Legally rigging elections?

State legislatures are using computer-aided gerrymanders to ensure that the dominant party stays in power.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

State legislatures are using computer-aided gerrymanders to ensure that the dominant party stays in power. How does gerrymandering work? Here's everything you need to know:

How does gerrymandering work?

Under the Constitution, state legislatures redraw congressional districts every 10 years to account for census-documented population changes. To ensure equal representation, these districts must be roughly even in population. But since the early 19th century, legislatures have often engaged in creative boundary drawing to guarantee that most congressional seats will go to the party in control of the legislature. As a simple example, the party in power can take a district in which the opposition draws 50 percent of the vote and divide it in two, ensuring the minority party will lose both districts. Gerrymandering— named after 19th-century Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry—has become far more sophisticated and aggressive in recent years, as consultants armed with algorithms and voter databases have unleashed a frenzy of partisan mapmaking. In 2012, Democratic candidates for the House received 1.4 million more votes than Republicans, but the GOP came away with a 17-seat advantage. For the 2022 midterms, only 18 states have finalized their maps thus far, but redrawn districts now virtually guarantee that Republicans will flip at least five seats.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What states do this?

It's common practice in the 39 states where state legislatures— as opposed to nonpartisan commissions or other bodies— oversee redistricting. The states in which Democrats control the legislatures aggressively gerrymander; Illinois and Maryland contain some of the most heavily gerrymandered and misshapen congressional districts in the country. But this year, Republicans firmly control 20 state legislatures, including four of the six states that are gaining congressional seats: Texas, North Carolina, Montana, and Florida. Racial and ethnic minorities, who tend to favor Democrats, contributed much of that population growth in these states, but Republican gerrymandering will water down their power. Texas owes 95 percent of its 2010–2020 growth to nonwhite and Hispanic groups; only about 40 percent of the state population now is non-Hispanic white. Yet Republicans' 2022 map added one majority-white district to the 22 that currently exist while eliminating one of its eight majority-Hispanic districts and its only majority-Black district. Despite Texas' fast-growing nonwhite population, FiveThirtyEight rates 24 out of the state's 38 congressional districts as likely Republican strongholds.

Is that legal?

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 bans gerrymandering designed to hurt racial and ethnic groups, but it does not prohibit gerrymanders for partisan reasons. In 2017, the Supreme Court struck down GOP-controlled North Carolina's initial 2011 map, which heavily favored Republicans, based on strong evidence the legislature intended to minimize the influence of Black voters. Republicans responded by drawing an even more politically skewed map, which led to another lawsuit. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court's conservative majority ruled in 2019 that regulating partisan gerrymandering was "beyond the reach of the federal courts." The ruling enables lawmakers to insist that gerrymandered maps that dilute the power of minorities do so as an unintentional byproduct of drawing lines for partisan advantage.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What's happening this year?

A massive amount of extreme gerrymandering. The approved 2022 map for North Carolina, a swing state that went for Trump by less than two percentage points, would give Republicans 10 of 14 seats. One of the two Democratic-leaning seats that was eliminated has been represented since 2004 by G.K. Butterfield, an African-American congressman. Voting-rights advocates have filed three lawsuits arguing that the map is so severely gerrymandered that it violates the principle of one person, one vote. In Wisconsin, another narrowly divided swing state, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers last month vetoed a proposed map that gave the GOP six out of eight House seats. The job of redistricting now falls to Wisconsin's Supreme Court, where conservative justices hold a majority.

Can the system be fixed?

Yes, in theory, but numerous attempts at reform have failed. In 2018, 75 percent of voters in Ohio supported amendments to the state constitution that require the legislature to get some bipartisan support for its redistricting map. Republicans commandeered the process anyway, leaving Democrats with just two seats out of 15. Reformers often call for putting redistricting in the hands of an independent or bipartisan commission; 13 states currently do this. But sometimes, the results are no less skewed: The latest proposed map in California, which draws its maps via independent commission, gives Democrats 75 percent of the congressional seats despite their having just 59 percent of statewide votes. In the Democrats' proposed Freedom to Vote Act, partisan gerrymandering would be banned nationwide. But that bill has been stymied by a likely Republican filibuster in the Senate. Without support from the Republican and Democratic incumbents who benefit from gerrymandering, efforts to ban it will probably go nowhere. "In this crazy system," said New York Public Interest Research Group executive director Blair Horner, "partisan consideration often rules."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale

-

Why the Bangladesh election is one to watch

Why the Bangladesh election is one to watchThe Explainer Opposition party has claimed the void left by Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League but Islamist party could yet have a say

