How Is Trump's wall working?

Nearly a decade after promising to 'build the wall' between the US and Mexico, Donald Trump has returned to the White House on an anti-immigration platform, vowing to drastically stem southern border crossings

Rafi Schwartz, The Week US

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Aside from his longstanding campaign pledge to "Make America Great Again," there is arguably no more memorable sound bite from President Donald Trump's first term in office than his promise to "build a great, great wall on our southern border" — a project for which, he insisted, Mexico would pay. "The Wall" quickly became a regular fixture at his political rallies, and a shorthand shibboleth to express support for Trump's broader anti-immigration policies.

Throughout his first administration, Trump would regularly brag about the progress of his proposed border wall, even as actual construction remained mired in lawsuits, red tape and political reality. As he returns to the White House for a second term, Trump has continued his previous efforts to curtail immigration into this country along the southern border — albeit with an emphasis on military intervention and deportation rather than construction. Still, as Trump's self-proclaimed "golden age" gets underway, it's worth exploring just how effective his one-time signature project has been.

How much wall did Trump build?

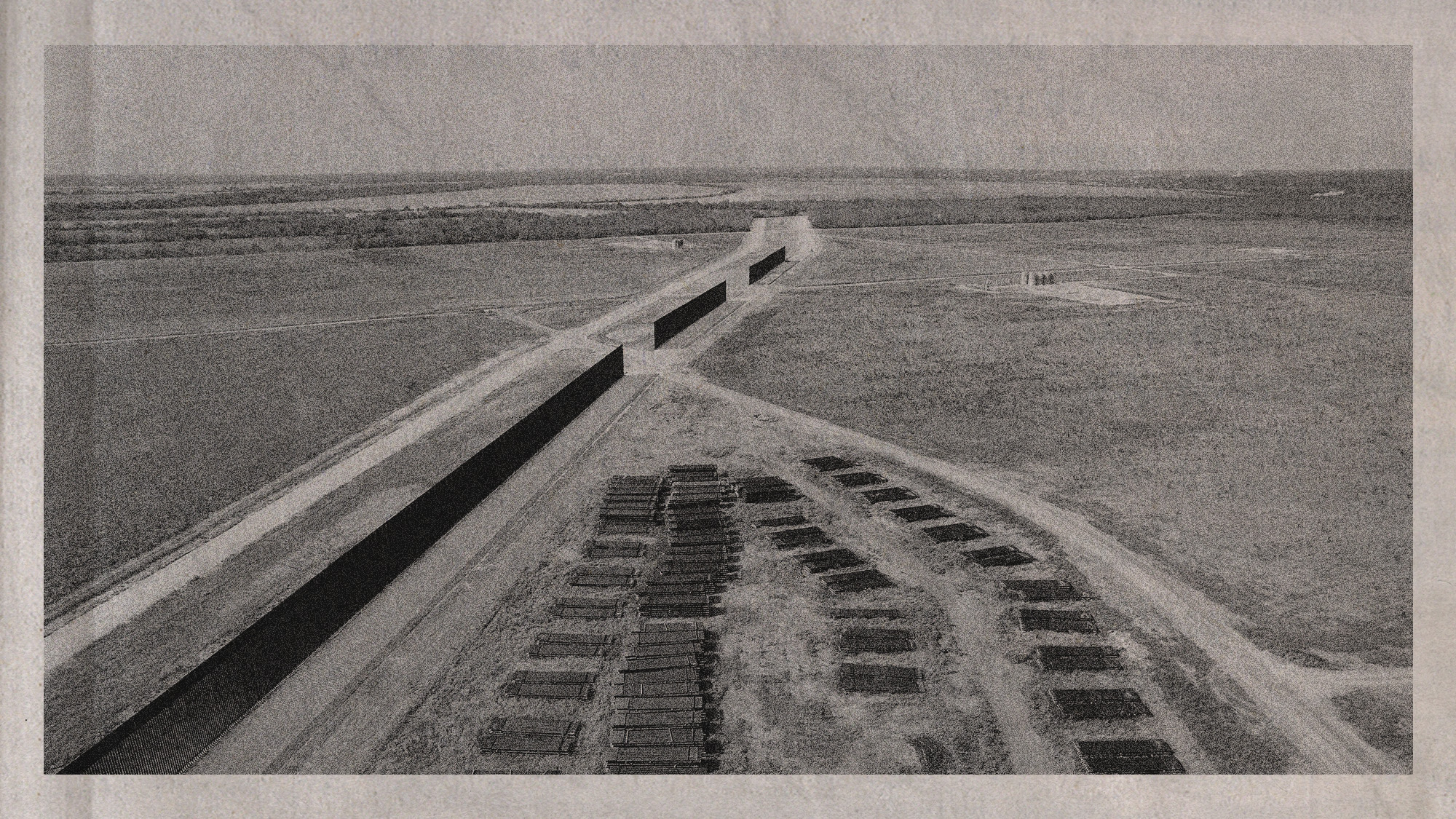

At a May 2023 CNN town hall, former President Donald Trump claimed that his administration finished building a wall along the 1,954-mile border separating the U.S. and Mexico. But according to a Customs and Border Protection report written two days after Trump left office in 2021, about 458 miles of the wall were completed under his administration, with another 280 miles identified for construction but never finished. Of those 458 miles, just 52 covered sections of the border that hadn't previously had a barrier. The other 406 replaced shorter barriers that already existed with a fence made of reinforced hollow steel bollards ranging from 18 to 33 feet high. In some sections, lights, cameras and sensors accompanied the new barriers; in others, a secondary fence was built to reinforce an existing one. The project cost an estimated $15 billion, with the money coming from Department of Defense funds and appropriations from Congress. Combined with fencing that pre-dated Trump's presidency, about 700 miles — mostly along public land in Arizona and New Mexico — now have a barrier. That same month, House Republicans passed an immigration bill calling for resuming construction.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Is the new wall effective?

