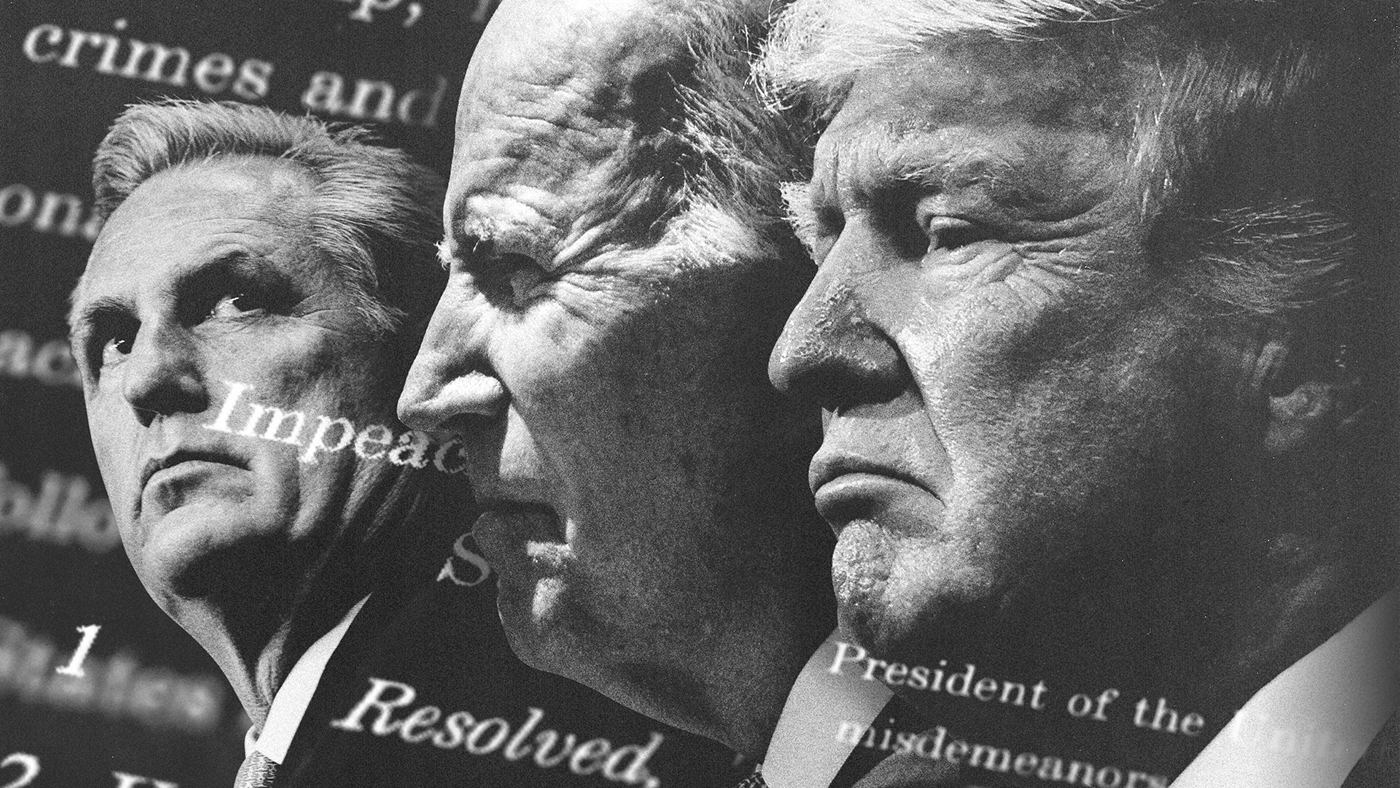

Is the threat of impeachment the new presidential normal?

Impeachment fever: chronic or curable?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

To be the president of the United States is to exist under pressures virtually unimaginable to nearly everyone else on Earth; you control a vast arsenal of weapons capable of destroying the planet many times over; you sit at the top one of of the most powerful, complex economies in history; the lives and wellbeing of hundreds of millions of people depend on your decisions; and to top it all off, you could, theoretically, be fired at any moment. But while impeachment has always been a Damoclean sword hanging over every president's head, it's historically loomed largely as an abstract concern, rather than an acute threat — until recently.

Speaking with Fox News' Sean Hannity this week, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) asserted that his party's ongoing investigations into President Biden and his family's business dealings were "rising to the level of impeachment inquiry" — a statement he defended the following day, comparing the Biden administration to that of disgraced former President Richard Nixon. McCarthy's comments, although conspicuously vague and lacking any concrete timeline, "mark the furthest he's gone on a potential impeachment inquiry," Politico said. And although McCarthy denied any pressure from former President Donald Trump to push forward with impeaching Biden, his comments this week came amid "pressure from the hard right" of his party which has made investigating the president and his family a hallmark of Republicans' narrow congressional majority.

