Why Biden's Medicare drug price breakthrough is a 'BFD'

Everything you need to know about the biggest changes to U.S. health policy since the Affordable Care Act

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"President Biden is on the verge of his own crowning health-care achievement to call, in his words, a BFD," Rachel Cohrs writes at Stat News, nodding to Biden's sotto voce assessment to then-President Barack Obama that passing the Affordable Care Act was a "big f---ing deal."

As soon as the House passes the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Biden signs it, Democrats will have set in motion the most significant changes to U.S. health policy since Obama's ACA BFD in 2010, with a specific goal of lowering drug costs for Medicares's 64 million beneficiaries. Here's how the IRA aims to bring down health care costs for seniors:

What's in the IRA's Medicare changes?

The legislation will cap out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 a year for enrollees in Medicare's Part D drug program, penalize drugmakers who raise Medicare drug prices higher than the inflation rate, scrap a 5 percent coinsurance requirement for Part D catastrophic coverage, cap the growth of premiums at 6 percent, and ensure that seniors pay nothing for vaccines, some of which — like the shingles vaccine — are quite expensive.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But the biggest change, Cohrs writes, is that after two decades of thwarted promises, "Democrats are finally on track to break the firewall between the pharmaceutical industry and the Medicare program." The Medicare Part D drug benefit, enacted in 2003 during the George W. Bush administration, prohibited the federal government from negotiating for lower drug prices, and Democrats have been pushing to change that ever since.

"For too long, Medicare has been forced to contend with Big Pharma with one hand tied behind its back — that ends when this bill is signed into law," said Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the measure's chief architect.

What about people not on Medicare?

Democrats wrote the legislation with the goal of reducing prescription drug costs for Americans covered by private insurance, not just seniors on Medicare, but because they passed the IRA through the Senate using the filibuster-proof budget reconciliation process, the bill had to adhere to specific criteria. Senate Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough, the arbiter of reconciliation rules, allowed the excessive price hike penalty and a $35 cap on insulin costs for Medicare recipients but threw out those provisions for Americans covered by private insurance.

Democrats and seven Republicans tried to cap monthly insulin costs at $35 for all Americans anyway, but 43 Senate Republicans filibustered that attempt. Yet aside from possibly insulin, drug costs are generally a much bigger deal for seniors than younger Americans.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

According to a 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, 89 percent of U.S. adults 65 and older are taking prescription drugs versus three-quarters of people 50 to 64 and half of those 30 to 49; 54 percent of seniors reported taking four or more drugs. The survey also found that 21 percent of older Americans reported skipping their medications over the past year because of the cost.

Do the changes kick in right away?

