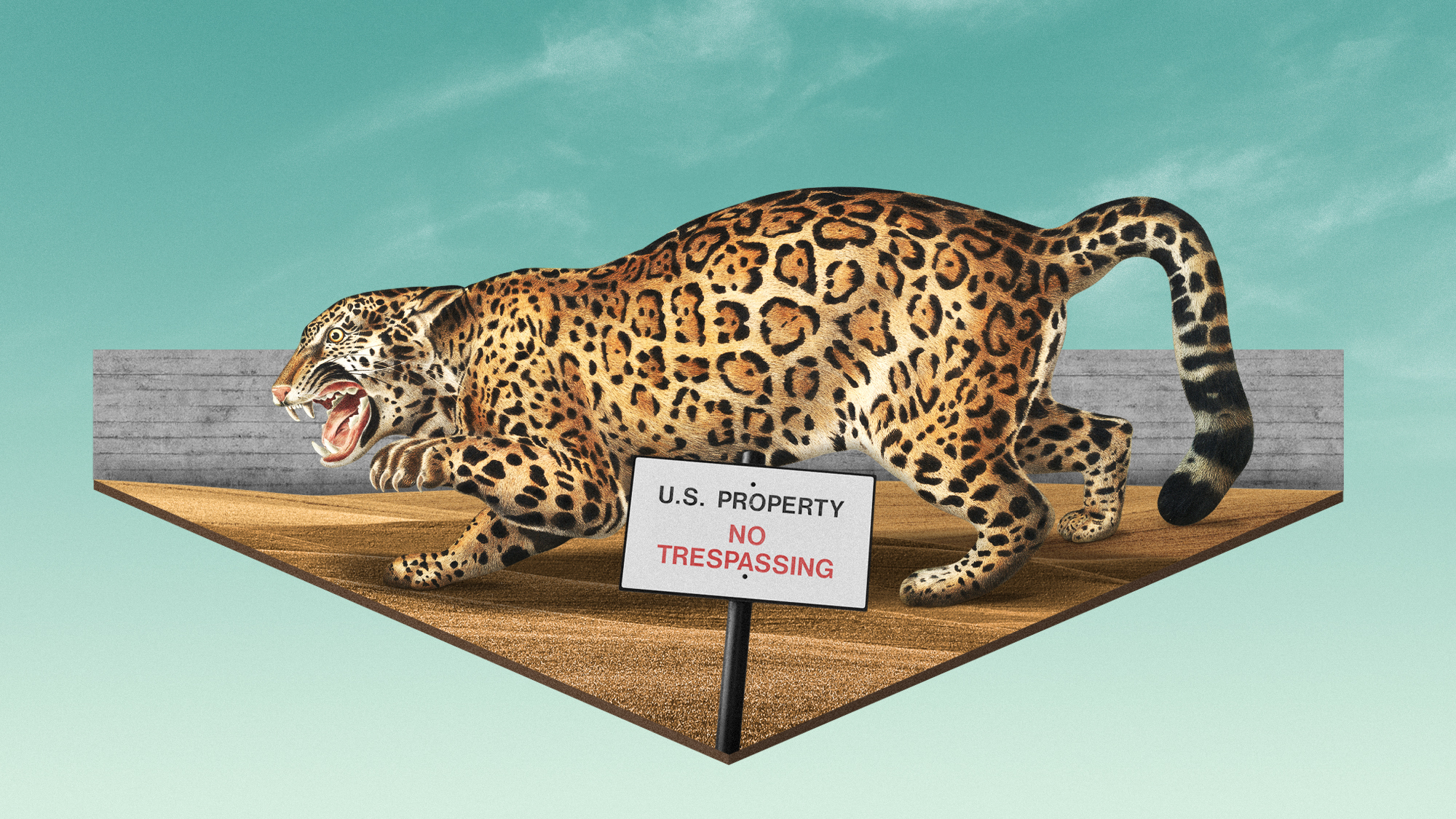

The revived plan for Trump's border wall could cause problems for wildlife

The proposed section of wall would be in a remote stretch of Arizona

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With President Donald Trump introducing a resurrected plan for his U.S.-Mexico border wall almost immediately after retaking office, some have expressed concern that it could affect more than the people in the region. A new report has claimed that Trump's plan for a 25-mile stretch of wall in Arizona could have devastating impacts on the area's wildlife, much of which is already endangered or threatened.

How could the border's wildlife be affected?

The wildlife in question lives in Arizona's San Rafael Valley, a mountainous region along the southern border. The valley is "one of the last vital pathways for wildlife movement," and "jaguars, ocelots, black bears, pronghorn and many other species rely on this corridor to move freely between the U.S. and Mexico," according to a report from the Center for Biological Diversity.

