Scientists have developed a broad-spectrum snake bite antivenom

It works on some of the most dangerous species

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Scientists have sunk their fangs into a panacea for snake bites. The new antivenom can counteract the bite of several deadly species of snake with fewer side effects and easier storage. If made publicly available, it could save thousands of lives each year.

Not just snake oil

Scientists may have developed a snake bite antivenom that can be used for 17 different species of snakes, according to a study published in the journal Nature. The antivenom specifically targets species of snakes in the Elapidae family. There are approximately 360 species of elapids worldwide, and they are “among the deadliest because their venoms contain potent neurotoxins that act rapidly to induce paralysis and respiratory failure,” said Anne Ljungars, a biological engineer at the Technical University of Denmark and a study co-author, to Popular Science. The new antivenom is effective against 17 of 18 elapids found in the African continent, including cobras, mambas and rinkhals.

More than 300,000 snake bites are reported each year in sub-Saharan Africa, along with 7,000 deaths from those bites. While antivenoms have long existed, getting the correct one was dependent on the “victim knowing which species of snake delivered the bite — something that is not always easy to notice in the chaos of the moment,” said The Economist. In addition, the technology to make antivenoms has not changed much since the 1800s.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Current antivenoms are “produced by immunizing horses with snake venom and extracting antibodies from their blood,” resulting in a “large, undefined mixture of antibodies, only a small proportion of which target and neutralize the most dangerous toxins,” said a news release about the study. This creates a product with high levels of variation and potentially serious side effects.

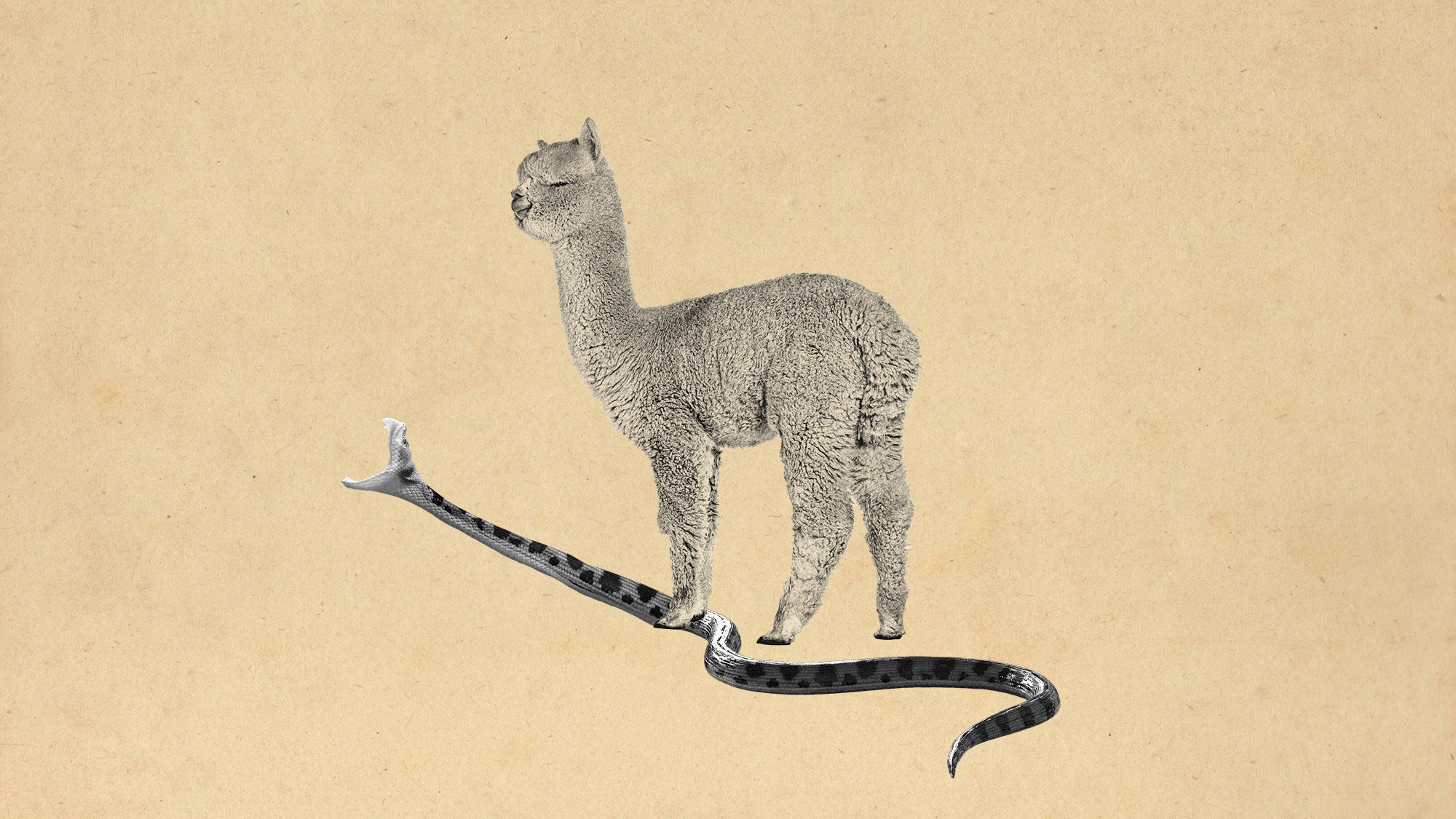

For the new antivenom, researchers opted to use an alpaca and a llama, which have unique immune systems. Camelids, a group these animals are a part of, “naturally produce a special antibody variant known as heavy-chain-only antibodies,” which could be used to engineer nanobodies, said Popular Science. Nanobodies are “smaller and more stable than ordinary antibodies,” said the news release. They can also “bind strongly and precisely to many different similar toxins, which enables the antivenom to neutralize venom from multiple species.”

Once bitten, twice shy

The new multispecies antivenom appears to be safer than the current antivenoms being used. It “almost always prevented tissue death at the injection site,” a problem side effect of many other products that often led to limb amputations, said The Economist. Nanobodies also “penetrate tissue faster and deeper than the larger antibodies in current antivenoms,” said the news release. They can additionally be administered in more remote locations because they can survive being freeze-dried and do not require refrigeration.

While the new antivenom showed promise in mice, it has yet to be tested on humans, and it still needs improvement before it can be made widely available. Despite working for several species, the “effectiveness of the antivenom is limited when it’s given after venom exposure,” said the news release. Furthermore, the venom from certain species was “only partially neutralized.” Still, this study “provides clear evidence of the potential utility of mixtures of nanobodies as a new therapeutic modality for snakebite,” Nicholas Casewell, the director of the Centre for Snakebite Research and Interventions at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and a coauthor of the study, said to The Telegraph.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviews

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviewsTalking Points The guidelines emphasize red meat and full-fat dairy

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic