The History of Ink

The first use of ink can be traced back 40,000 years, discovers James Morris

Mankind's use of ink colouration to communicate images and writing has a long history. The oldest cave paintings known were created more than 40,000 years ago in El Castillo in northern Spain, and Sulawesi in Indonesia. This wasn’t figurative imagery, but you have to move forward between only 8,000 and 10,000 years for the first cave painting portraying the natural world, in the Chauvet Cave in France. In this era, the ink used was based on red, ochre and black manganese dyes, but also plant sap and animal blood. Since then, the material of ink and its characteristics has changed incredibly. In this feature, we trace the progress through the major milestones to the present day, where advanced inks allow office printers such as HP's Officejet Pro X series to produce perfect output in less than a second per page.

Words and pictures

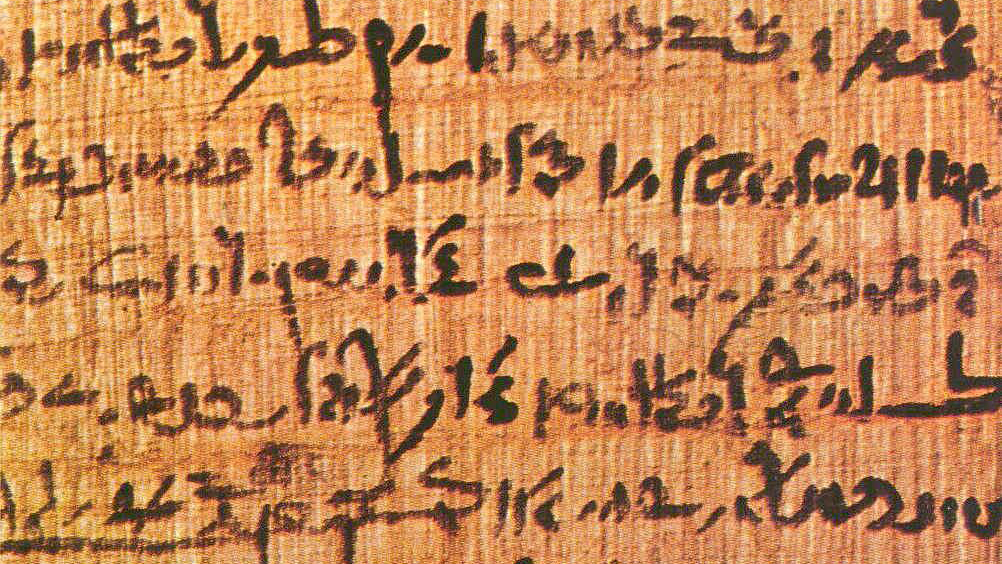

The use of ink remained exclusively for artistic use for more than 35,000 years. Writing emerged in the Sumerian region of Mesopotamia around 3,200 BCE, and it was produced either by creating impressions in clay or through carving into other surfaces. The development of writing with ink took place around 2,500 BCE, at approximately the same time in both Egypt and China. For their pigment, the inks used a type of carbon called lamp black, which is created by partially burning tar with a little vegetable oil. The pigment was suspended in gum or other glue, to ensure it adhered to the host surface. There was a strong need for the writing to endure, and the carbon ensured this. The advent of ink-based writing also went hand in hand with the use of the first paper in the form of papyrus, made from the pith of the papyrus plant, a type of sedge.

However, papyrus was fragile, it couldn’t be folded, and was susceptible to both dry and wet conditions. So parchment, made from animal skin, began to replace papyrus at the start of around the 1st century BCE. Just before this, India ink had been developed from earlier inks. This was composed of carbon black, lamp black, and charred bones (called bone black), combined together with animal glue to create a block, which would then be re-liquefied by the addition of water, usually via a brush. India ink was used in China from the 4th century BCE, and was also the type of ink employed for writing the Dead Sea Scrolls, although the latter relied on red cinnabar (mercury ore) as its base rather than carbon.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Carbon-based inks such as India ink are pigmented, and they have great durability, so light and chemicals don't cause fading. However, they also require paper that’s absorbent, because they will flake off of non-absorbent surfaces such as parchment, and can also aggregate into flakes, which would make the ink inconsistent. This means they’re not ideal for every use or writing surface. As a result, around the 8th century, inks using chemical precipitation were developed, with the first being iron gall ink based on tannic acid and iron salt bound by resin. This could be used with a quill pen and parchment or vellum, making this the standard mode of writing from the 12th century to the 19th century.