Crucially, McCarthy's escalation — and the GOP's thus far unfounded allegations — against the president exists in the broader context perhaps best stated by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.), who in a recent floor speech linked the conservative effort to impeach Biden with a contemporaneous push to expunge Trump's own impeachment record. To Greene and her allies, the two are inextricably connected, seemingly validating former GOP Rep. Louie Gohmert's 2019 prediction-cum-threat that Republicans would seek political retribution for Trump's impeachment. "We've already got the forms," Gohmert said. "all we have to do is eliminate Donald Trump's name and put Joe Biden's name in there."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With dueling impeachment narratives already saturating the 2024 presidential race, is this formerly rare political last resort our new presidential norm?

What are the commentators saying?

"If impeachment loses its taboo to become just another partisan instrument with implications for elections and fundraising, that would weaken its power as an emergency mechanism," Axios said in 2019, during the first Trump impeachment trial. Whether that process has already begun, however, is unclear. "I do not see this as the beginning of a trend or more likelihood for impeachments in the future," Berkley Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky told the outlet. "I think it is the coincidence of having had a few recent presidents who have committed acts worthy of consideration as impeachable offenses."

"The question going forward, of course, will be whether the Trump impeachment conditions the public to understand impeachment as a tool of normal politics, or whether it retains its exceptional character," Cornell Constitutional Law professor Josh Chafetz told The New York Times that same year. "The Clinton impeachment does not seem to have been enough to make it a tool of normal politics, but maybe this time will be different."

Two years later, The Washington Post appeared to answer Chafetz's question, writing that "the era of perpetual presidential impeachment is probably upon us" after Republicans began calling for Biden to be removed from office — not for his family's business dealings as they are now, but for the U.S. military pullback from Afghanistan. "The trouble with Dems lowering the bar when impeaching Trump over Ukraine is that Biden has certainly now tripped over it himself," former George W. Bush speechwriter Scott Jennings said. "Same elements at play."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Speaking with the New York Times, Republican media strategist Brendan Buck suggested that the potential for an age of perpetual impeachments had less to do with the conduct of any particular president, and more to do with the state of American politics as a whole. "We're in an era where you need to make loud noises and break things in order to get attention," he said in 2021, shortly after Biden assumed the White House. "It doesn't matter what you're breaking — as long as you're creating conflict and appeasing your party, anything goes."

Where do we go from here?

In the short term, a number of high-profile Republicans already have started throwing cold water on the impeachment chatter, with Utah Sen. Mitt Romney noting that "The bar is high crimes and misdemeanors, and that hasn't been alleged at this stage." Fellow Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) said that "the best way to change the presidency is win the election," and even Newt Gingrich, the former GOP House Speaker who led the impeachment effort against former President Bill Clinton sounded skeptical, telling the Washington Post that while "it's a good idea to go to the inquiry stage," going to "impeachment itself is a terrible idea."

That much of the pushback comes from the Senate is perhaps unsurprising given that any impeachment trial against Biden would likely be a non-starter in the Democratic-controlled chamber. Still, Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) seemingly acknowledged the start of a cyclical impeachment chain even as he downplayed the Senate's role in making that decision. "It's getting to be a habit around here, isn't it?," he asked reporters who raised the House's deliberations. "Once you start, it's unfortunate, but what goes around, comes around," he added.

Writing in the Hofstra Law Review in 2020, attorney Erin Daley proposed a series of actions that could potentially break that cycle, returning impeachment from its increased banality to its singular status as a last resort. Suggesting a "new standard for impeachment," Daley highlights statutory reforms to strengthen the legislative branch's ability to conduct genuine impeachment inquiries, while giving more clear oversight to the judicial branch as "a tool that could help Democrats and Republicans alike" while also preventing a "future Republican-led Congress from conducting a similar polarizing impeachment against a more liberal president."

"It is impossible to comport with Framer intent when Congress uses impeachment as a political weapon and the president completely disregards checks and balances," Daley concluded. "Polarization has ruined the transparency and legitimacy of impeachments, and for now, Congress should recognize that '[i]mpeachment needs the legitimacy that the courts can provide.'"

We may indeed be entering an era of perpetual impeachment, but there are, it seems, exit ramps — if we want them.

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.

-

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern

-

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 February

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?Today’s Big Question Since the ceasefire agreement in October, the situation in Gaza is still ‘precarious’, with the path to peace facing ‘many obstacles’