Follow the math and free yourself from COVID-19

The vaccines have passed the test. They work. The time to return to normal is now.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you follow the news, and specifically spend a lot of time on Twitter, you'll recognize a pattern in recent debates about the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, someone will declare that it's time to lift all restrictions so life can get back to normal. Then one camp of critics will respond by insisting that there haven't been lockdowns for over 18 months, so COVID is already over for anyone who wants it. Finally, from another direction comes a shriek of outrage: How can you suggest we get back to normal when thousands of people are dying of the virus every single day?

This week it was Yascha Mounk who launched an especially intense iteration of this cycle with a powerful essay at The Atlantic simply titled, "Open everything." Right on cue, both factions of critics descended on him to explain that everything is already open and how dare he advocate leaving the pandemic behind while the Omicron wave is still killing lots of people.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The pattern repeats itself for a reason. Yes, it's time for governments and the private sector to begin lifting remaining restrictions on daily life, as several states acknowledged in the past several days by announcing the end of mask mandates. Such signaling from the top down is important, but it won't bring the pandemic to a close because significant numbers of individuals (especially Democrats) continue to assess risk in a way that leads them to refrain from normal activities, keeping the public life of our country frozen in a state of suspension between lockdown and liberation.

Until those risk assessments change, the pandemic will linger on. But it shouldn't. It's long past time we free ourselves from COVID-19.

But what about that second, recurring objection? The number of daily deaths from the virus appears to be plateauing, but at a very high level of more than 2,000 deaths a day. That's not as high as the peak of the winter wave a year ago, but it's higher than the original surge of deaths during the spring of 2020 and the Delta surge of five months ago. Why should individuals change their thinking about risk and make different choices now than they have over the past two years?

Because readily available vaccines have proven extremely effective at protecting people from the virus. No, they don't protect as well as we once hoped against breakthrough infections or transmissibility, especially when it comes to the highly contagious Omicron variant. Yet they do in most cases protect a vaccinated and boosted individual from getting seriously ill and dying. We can see this from CDC data showing that the incidence of death last October and November from COVID-19 for someone vaxxed and boosted was about 0.1 per 100,000 infections — or about 1 out of a million.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course that figure includes everyone vaxxed and boosted — the young, the very old, those who are otherwise healthy, those with multiple co-morbidities, and so forth. So the chance of dying from a COVID-19 infection will still vary somewhat from that figure for any given person. But still, the number, even treated as a very rough estimate for any specific individual, is strikingly low.

