America's Catch-22 in Taiwan and Ukraine

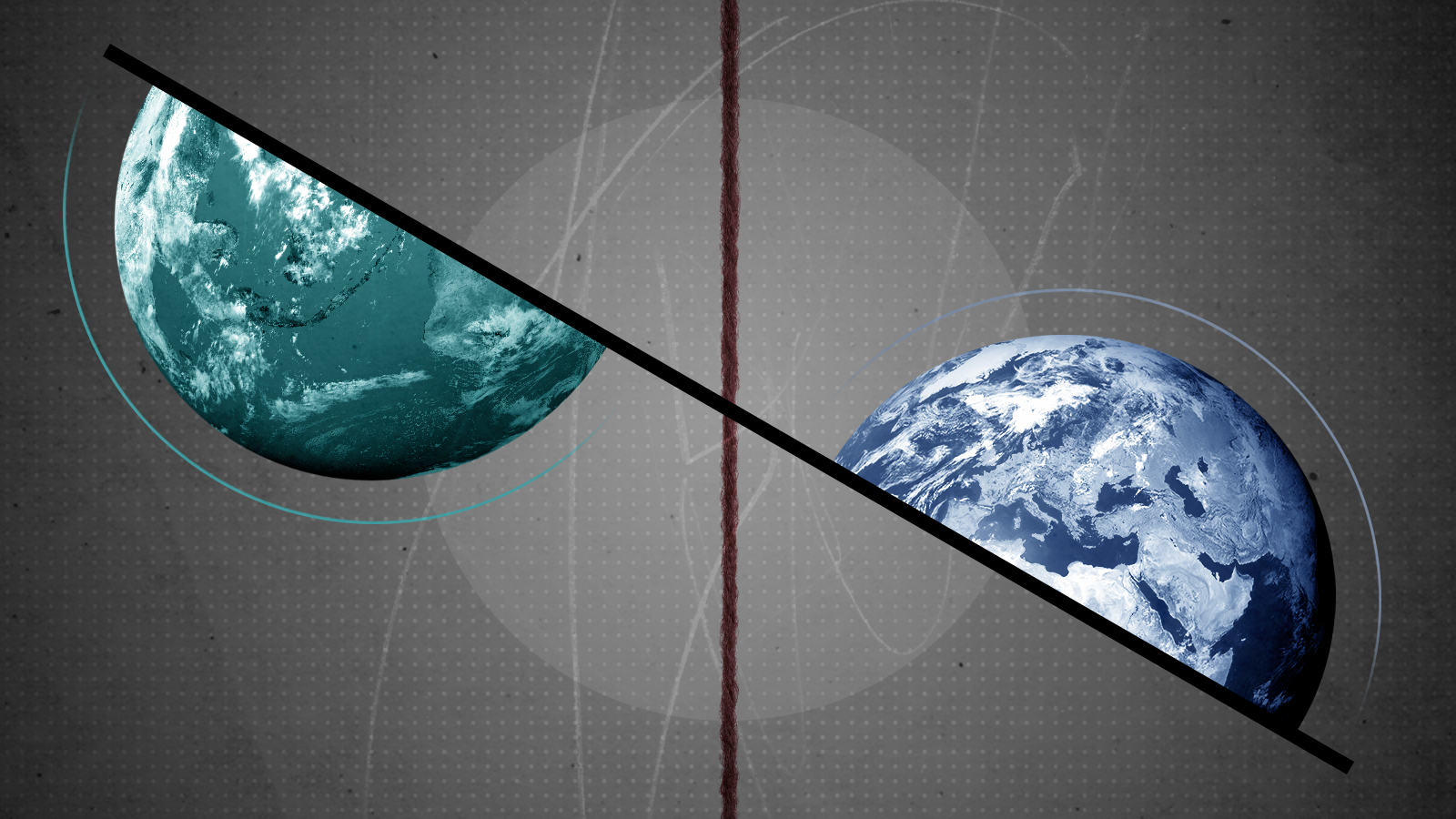

We can put a thumb on the scales of the balance of power, but we can't provide most of the weight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Midway through my undergraduate career, in the fall of 1990, I took a course titled "Russian Imperialism from Ivan the Terrible to the Formation of the U.S.S.R." At the end of the course, the professor turned, uncharacteristically, to current events. The accelerating collapse of Soviet power had already led Lithuania to declare independence, and other Soviet Republics were agitating to join them — including Ukraine. Sensing the hopeful, even heady emotions touching his students half a world away from these events, the professor, though anything but an apologist for the imperialism he studied, addressed the class with a word of caution.

The republic now known as Ukraine, he reminded us, was once the cradle of Russian civilization, and Ukrainian history was tied to Russian history for centuries afterward. Even the 17th-century national hero of Ukrainian independence himself pledged fealty to the Russian Tsar to win Russian support for his uprising against Poland. Founded by Catherine the Great, Odessa was one of the most important cities for imperial Russia's culture and economy; the Crimean port of Sevastopol was home to Russia's Black Sea fleet; and a sizable minority of the population of Ukraine considered themselves simply Russian. Considering all of this, it was inconceivable, he said, that Russia would ever accept the idea of a truly independent Ukraine.