It does not seem to be deterring migrants from coming to or crossing the border. The number of crossings, as measured by apprehensions at the border, rose steeply during Trump's term, more than doubling from 2018 to 2019. The pandemic initially slowed migration, but by spring 2021, the number of unlawful border crossings and arrests — separate from those legally applying for asylum — had risen above the totals recorded in most months before Trump began building the wall. Border Patrol have maintained, however, that the towering bollards have served a purpose. "There is a psychological reason," said Chief Patrol Agent Patricia McGurk-Daniel. "It's a high fence. You don't want to cross it, but it's also tall enough our agents can see through." Professional smugglers and determined migrants, however, have found myriad ways to get through and over the wall.

How do they do that?

Saws and other inexpensive power tools were used to cut holes in the wall more than 3,200 times between 2019 and 2021, costing the government $2.6 million in repairs. From October 2021 to September 2022, the wall was breached 4,101 times, an average of about 11 breaches per day. Some smugglers have essentially created "doors" in the wall by disguising the holes they created in the bollards with tinted putty that they remove every time they want to help people cross. Smugglers have also dug tunnels or climbed over the barrier on ladders, or crossed at one of the wall's many gaps. Paths, initially built by construction crews to help them reach remote border areas, now guide migrants who make it across. "There are so many access roads that it's possible for someone to walk right up to places where the wall ends and have someone just pick them up," said conservationist Valer Clark to The New York Times during the first year of President Joe Biden's administration.

Is there a human cost?

The wall has made crossing the border more dangerous. Migrants circumventing the wall have drowned swimming across the Rio Grande and collapsed from heat exposure in the desert. Some of those climbing over it with ladders or by hand have fallen as much as 30 feet, suffering severe injuries — some fatal. From 2019 to 2021, the University of California at San Diego Medical Center recorded 375 patients admitted due to falls. In fiscal year 2022, at least 853 migrants died crossing the border, breaking the previous year's record of 546. Border Patrol also recorded about 22,000 rescues of distressed migrants in that time, up 72% from the previous year. In 2021, the United Nations-affiliated International Organization for Migration said the U.S.-Mexico border was "the deadliest land crossing in the world," after 728 of that year's 1,238 migrant deaths en route to America occurred at the border itself.

What changed under Biden?

Despite an 11th hour attempt to finish the wall in the waning days of the first Trump administration, tens of thousands of heavy steel bollards worth $350 million were left unused, rusting in the southwest sun. President Biden, who campaigned on a promise not to build "another foot" of wall, allowed some construction to continue to honor existing contracts and filled some gaps in Arizona, Texas and California. "Some of the construction was going to have to be finished, or else it would create a legal risk," said a former White House senior official to The New Yorker in 2022. At the same time, Republican governors along the border built "new sections of barriers in their states with hundreds of millions of dollars in government and private funding," as the Biden administration's effort to cancel pre-existing wall construction contracts signed under the Trump White House were hampered by federal regulations.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why the talk of building more?

In May 2023, President Biden ended Title 42, the Trump-era immigration policy that allowed authorities to turn back migrants without granting them the right to seek asylum, replacing it with a tougher asylum policy. After an initial spike in the number of migrants encountered by Border Patrol agents in 2023, 2024 saw a 77% decline in encounters thanks to "policy changes on both sides of the border," Pew Research said. Many conservatives, however, remain committed to the wall as a statement about the border, said Andrew Selee of the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute to Politico. "This was always about a larger symbolism about walling off America from outside dangers."

Despite having previously called Trump's wall "un-American," even former Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris seemed resigned to some form of future construction along the border. Her campaign's border security plan called in part for "filling in strategic sections of the wall along the nearly 2,000-mile mile," NBC News said.

The environmental damage

To build his wall, Trump had to bulldoze, dig and tear through land along the border, waiving over 50 environmental laws and regulations. The damage drew strong protests from environmentalists, native tribes and private land owners. Construction damaged streams and led to vegetation removal, creating rapid erosion. Near Arizona's San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, flash floods tore some of the wall's floodgates from their hinges in recent years. Rivers that flow south across the border into Mexico are now contaminated with rust from the wall, killing native fish. In Guadalupe Canyon, in southeastern Arizona, construction crews dynamite-blasted into the mountainside to erect a barrier, altering a critical habitat for endangered cross-border species, including jaguars. "Animals have been migrating through this route for tens of thousands of years," Myles Traphagen, a biologist mapping the impact of the wall, said to The New Yorker. "If we cut off this population, we're essentially altering the evolutionary history of North America."

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

‘The mark’s significance is psychological, if that’

‘The mark’s significance is psychological, if that’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?Today’s Big Question Women lead the resistance to Trump’s deportations