Woodblock and movable-type printing

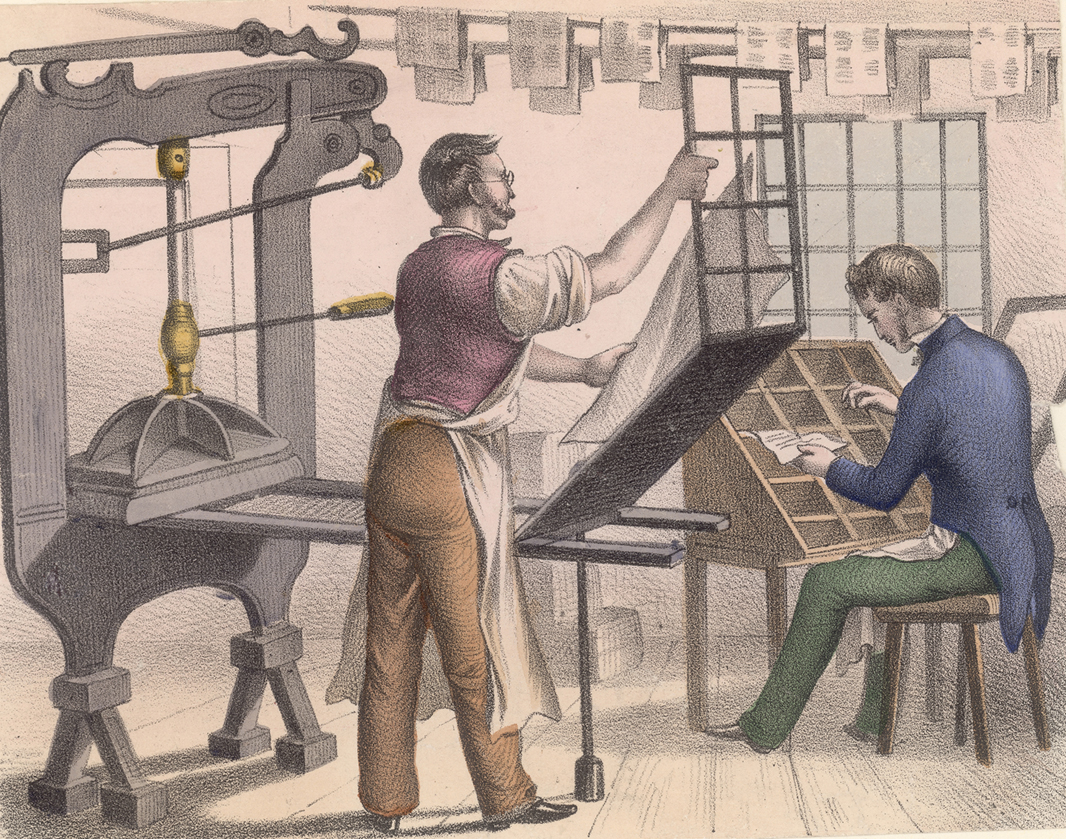

All through this era, writing text using ink was primarily performed by hand, although printing with woodblocks began to grow in importance from around the 2nd century AD in China. However, a huge amount of labour was required to create the wooden printing blocks, and any mistakes would probably result in a block being discarded. This focus on human labour made text documents extremely expensive, and only available to a choice few who could afford them. But a potential solution arrived in the creation of movable-type printing by Bi Sheng in 1040 AD, which used ceramic materials and also wood, although the latter was later abandoned. By the 12th century, bronze movable type was being used in China, and this was soon emulated in Korea, with many printed books being produced.

Europe came relatively late, and independently of China, to this revolution. Between 1436 and 1450, Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith, developed techniques to cast letters using a hand mould. This made the mass production of letters cheap enough to be economically viable for a complete book. The printing press Gutenberg built in Mainz in 1457 was joined by the development of 110 more presses across Europe by 1480. To go with the metal type of the printing press, Gutenberg also had to formulate a new kind of oil-based ink that was more suitable for adhering to metal. This ink was carbon-based, but also contained copper, lead and titanium. It has been described as more similar to a varnish than ink.