Within a year, of course, Russian President Boris Yeltsin did just that, precipitating the final disintegration of the Soviet Union. But my professor — and President George H. W. Bush, who echoed his sentiments in his infamous "Chicken Kiev" speech — may yet be proved right.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Yeltsin era is now widely viewed within Russia as a shameful period of national humiliation at the hands of an American-led west that must be redeemed by being reversed. Ukrainians themselves may overwhelmingly cherish their independence, and increasingly view Russia as a threat rather than a potential partner. Many Russians, though, refuse to believe them. With Russian troops massing at the Ukrainian border, they may prefer to imagine not only that a war would be easily won, but that a reassertion of Russian dominance would ultimately be welcomed.

These are good reasons for both the United States and its NATO allies to prepare for the possibility of such a war. But are there equally good reasons for us to get involved, either to try to deter a Russian invasion or to repulse one if Moscow attacks regardless of our warnings?

From one perspective, the answer is simple and affirmative. Russia would clearly be the aggressor in any move against Ukraine. Its 2014 seizure of Crimea and the Donbas region was never reversed; if it is allowed to get away with further dismemberment of a sovereign neighbor, the United Nations charter would be exposed as fragile tissue paper and NATO as a paper tiger.

Moreover, how do we imagine China will view American pusillanimity if we let Russia get its way? If we have any hope of stopping a Chinese attack on Taiwan, surely we need to resist Russian moves in Ukraine.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But, of course, a major reason the Biden administration wants a more stable relationship with Russia is precisely to facilitate a pivot to the Pacific to deter Chinese expansion in its near abroad. Conversely, a major reason Russian President Vladimir Putin has forged such a close relationship with China under President Xi Jinping is the recognition that no American government has been willing to respect a Russian sphere of influence in the former Soviet Republics, especially in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, what are we supposed to do if Russia were to invade in defiance of our threats? Going to war with Russia would be madness, but it's unclear whether any response short of war would be adequate to reverse significant Russian military moves. If Russia called our bluff, then, how exactly would that redound to our benefit, in the Western Pacific or anywhere else?

The logic of deterrence, like the logic of the much-ballyhooed "rules-based international order," presumes not only the rational desire for self-preservation on the part of all actors, but that pursuit of conflict with all its inherent uncertainties is, in fact, irrationally self-destructive. That's not always the case, though.

Nothing could be more threatening to the legitimacy of the Russian state, founded as it is on the promise of restoring Russian power and glory, than peacefully accepting Ukraine's drift into the Western orbit. That doesn't mean appeasement would prevent war; it's far more likely that abandoning Ukraine would, indeed, make Russia all the more convinced it can press further. It means that what looks to Washington like deterrence and support for the integrity of a U.N. member's sovereignty looks to Moscow like provocation that must be answered.

The same dynamic is operating across the Taiwan Strait. From one perspective, is not "rational" for Beijing to initiate military action against Taiwan. This would risk pushing China's neighbors more firmly into America's arms, rupturing important economic relationship with Europe, and, not incidentally, destroying much of the economic value of Taiwan itself.

But reunification with Taiwan has been the central aim of Beijing's foreign policy since 1949. Nothing would be more threatening to the PRC's legitimacy than acquiescence in Taiwanese independence. So any move by the United States to bolster the island's ability to achieve and sustain that status is viewed on the mainland as no different from an attack on China itself. This too is a provocation that must be answered.

America's Catch-22, then, is that to sustain the pretense of a rules-based international order, we must oppose any Russian effort to seize more of Ukraine, even though our opposition may provoke precisely the attack it's meant to prevent, and leave us less able to respond to other, arguably more important contingencies. But if we were to reverse ourselves, and abandon Ukraine to subsumption in a Russian sphere of influence to focus more on the Chinese threat, we'd lose our moral basis for objecting to Chinese demands on Taiwan — which, after all, isn't even officially recognized by the United States (or most of the world) as an independent, sovereign state. We'd trip ourselves with our own pivot.

Both Kyiv and Taipei, then, need to be realistic about the part America can play in their own bids to retain their independence and integrity: supportive, perhaps, but not central. We can put a thumb on the scales of the balance of power, but we can't provide most of the weight.

On the other hand, wars launched to subdue proudly independent peoples aren't easy to win. (Just ask Saudi Arabia how their war against poor, outgunned Yemen is going, even with American support.) Neither Putin nor Xi can afford to undermine their own regimes by surrendering their national ambitions — but losing a war against a smaller neighbor would undermine that legitimacy at least as much. The prospect of robust self-defense then, is Ukraine's and Taiwan's only truly reliable deterrent.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trends

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trendsthe week recommends It’s hojicha vs. matcha, plus a whole lot more

-

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probe

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probeSpeed Read Shawn DeRemer, the husband of Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, has been accused of sexual assault

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

‘The mark’s significance is psychological, if that’

‘The mark’s significance is psychological, if that’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?Today’s Big Question Analysts say China’s leader is still focused on reunification

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A running list of the international figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the international figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth The president has grown bolder in flexing executive clemency powers beyond national borders