by Jan Mostaert, thought to be the earliest portrait of a black person in European art, and an "elegant" English 18th century portrait of an unknown man. It's an "innovative" exhibition that explores how "racial enslavement became normalised" in northern Europe. Frans Post's bucolic "A Sugar Mill" (1650), for instance, renders a Dutch slave plantation "idyllic" and "harmonious".

Around 12 million Africans were enslaved by the Atlantic trade, said Tomiwa Owolade in The Times. The exhibition features many fascinating "portals" to the "largely obscure" lives of those affected. You can see the gold weights once used by the Akan people of west Africa to measure their currency; and wooden sculptures illustrating the "customs and cultures" of Caribbean communities. More "striking" still are paintings of various Dutch masters collected by the family of the Fitzwilliam's founders, notably Dirk Valkenburg's "vivid, textured" depiction of enslaved men, women and children at a "ritual slave party" in 18th century Suriname. Unfortunately, however, the show frequently undermines its successes with a "jarring didacticism" over issues of race and empire. As a result, it often feels more like a lecture, and less like an art exhibition.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The show is "impeccably researched" and "well intentioned", said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. But you frequently wonder what certain exhibits are doing here. The inclusion of a portrait produced by Rembrandt's studio, depicting a man wearing a breastplate, is justified by the fact that the wooden boards on which it was painted "came from a Dutch colony in Brazil". Elsewhere, a pair of "tortoiseshell tongs" used to "pick up lumps of sugar" makes the cut on account of that commodity's "murderous" connotations.

Slavery was of course "abhorrent", and it is "important to acknowledge past wrongs". Yet exhibitions focusing on the slave trade have almost become a "default mode for our museums and galleries". Consequently, this show is rather less daring, and rather less interesting, than it wants to be.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (01223-332900; fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk). Until 7 January 2024

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Josh D’Amaro: the theme park guru taking over Disney

Josh D’Amaro: the theme park guru taking over DisneyIn the Spotlight D’Amaro has worked for the Mouse House for 27 years

-

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentary

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentaryTalking Point The film has played to largely empty cinemas, but it does have one fan

-

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’The Week Recommends Richard Linklater’s homage to the French New Wave

-

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel Universe

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel UniverseThe Week Recommends A Marvel series that hasn’t much to do with superheroes

-

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcom

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcomThe Week Recommends ‘Refreshingly informal’ film based on the life of British comedian John Bishop