The complicated problem of banning menthol cigarettes

Banning menthol smokes will save lives, public health officials say. But this is an election year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Biden administration has slammed the brakes on its plan for banning menthol cigarettes, at least for now, The Wall Street Journal said last week. The administration started considering the measure in 2021, hoping it would reduce smoking in young people and people of color — Black and Hispanic smokers are far more likely than white smokers to choose menthols. But it proved more controversial than expected in a public comment period conducted after the Food and Drug Administration finalized the proposal last year.

Opponents of a ban said it could result in racial profiling of Black smokers by police and trigger an illegal market and smuggling. "The cartels would capitalize on being able to smuggle mentholated cigarettes into the U.S.," said Pete Forcelli, a former NYPD officer and retired deputy assistant director at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Cigarette companies lobbied against the change, while public health groups united in favor of it. Further delaying the policy would be "devastating," David Margolius, the director of public health for Cleveland, said to The Washington Post.

The FDA has called its proposed rule against selling the mint-flavored smokes a "critical piece" of President Biden's Cancer Moonshot initiative, said The New York Times. Studies have suggested it could prevent hundreds of thousands of smoking-related deaths over decades. The administration said it still hoped to finalize the ban this year. But it has attracted "historic attention," Xavier Becerra, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, said to the Times. "It's clear that there are still more conversations to have, and that will take significantly more time."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is banning menthols particularly important?

Public health officials have warned that the mint flavor in these cigarettes makes them particularly addictive. It supercharges the influence of nicotine on the brain, and makes the smoke easier to inhale by creating a "cooling sensation," said the Post. Menthols are the only flavored cigarette still on the market. Congress and the Obama administration in 2009 banned other flavored cigarettes, considered enticing for new smokers because they mask tobacco's harsh taste.

In a fact sheet released two years ago, the White House said the ban could be one of the "most significant regulatory actions to-date to limit the death and disease toll of highly addictive and dangerous tobacco products," said the Post. "We're talking about over the next 30 years, probably 600,000 deaths that could be averted," Dr. Robert Califf, the Food and Drug Administration commissioner and a supporter of the ban, said to The New York Times. "This isn't just about curbing smoking rates nationwide," said Jose Cucalon Calderon in The Nevada Independent. "It's about addressing a deadly, cancer-causing product that has been aggressively marketed to minority communities for far too long."

So why delay?

The years of marketing of menthol cigarettes like Newport, Kool and Salem to Black smokers infused the issue with significant racial implications. The proposed ban has divided leaders in the Black community, a key part of Biden's base, with some focusing on the health benefits and others concerned that the fallout could create tensions between police and Black smokers. One thing everyone agrees on is that restrictions on menthol cigarettes would have the biggest impact on Black smokers — about 81% of whom used menthols in 2020, compared with 30% of white smokers and 51% of Hispanic smokers, said The Wall Street Journal, citing its own analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. One study cited by the Journal estimated that a U.S. mentholated cigarette ban would get 1.3 million people to quit smoking within 23 months, including 380,000 Black smokers.

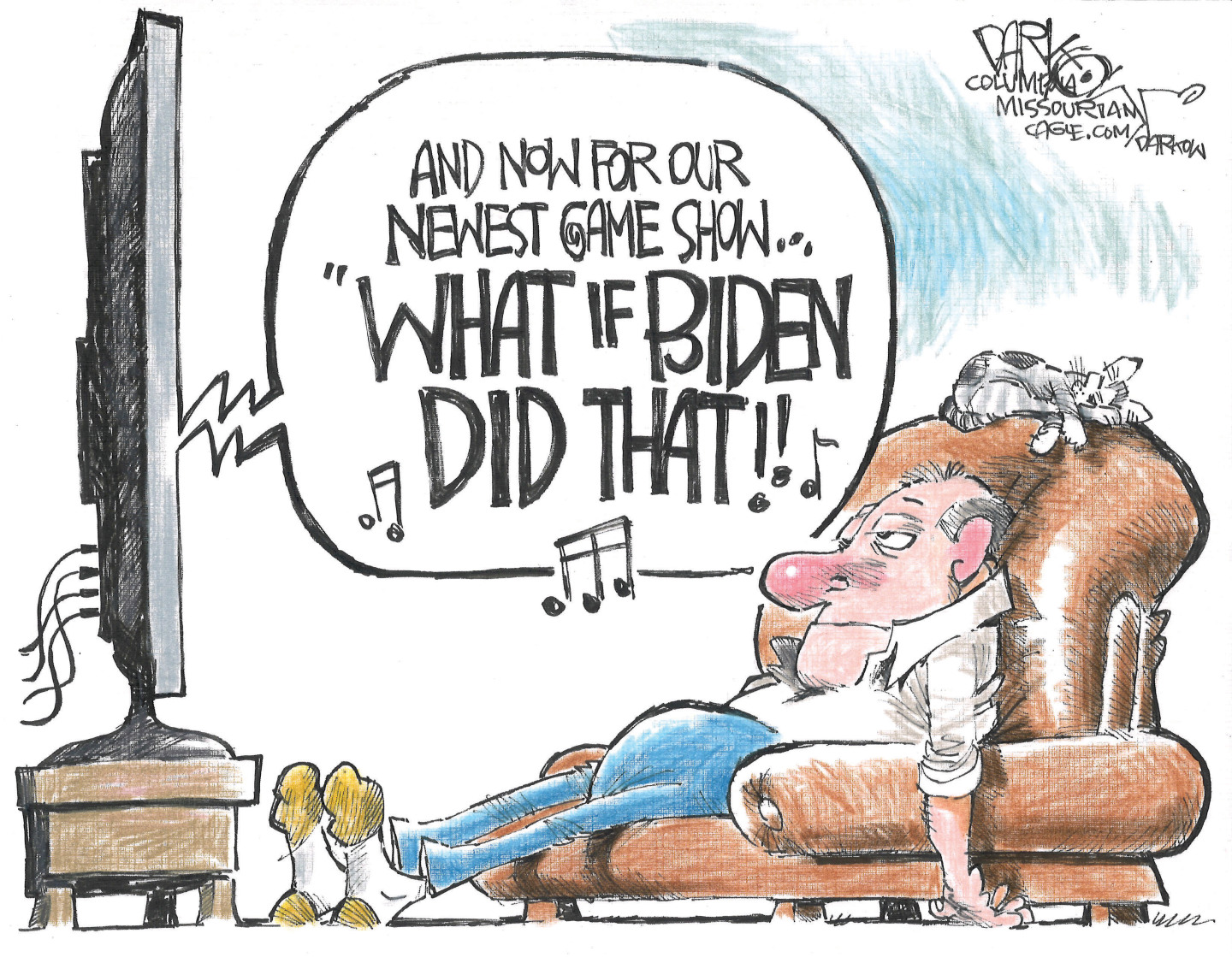

Biden's support among Black voters is weaker than it was four years ago, according to polls. And one survey by a Democratic pollster found that 54% of "'core' Biden voters — defined as minority voters or non-conservative white voters under age 45 — oppose the proposed ban," said Brittany Bernstein at National Review. "The White House appeared to think better of a policy that could anger black voters in an election year," she added. Still, "the decision to delay the ban rather than abandon it means the White House could revive the rule if Biden wins reelection in November," said Adam Cancryn and David Lim at Politico, citing three people familiar with the matter. "But there's little expectation that it will be released during Biden's first term."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda