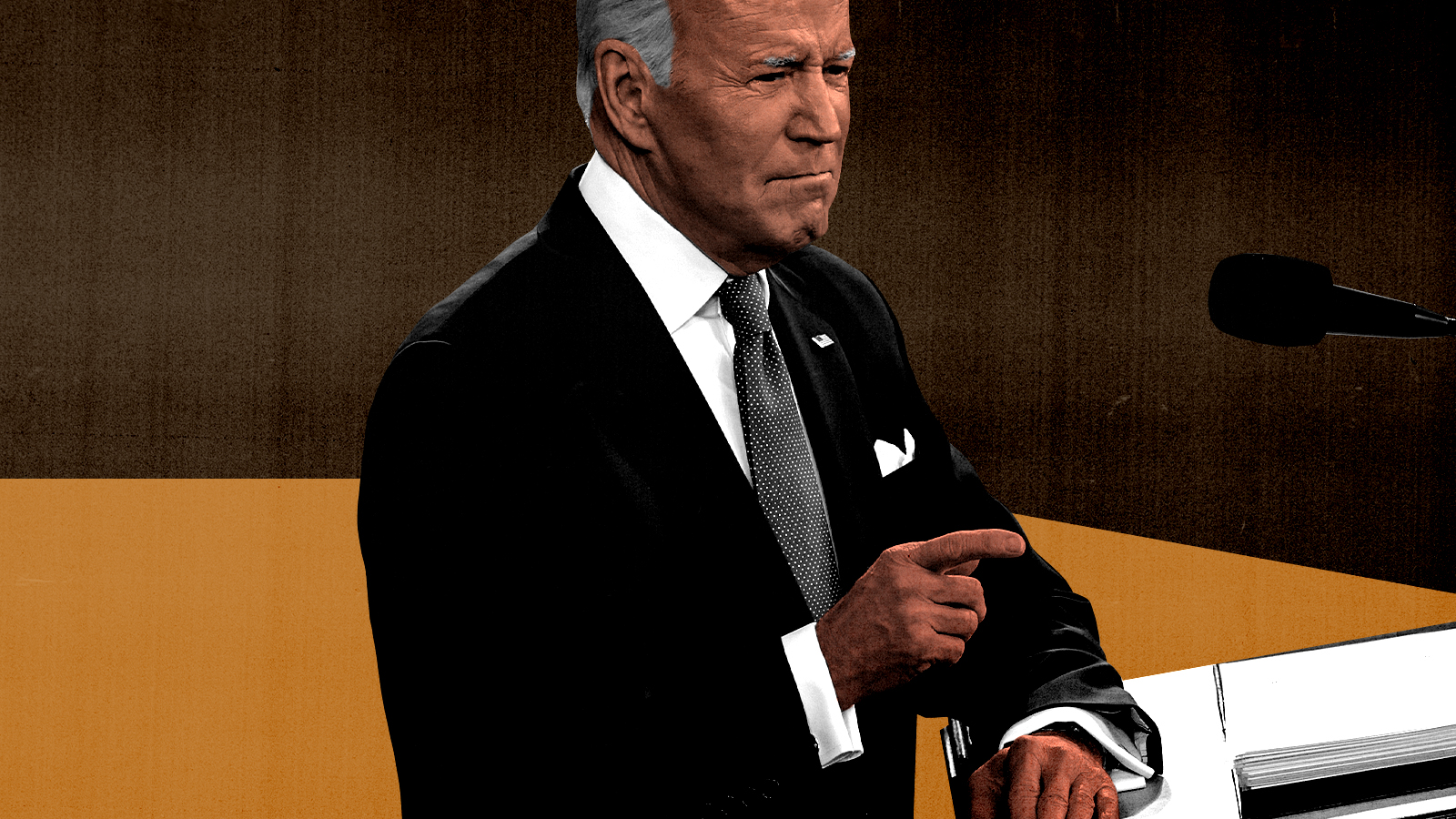

Biden's revealing silence at SOTU

What he didn't say says as much as what he did

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The best way to understand President Biden's State of the Union address is to think about what he didn't say.

There was no mention of Afghanistan, even though troop withdrawals began almost exactly a year before Biden delivered his remarks Tuesday night. There was no mention of his predecessor in the White House or the ongoing congressional investigation into the events of Jan. 6, 2021. Climate change barely came up. Neither did "equity," discrimination, or other aspects of race politics. Biden even managed to announce his nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson without mentioning that, if confirmed, she will be the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court — a historic first that another Democrat facing different political conditions likely would have trumpeted. And there was no tribute to Biden's chief medical adviser, Anthony Fauci, or other public health officials. While Biden continued to warn against the risks of COVID-19, the maskless faces of the audience announced the administration knows the emergency phase of the pandemic is over.

These significant — and presumably deliberate — omissions give a clue about Biden's target audience. He wasn't talking to the progressive wing of his party, for which many of these issues rank close to the top of the agenda. The rift was clear in Rep. Rashida Tlaib's (D-MI) response on behalf of the left, which was one of several unusual post-SOTU speeches by Democrats representing various factions. Characterizing progressives as the president's most loyal supporters, Tlaib called for executive action on student debt, carbon emissions, and other matters Biden seemed reluctant to discuss.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Biden wasn't trying to conciliate the right, though. The opening section on the Ukraine crisis was squarely within the bipartisan consensus that the United States should help Ukraine and punish Russia without playing a direct military role. After that, however, he veered into a wishlist of proposals that would face dim prospects among Republicans even without the threat of inflation. Despite Biden's general avoidance of culture war themes, moreover, no Democratic speech would be complete without a pledge of allegiance to the sexual revolution. In addition to familar struggles over abortion, social conservatives will hear Biden's promise to "our younger transgender Americans" as a threat to extend a radical conception of gender identity to every aspect of federal policy.

No, this was a speech aimed squarely at a group whose importance is disproportionate to their small numbers: voters who supported Biden in 2020 but have been disappointed by his first year in office. Some of those voters are reliable Democrats, but others are true independents, and a few even defected from the Republican Party. As a group, they make up much of the difference between the 51 percent of the popular vote Biden won in 2020 and the roughly 41 percent who approve of the job he's doing now.

Presidential speeches aren't magic spells, and there's nothing Biden could have said that would draw those voters back to him overnight. But both the language and content of his remarks indicate the administration plans to make them its priority as we move toward the 2022 midterms.

That goal explains Biden's repeated invocations of bipartisanship, an ideal the public loves even if pundits and partisan activists don't. It also accounts for promises that could have been borrowed from earlier, more populist generation of Democrats (if not from former President Donald Trump himself), including "buy American" rules for infrastructure projects and pledges to "secure the border."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The biggest problem haunting the speech — and therefore the administration's strategy of courting disappointed Biden voters — isn't merely that these things are easier said than done, as the demise of Biden's Build Back Better agenda indicates. It's that several of Biden's promises are mutually exclusive, however well they perform in polls and focus groups. The tension is particularly stark when it comes to inflation, the top issue for independent voters: Everyone likes the "good paying jobs" Biden promised to bring back from overseas competitors. But few relish the higher prices associated with domestic production.

But the truth is these rhetorical contradictions don't matter very much. State of the Union speeches have little impact on presidential approval, and both historical and contemporary data suggest Democrats face serious losses in the midterm elections no matter what Biden says — or doesn't say.

In 1995, then-President Bill Clinton responded to historic Republican gains by adopting a "triangulation" strategy credited with saving a floundering presidency. It remains to be seen whether Biden can pull off the same trick in policy as well as words.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America