Print for mass communication

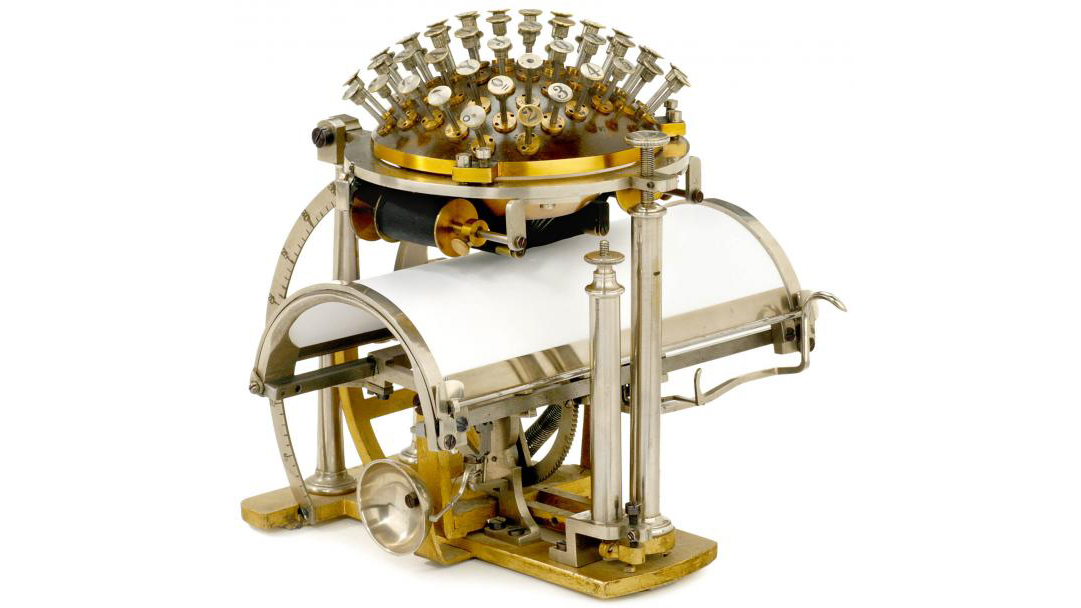

The arrival of the printing press made the written word far more widespread than ever before, and its use for printing bibles has been cited as a major influence of the Reformation, since more people could read the word of God themselves rather than rely on books owned only by religious leaders. But printing was still very much in the hands of an elite few. It wasn't until the advent of the typewriter in the 1860s that the ability to print became viable for business communication, and this required yet another development in ink. The Hansen Writing Ball typewriter was invented in 1865 and went into mass production in 1870, followed by models from a number of other manufacturers. In most cases, typewriters relied on an ink-soaked ribbon of cloth. The pigmented ink was designed to stay moist on the ribbon through the addition of castor oil, but it would dry once it contacted paper. Later designs, in particular IBM's Selectric typewriter, used ribbons of pigment-coated polymer tape. In both cases, the impact of the type transfers the ink to the paper.

Inkjet and laser printers

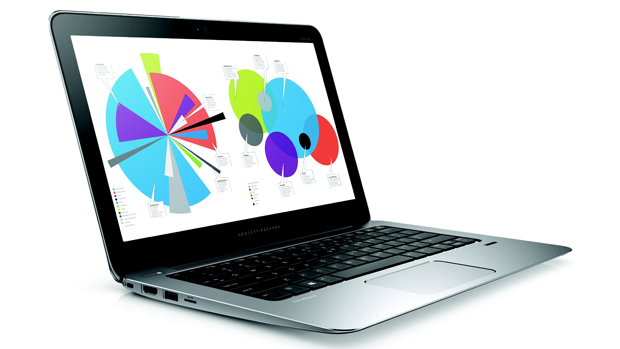

Computerised printing has led to yet more development in the types of ink. The daisywheel printers of the late 1960s and 1970s used a similar impact system to a typewriter, and the dot-matrix printer generalised this by providing an array of metal rods that recreated the shape of the letter. The laser printer, however, uses an electrostatic system to transfer its ink. The toner used needs to be attracted to the charged areas of the imaging drum. Originally this was made from a combination of carbon powder mixed with iron oxide and sugar, but later a polymer mix was used instead. The fuser melts the toner particles so they bond with the paper.

Companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Epson and Canon first developed Inkjet printers in the 1970s. Alongside solvent, aqueous, UV-curable and dye-sublimation inks were also produced. With an inkjet, minute particles of ink are sprayed onto the paper, directed by magnetised plates. The dots are smaller than the diameter of a human hair. The solvent from the ink dye soaks into the paper so the colour remains. The makeup of modern inkjet ink is extremely sophisticated. It needs to contain a detergent to prevent the nozzle of the printer from clogging, and also a dispersing agent so that the pigments don't cluster, and instead spread evenly. It also needs to dry quickly and resist fading. Most inkjets use water-based dye inks, but HP's Officejet Pro X inks are pigmented. This provides excellent fade and water resistance, although we’ll have to wait another 40,000 years to find out if the print-outs can last as long as mankind's first ever use of ink back in the caves of northern Spain and Indonesia.

For more advice on transforming your business, visit HP BusinessNow

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

How has Iran been preparing for war?

How has Iran been preparing for war?Today’s Big Question As the Iran war enters its second week, Tehran turns to — and adjusts — longstanding plans to defend itself

-

How to make friends as an adult

How to make friends as an adultThe Week Recommends Finding new friendships in adulthood is hard, but not impossible

-

AI fears are giving rise to ‘HALO trading’

AI fears are giving rise to ‘HALO trading’The explainer Lower tech, higher value

-

The executive style guide

The executive style guidefeature Want to stand out from the business crowd? Here's all the kit you need.

-

Seven ways to reduce stress in your office

Seven ways to reduce stress in your officefeature You can’t completely remove it from your life, but there are some easy ways to relieve it…

-

Hello Fresh: The transformation begins

Hello Fresh: The transformation beginsfeature New offices and a wealth of new IT from HP for Hello Fresh.

-

Controversial Colour Branding Decisions

Controversial Colour Branding Decisionsfeature Scott King and Russell Jones from Condiment Junkie discuss how some brands have decided to swim against the tide with their colour choices.

-

How do you design a computer?

How do you design a computer?feature Lead designer of HP, Chad Paris, explains how new computers are brought to life

-

The story of print

The story of printfeature Printing has come a long way since its origins. Here we map out the story of print past, present and future

-

Tribal Colours

Tribal Coloursfeature Colour has been used for centuries as a means to communicate where we belong, finds Stuart Andrews

-

The Colour of Branding

The Colour of Brandingfeature James Morris explains why companies choose their corporate colour schemes, and what they mean.