Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate change

Tackling the second most significant contributor to global warming could have an immediate impact

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

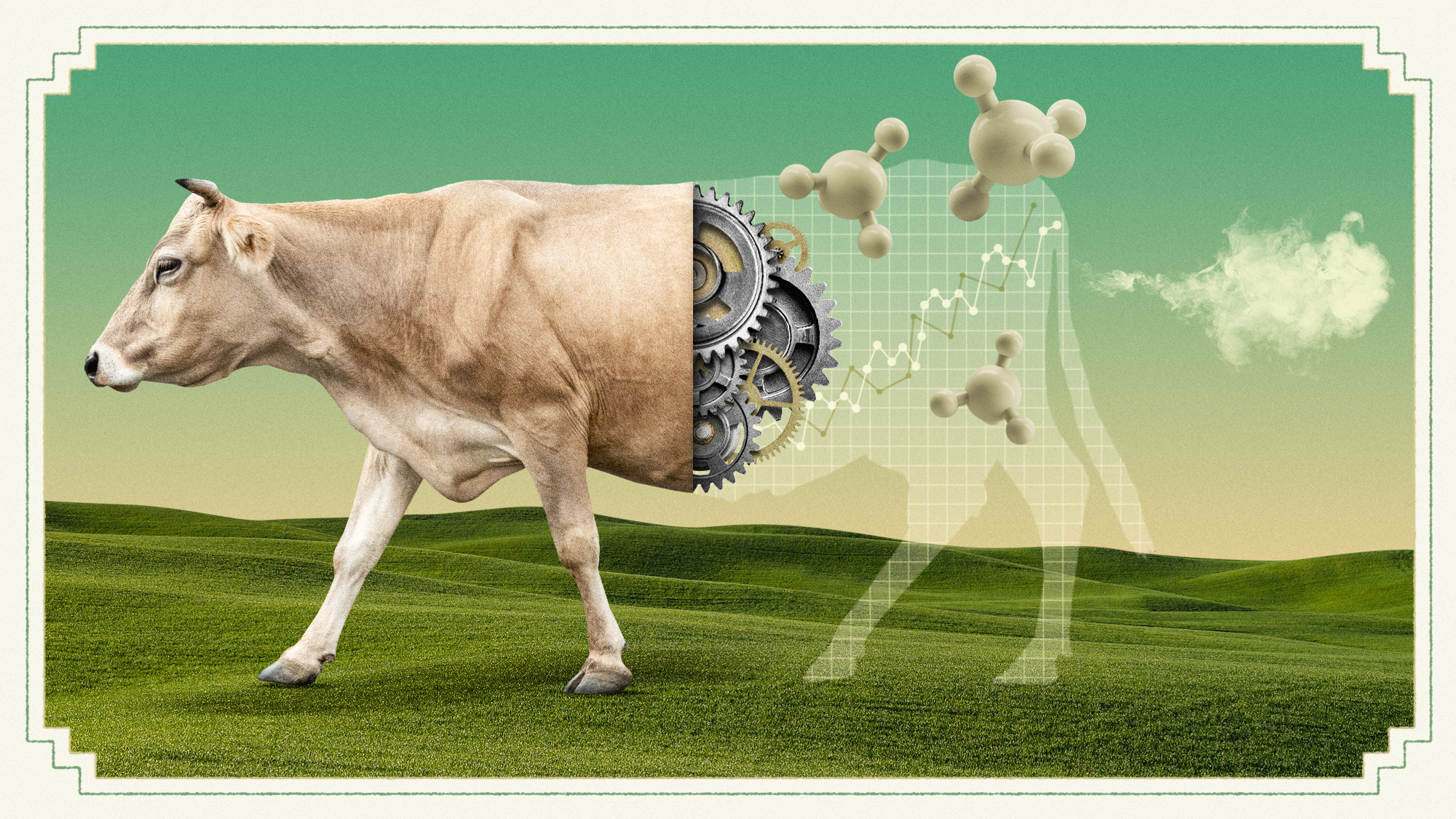

Marks and Spencer is to invest £1 million on a diet plan for dairy cows in the latest bid by big business to curb methane emissions.

The retailer is aiming to "slash" up to 11,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually by making the burps and farts of its 40 herds of pasture-grazed milk cows "more eco-friendly", said the Daily Mail. M&S claims that switching them to a diet derived from mineral salts and a by-product of fermented corn will reduce methane production during digestion, cutting the carbon footprint of the cows' milk by 8.4%.

How much damage does methane cause?

Aside from carbon dioxide, methane is the "most significant" contributor to climate change, said New Scientist. Methane occurs naturally but is also caused by humans, most commonly during fossil fuel production, "due to leaks from wells, coal mines, pipelines and ships".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Landfills are also a significant contributor, because of methane released by decomposing food waste, but the second biggest emitter is through the burping and defecation of livestock. With "around 1.5 billion cows on the planet being raised as livestock", said Vox, the production of meat and dairy is a "climate problem we've struggled to solve".

Methane is responsible for "about a quarter of overall warming", said New Scientist. Although it does not stay in the atmosphere for anywhere near as long as carbon dioxide, methane is "around 30 times more potent than CO2" – and there has been a "steady rise" in methane emissions for almost two decades. The long-lasting effects of CO2 will "increasingly dominate over time", but tackling non-CO2 gases such as methane will bring a "significant near-term effect".

How is it being combatted?

Given that methane only lasts in the atmosphere for around 12 years, many see it "as low-hanging fruit for climate solutions", said The Associated Press (AP). At the UN's Cop26 climate summit, in 2021, a "global methane pledge" was launched to combat rising emissions. Yet while 155 countries have signed up, the pledge does not include an agriculture target and little improvement has been made.

At last year's Cop28, further plans were announced to try to reduce methane emissions by 30% before 2030, with more than $1 billion in extra funding and reduction commitments by leading methane producers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But some countries, notably India, have yet to commit to any such pledges. India is the "world's largest milk producer", said AP, and is home to around 303 million bovine cattle that are responsible for around 48% of all of the country's methane emissions.

There are some promising practices that could help stem the flow of agricultural methane, including "new breeding and feeding techniques", said the BBC. But it is human diets, and the consumption of meat and dairy, that are the "ultimate blind spot holding up methane reduction".

What next?

An independent monitoring business is using satellites to determine the amount of methane in the Earth's atmosphere and where the biggest emissions are coming from, with a primary focus on leaks from oil and gas fields.

The data collected is being fed back to "scientists, policymakers, industry and the public", said Gina McCarthy in The Guardian, and demonstrates how "collective efforts" could help "avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis". What has become clear is that cutting methane levels "is the most efficient way to slow global warming in our lifetimes", and that "we have the chance – and the obligation – to do so".

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question Trial will determine if Meta, YouTube designed addictive products

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air