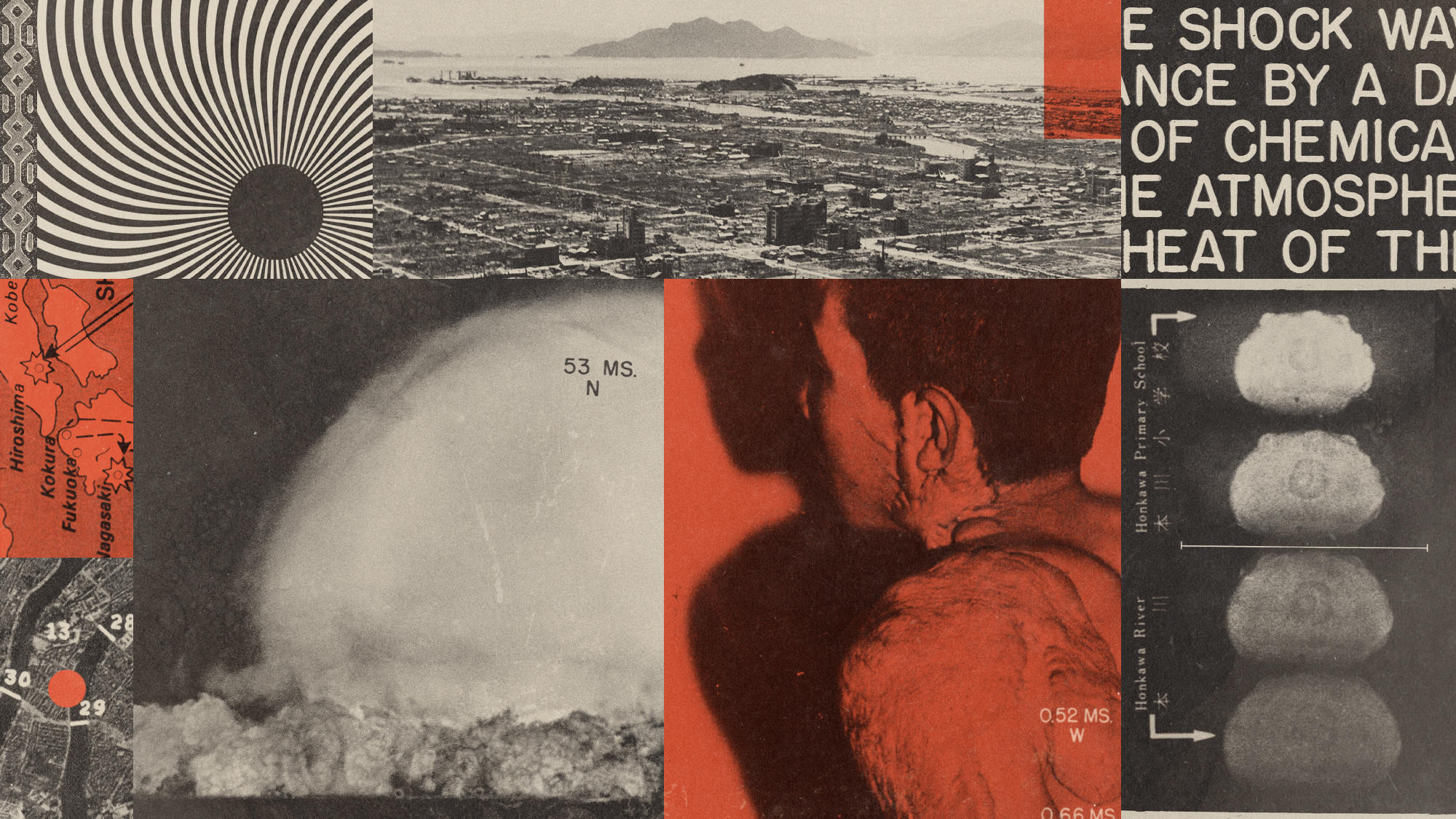

Eighty years after Hiroshima: how close is nuclear conflict?

