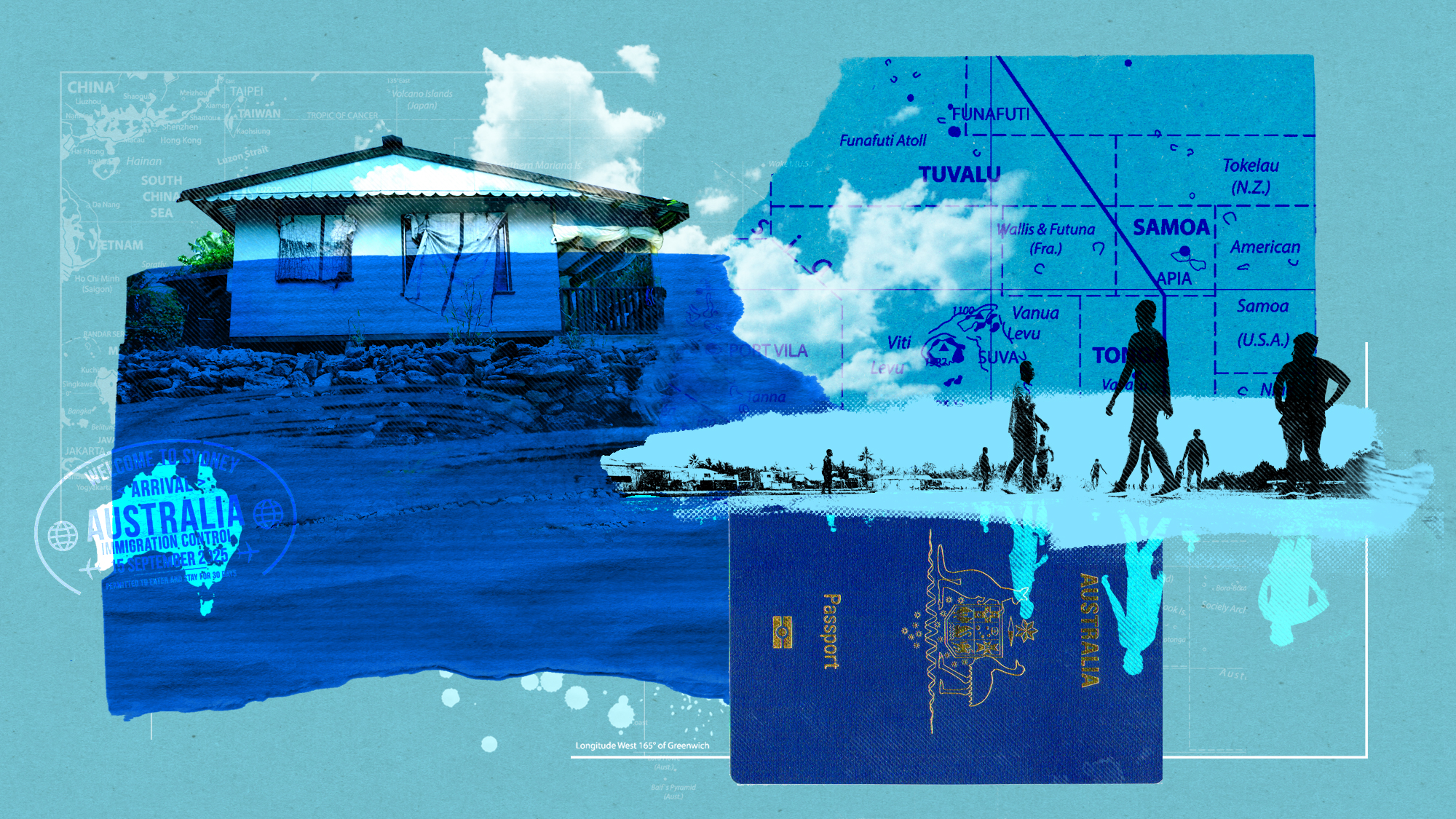

Tuvalu is being lost to climate change. Other countries will likely follow.

Sea level rise is putting islands underwater

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The island nation of Tuvalu is becoming the first country to be completely lost due to rising sea levels. However, the country is possibly only the first of many without actions taken to mitigate climate change.

Country casualty

Tuvalu, located in Oceania, is expected to be completely underwater by 2050. The island nation with a population of just 11,000 is setting a precedent to become the first country to have to permanently evacuate. To do this, Australia and Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union Treaty, which is an "agreement that provides for a migration scheme that will allow 280 Tuvaluans per year to settle in Australia as permanent residents," said Wired. This is the first climate visa of its kind. "We received extremely high levels of interest in the ballot with 8,750 registrations, which includes family members of primary registrants," the Australian High Commission in Tuvalu said in a statement. The visa operates through a ballot system and "will grant beneficiaries the same health, education, housing and employment rights enjoyed by Australian citizens," said Wired. Tuvaluans will also be able to return to their home country if conditions allow.

However, Tuvalu is perhaps just the first of many countries or regions that will have to evacuate because of climate change. "From historic droughts to catastrophic floods, these extreme variations disrupt lives, economies and entire ecosystems," said Albert van Dijk, a professor at Australian National University, to Wired. Unfortunately, "Tuvalu is the canary in the coal mine, and that coal mine is rapidly filling with water," said Vice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

More disappearing ahead

While not on the scale of an entire country, there have been other times when almost full populations made moves to evacuate where they lived. In 2024, approximately 1,200 members of the Indigenous Guna community relocated from the island of Gardi Sugdub off the coast of Panama to the mainland. This was also due to rising sea levels slowly sinking the island. This was "one of the first planned migrations in Latin America due to climate change," said AFP. In a similar vein, nearly 300 people moved from Newtok, Alaska, because the village was perched on permafrost, which began to thaw dangerously and erode the banks. More countries are likely to become less habitable in the future. By 2070, over "3 billion people could find themselves living outside of humanity's 'climate niche,'" said the San Francisco Chronicle. Island nations are especially at risk.

The Maldives are an archipelago comprising almost 1,200 islands, most of which are under four feet above sea level, making them especially vulnerable to changes in ocean levels. "Even a minimal rise in water levels can lead to major changes, such as coastal erosion, salinization of drinking water sources and more frequent flooding," said Wodne Sprawy, a Polish publication. As preparation, the Maldives government has "explored plans to purchase land on higher ground in other countries," said NASA. Almost every other island nation faces similar risks, including Kiribati, the Solomon Islands, Fiji and Vanuatu.

The U.S. is also not free from the threat of relocation. Several coastal states, such as Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Alabama and Mississippi, are at risk of losing their coastlines. New York City, Chicago and several cities in California are also sinking, which could in time require evacuation. In addition, the Gulf of Mexico is rising three times faster than the global average, according to a study published in the journal Nature. Without measures to combat climate change, mass migration may be the only way to survive.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away