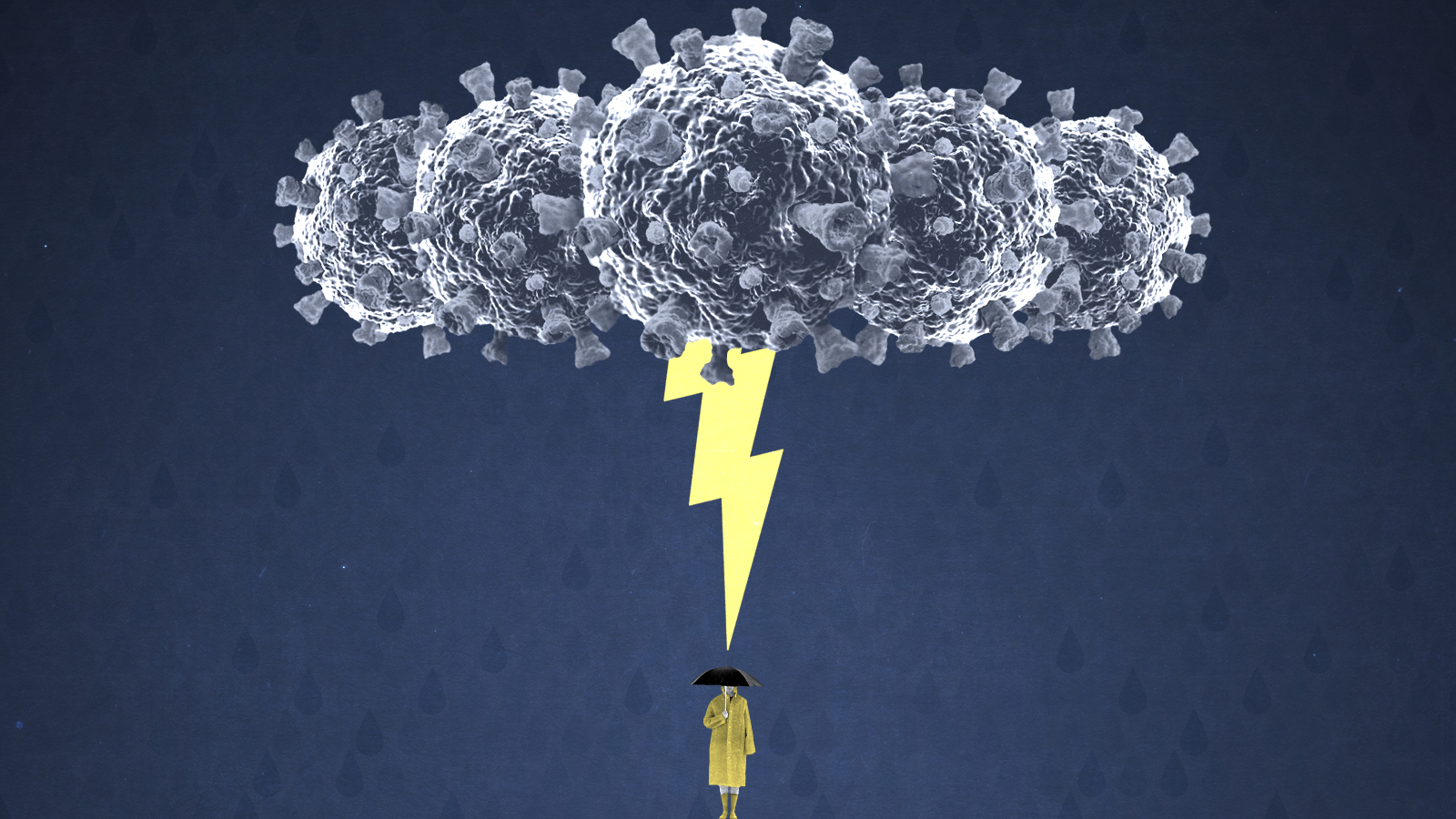

For comparison, the National Safety Council calculates that as of 2019 the average American's lifetime odds of dying in a car accident are about 1 in 107. (That of course includes reckless drivers and very cautious ones, as well as those who drive a lot and those who rarely do, and so forth.) The chance of choking to death on food? One in 2,535. The chance of being killed by a dog? One in 86,781. And the event we often treat as the epitome of an extremely rare incident of terribly bad luck — being killed by a bolt of lightning? The chance of that happening to any random individual, without incorporating other risk factors? One in 138,849.

Which means that, all else being equal, you're roughly seven times more likely to die from being struck by lightning over the course of your lifetime than you were to die from catching COVID-19 (in its current variants) if you were fully vaxxed and boosted in those weeks this past fall. Yes, these are different timescales of risk. But even so, the danger from COVID to vaxxed and boosted people in October and November was simply not a high enough risk to justify the kind of individual behavior we still see around us in many parts of the country every day.

What kind of behavior? My colleague David Faris captured some of it in a recent tweet thread about the decrepit condition of urban life in downtown Chicago. He estimates the commuter train he takes to work is "20 percent pre-pandemic capacity." Bars and restaurants in the economic core of the "loop" are "ghost towns." Homelessness is rampant. Streets are empty and ominous, especially after dark. This isn't primarily because of restrictions imposed from above. It's a product of a million individual decisions to avoid the risk of human interactions.

Yes, we're still in the latter half of the Omicron wave, so some skittishness is understandable. And yes, there are those high rates of daily deaths — even in Chicago.

But who is dying of the virus? Overwhelmingly adults who choose to be unvaccinated. At this point, that's a population of people who have made their own risk assessment, and it is radically different than what's common among people avoiding eating a meal out in the Windy City. Most of the unvaccinated consider it more risky to get the shot than it is to face COVID-19 unprotected. Some of them might prefer to rely on masking instead, but parts of the country with low rates of vaccination also tend to be places with fewer mask mandates and other public health restrictions. So we're looking at a country pretty deeply divided over what's more and less personally dangerous.

I know where I stand. I'm vaxxed and boosted, and I'll gladly get boosted again when that becomes necessary to keep me maximally protected against the virus. I haven't gotten sick yet, and I'd prefer to avoid it if I can. But I'm confident that if I do catch COVID, it will be relatively mild and almost certainly won't kill me. Then again, I don't worry very much about being struck by lightning either.

I hope more people soon make a similar calculation — because that's far more reasonable than either fearing safe and effective vaccines or adapting to a socially constricted life, along with its terrible economic and cultural consequences, as the price of avoiding a risk that's actually incredibly low. I don't want to live in a country where the business districts of our major cities are permanently blighted by depopulation, indigence, and crime — and all because people became too consumed by anxiety to go about their lives as they once did.

This doesn't mean we shouldn't continue to wear masks around the immunocompromised or those at elevated risk of developing more deadly COVID symptoms. Neither does it mean we should refuse to backtrack on restrictions and mandates if a deadlier variant arises. We need, as always, to be flexible.

But for now, being flexible means adjusting to the reality that the vaccines have passed the test. They work. The time to return to normal is now.

CORRECTION: A prior version of this article was unclear about the timescale of relative risks from lightning and COVID-19. It has been corrected. We regret the error.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.