At least 17 endangered or threatened species have been photographed in the valley, which is also home to the "highest number of modern jaguar detections anywhere in the U.S.," said the Center for Biological Diversity. The valley currently has only low wire fencing that allows animals to pass through. Building a wall in this area "would block species movement, destroy protected habitats, and inflict irreversible damage on critical ecological linkages." The wall would also likely include high-intensity artificial lighting similar to sports stadiums. This could "degrade the valley's natural light-dark cycle, which governs critical behavioral and physiological processes in wildlife."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A border wall "modifies the whole ecosystem around that community," Dr. Ganesh Marín, a biologist who studies wildlife movement with Conservation Science Partners, said to The New York Times. Beyond restricting movement, a border wall "could also cause smaller prey animals to avoid the area," resulting in "cascading negative effects."

What is being done?

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol is soliciting bids for the wall's construction, with the Department of Homeland Security's press release notably not mentioning plans for the area's wildlife. There have been some efforts by outside groups to try to halt the administration's plans.

The Center for Biological Diversity is "suing to stop further construction of the border wall in Arizona," saying the construction is "unconstitutional by pushing aside 30 laws passed by Congress," said KOLD-TV Tucson. The lawsuit "challenges the federal government's unconstitutional power grab," Russ McSpadden, the center's Southwest conservation advocate, told KOLD. If the wall is completed, it "will destroy the border's last remaining significant wildlife corridor," the center said in its initial court filing.

Other activists are "girding for a new battle" but fear that "border builders may conquer the remote zones that eluded them the first time — the very zones most conducive to movement" of wildlife, said the Arizona Republic. Many also question what the wall will accomplish, given that "most migrants and drugs come through or near populated border checkpoints." The Trump administration has also "slowed the flow of migrants across the Southwestern border" without the wall in place.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These activists maintain that the wall would be "easily breached and gives merely a false sense of security" while greatly hindering wildlife, said the Arizona Republic. It's the "border agents and their superior technology — and not the wall — that stop unauthorized crossings."

"It's a physical barrier" that would harm the wildlife but not stop immigration, Valerie Gordon, an American conservationist in the region, said to the Arizona Republic. "It's an emotional barrier. It's a pointless barrier."