Eight decades on from the first atomic bomb 'we have blundered into a new age of nuclear perils'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Today marks 80 years since the US dropped the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

More than 140,000 people died – tens of thousands instantaneously – with 70,000 perishing in a second bomb over Nagasaki three days later.

Yet as the world marks the anniversary, it seems that many of today's leaders have failed to learn the lessons of that terrible epoch-defining day.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

The memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seared itself "into the conscience of global leaders and the public", and "cast a long shadow over global efforts to contain nuclear arms", said Stephen Herzog, professor of the practice, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, California, on The Conversation.

From the late 1960s onwards a series of landmark non-proliferation and test-ban treaties sought to limit the number and use of nuclear weapons worldwide.

Eighty years after the first atomic bomb "we have blundered into a new age of nuclear perils", said Jason Farago in The New York Times.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine led then-US President Joe Biden to say that the risk of nuclear "Armageddon" had not been so high since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Earlier this year, the new director of national intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, issued a similar warning that we stand "closer to the brink of nuclear annihilation than ever before".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

China is expanding its own nuclear arsenal, North Korea continues to build its nuclear capabilities, and tensions between nuclear rivals India and Pakistan remain high after a short war earlier this year.

This week, Russia announced it could renew the deployment of short- and intermediate-range nuclear missiles amid mounting tensions with the US. It comes just days after Donald Trump announced he was deploying two US nuclear submarines closer to Russia as a response to what he called "highly provocative" comments by former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev.

The last arms control treaty between the Cold War superpowers – the 2011 New Start treaty which places restrictions on strategic nuclear arms including intercontinental missiles – is set to expire in just six months, and "the very principle of arms control may die with it", said Farago.

"All this with remarkably little outcry." The Federation of American Scientists estimates that there are around 12,000 nuclear warheads remaining on Earth today, "and yet we have let the bomb be absorbed back into Second World War dad history".

What next?

Time was when a US president "treated any declarations about nuclear weapons with utter gravity and sobriety", said Tom Nichols in The Atlantic. Trump's latest outburst on his Truth Social platform signals we have entered a "new era in which the chief executive can use threats regarding the most powerful weapons on Earth to salve his ego and improve his political fortunes".

The same could be said of Vladimir Putin. Since the start of the war in Ukraine the Russian president and his allies have made a series of nuclear threats against Kyiv and its partners.

In response, the US air force is believed to have increased the number of nuclear bombs stationed in Britain, the first time this has happened since the end of the Cold War, Hans Kristensen, nuclear information project director at the Federation of American Scientists, told The Guardian.

It would also indicate that "Nato has changed its policy of not responding with new nuclear weapons to Russia's nuclear threats and behaviour".

The lack of historical perspective, and willingness to learn from history, is a specific problem for a man like Trump who "appears to have no sense of the past or the future", said Nichols. "He lives in the now, and winning the moment is always the most important thing."

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?Talking Point The latest slew of embarrassing emails from Fergie to the notorious sex offender have put her daughters in a deeply uncomfortable position

-

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?Today’s Big Question Since the ceasefire agreement in October, the situation in Gaza is still ‘precarious’, with the path to peace facing ‘many obstacles’

-

Vietnam’s ‘balancing act’ with the US, China and Europe

Vietnam’s ‘balancing act’ with the US, China and EuropeIn the Spotlight Despite decades of ‘steadily improving relations’, Hanoi is still ‘deeply suspicious’ of the US as it tries to ‘diversify’ its options

-

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?Today’s Big Question Analysts say China’s leader is still focused on reunification

-

Trump demands $1B from Harvard, deepening feud

Trump demands $1B from Harvard, deepening feudSpeed Read Trump has continually gone after the university during his second term

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaint

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaintSpeed Read This comes as Trump has pushed Republicans to ‘take over’ voting

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away