-

The world’s most romantic hotels

The world’s most romantic hotelsThe Week Recommends Treetop hideaways, secluded villas and a woodland cabin – perfect settings for Valentine’s Day

-

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election win

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election winSpeed Read President Donald Trump congratulated the conservative prime minister

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Dutch center-left rises in election as far-right falls

Dutch center-left rises in election as far-right fallsSpeed Read The country’s other parties have ruled against forming a coalition

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

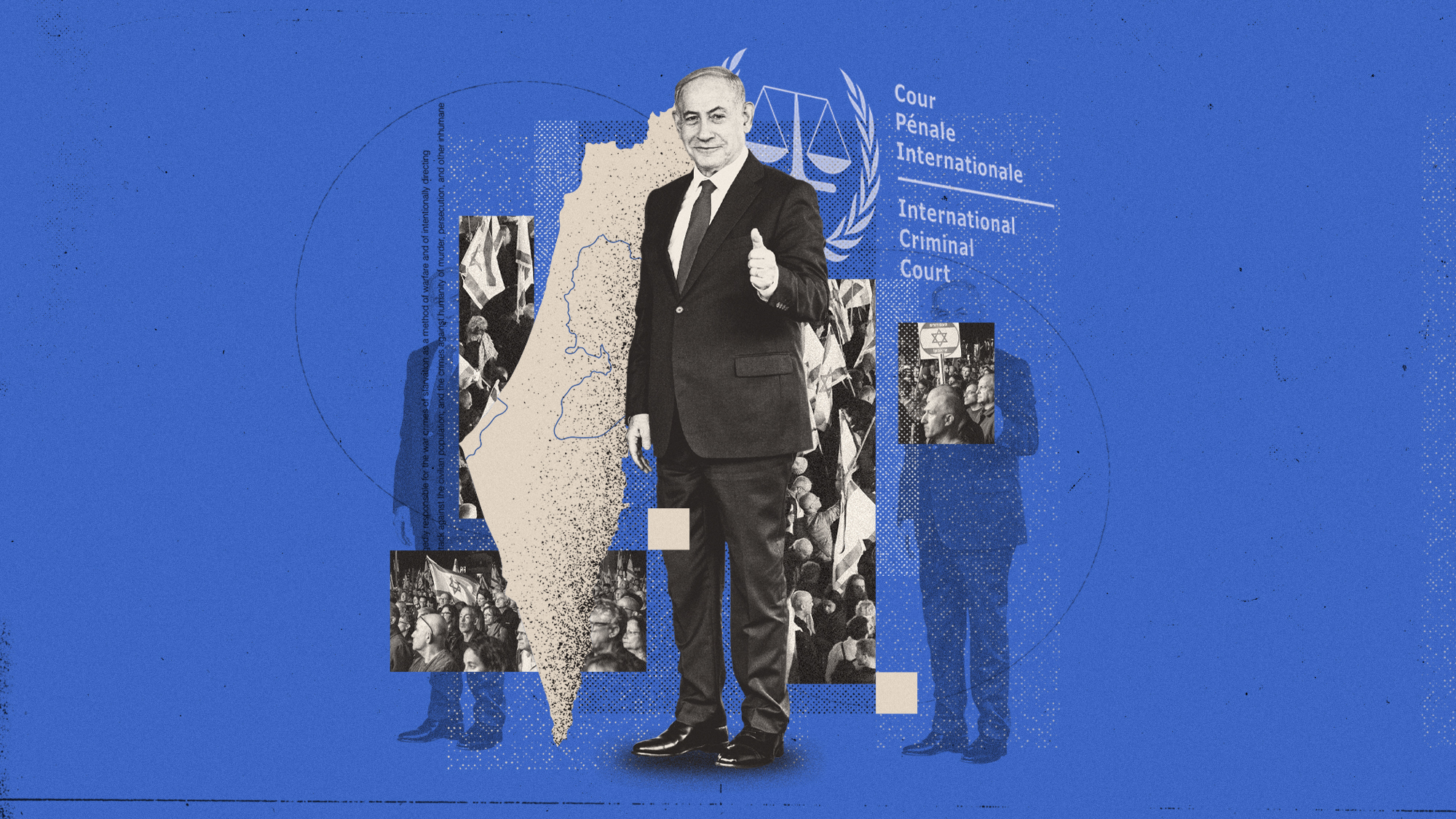

Has the Gaza deal saved Netanyahu?

Has the Gaza deal saved Netanyahu?Today's Big Question With elections looming, Israel’s longest serving PM will ‘try to carry out political alchemy, converting the deal into political gold’