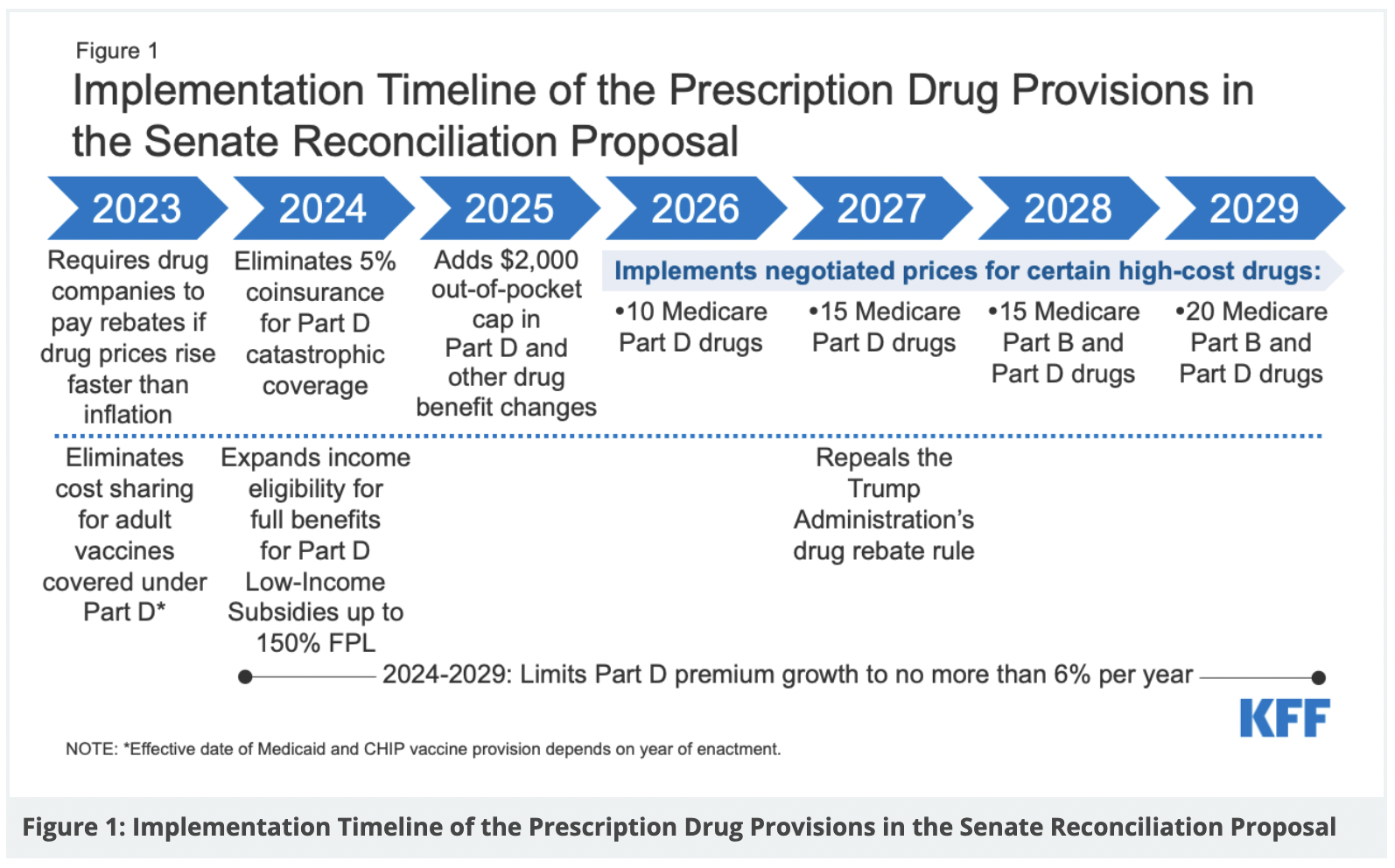

Not most of them. The mandatory rebates for higher-than-inflation drug price hikes start in October, and the elimination of cost-sharing for vaccines takes effect in 2023. The end of catastrophic coverage coinsurance, expanded eligibility for Part D subsidies, and limits on premiums growth begin in 2024, and the $2,000 out-of-pocket drug cap goes into force in 2025. Medicare must negotiate the price of 10 certain high-cost drugs in 2026, a number that will rise to 15 drugs in 2027 and 20 by 2029.

KFF charted out the timeline in a slideshow it put together to summarize the legislation's prescription drug provisions.

Why can Medicare only negotiate the costs of 10 drugs?

"Implementing Medicare's new negotiating power will be a contentious experiment," and nobody is sure how this new power will affect "the complex dynamic of investors' decisions, pharmaceutical companies' calculations, and the outlook for generic drugs," writes Stat's Cohrs. But the fact that Medicare will even be able to conduct this experiment "is a stunning defeat" and "a stinging rebuke to a pharmaceutical industry that is accustomed to winning in Washington."

"This is like lifting a curse," Wyden told The New York Times. "Big Pharma has been protecting the ban on negotiation like it was the Holy Grail."

"Drugmakers launched a seven-figure ad buy, deployed executives to Capitol Hill, and funneled campaign contributions to pharma-friendly senators, but ultimately Democrats have held their caucus together," Cohrs reports. "While drugmakers' influence watered down the proposal, even the goodwill they earned after developing highly effective vaccines to treat COVID-19 wasn't enough to stop it."

Medicare and the Health and Human Services secretary now have a few years to pick the first 10 drugs — which have to have been on the market for at least nine years and have no generic version for competition — and the well-oiled drug lobby still has plenty of opportunities to shape the bill's implementation and drug selection.

What do drugmakers say?

"Today's vote may feel like a political win for Democrats, but it's really a tragic loss for patients," said Steve Ubl, chief executive of the main drugmaker lobbyist group, PhRMA.

"Republicans, and the pharmaceutical industry, insist that the measure will stifle innovation and reverse progress on therapies and treatments, including those for cancer care," but the bill's proponents argue that "new treatments are meaningless if patients can't afford them," the Times reports. "The promise of Medicare, enacted in 1965, has always been that it would take care of older Americans."

The drugmakers do have a "plausible concern" about reduced profits leading to less research and development on future drugs, "but most experts believe that the pharmaceutical industry will remain plenty profitable after the changes," David Leonhardt writes at the Times. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office "estimates that the law will reduce the number of new drugs introduced over the next 30 years by about 1 percent," or 15 drugs.

"It doesn't seem that big a deal," KFF's Juliette Cubanski told Leonhardt.

What do Americans say?

"In the years since Medicare Part D was introduced, polling has consistently found that a vast majority of Americans from both parties want the federal government to be allowed to negotiate drug prices," the Times reports. Former President Donald Trump "embraced the idea, though only during his campaign."

A KFF survey from October 2021 found that only 6 percent of respondents agreed that "drug companies need to charge high prices in order to fund the innovative research necessary for developing new drugs," while 93 percent said "even if U.S. prices were lower, drug companies would still make enough money to invest in the research needed to develop new drugs." That latter view, KFF said, was "consistent across partisanship and age groups."

The survey, which interviewed 1,146 U.S. adults and has a margin of sampling error of ± 4 percentage points, also found overwhelming support for having the federal government negotiate drug prices. Eighty-three percent of adults "strongly" or "somewhat" favored allowing the government to negotiate prices with drug companies, including 84 percent of adults 65 and older. An equal 83 percent agreed that the cost of prescription drugs is "unreasonable."

But just because these changes are broadly popular doesn't mean they will be political winners for Democrats, given the time lag in implementation, lack of awareness that the government is behind the reduced costs, and the fact that a lot of the changes will be invisible to consumers, KFF's Cubanski tells the Times. "These are meaningful changes," she said, "but most people may not necessarily notice that things are changing for the better."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.