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

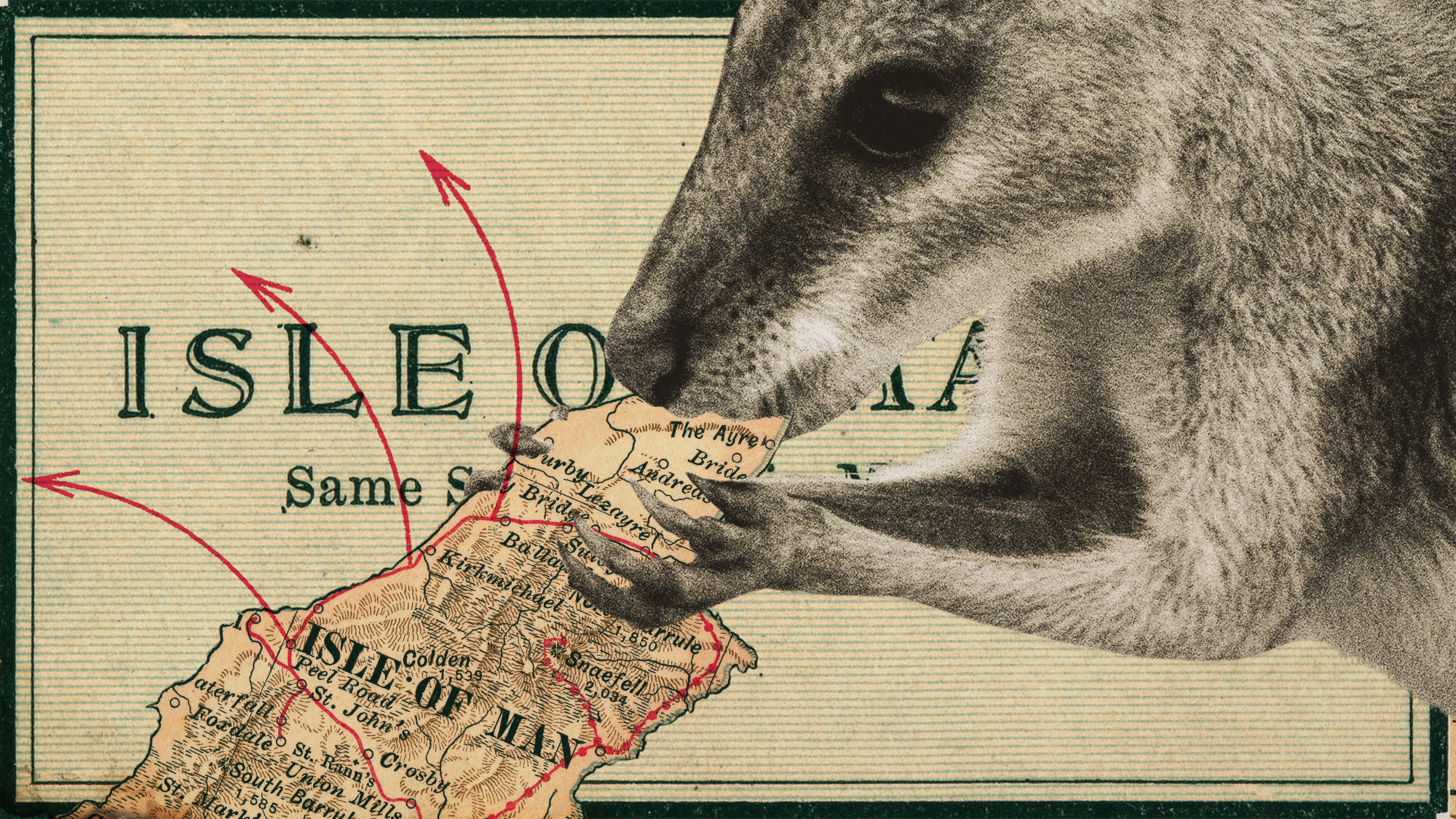

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’Under the Radar The Australian marsupial has ‘colonised’ the Isle of Man and is now making regular appearances on the UK mainland

-

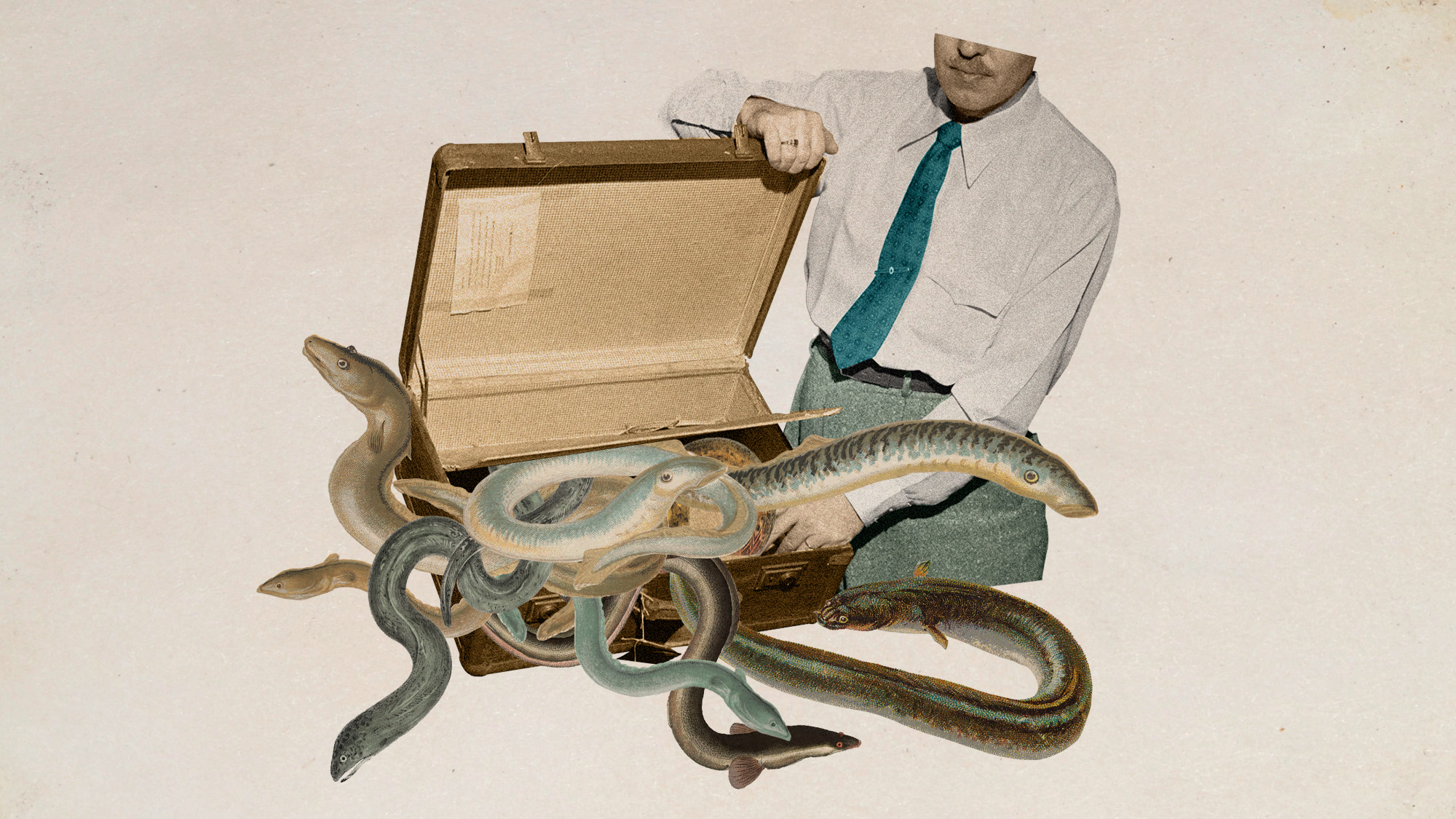

Eel-egal trade: the world’s most lucrative wildlife crime?

Eel-egal trade: the world’s most lucrative wildlife crime?Under the Radar Trafficking of juvenile ‘glass’ eels from Europe to Asia generates up to €3bn a year but the species is on the brink of extinction

-

How climate change poses a national security threat

How climate change poses a national security threatThe explainer A global problem causing more global problems