Tribal Colours

Colour has been used for centuries as a means to communicate where we belong, finds Stuart Andrews

Colour can be powerful. Various hues and tones have different psychological effects; they can change how we feel, how we behave and what we buy. Colour can also affect how we see other people – pushing us to see them as friendly, professional or trustworthy. It can make them seem more attractive, more authoritative or worthy of respect. Colours can even make us see ourselves differently. What's true of individuals is even more so when we come together in groups. As we adopt a social mentality, colour cuts through to a primitive function of our brain, becoming a kind of shorthand that tells us that we belong to a group, and that other people belong with us.

Group mentality

It's all a question of social identity, or the way that we as human beings reinforce our own self-image by joining groups with which we share similar characteristics, values or ideas. We hone in on those similarities – often exaggerating them – and look for things that differentiate our group from other groups. Here, colour can play a vital role. In groups where we don’t look the same or even sound the same, colour instantly tells us who belongs. Put on a shirt, wave a flag or paint your face a certain colour, and everyone knows that you’re part of the group. Has it always been this way? Well, while there's little surviving evidence to tell us how our oldest cultures used colour, contemporary tribal cultures continue to use it as a means of identifying members. Native American tribes still have specific tribal colours that are used in ceremonies, art, clothing and everyday life, and while they might share some of these colours with neighbouring tribes, one tribe’s set will differ from that of another.

Tribal dress

Across Africa, many tribal societies still adopt specific colours. In the Pokot tribe of Kenya, for example, men will wear coloured clay caps to show which clan they belong to, while the Masai regard red as a sacred colour, and use it extensively in their tunic – the shuka – and their beadwork. The Naga tribes of the Indian/Burmese border tell each other apart by the colour and design of the shawls they wear, while the Dao tribes of Vietnam use brightly coloured headscarves, tunics and trousers, often in vibrant reds and blues. Colour played just as big a part in the ancient world. While we think of the ancient Greeks in plain white chiton tunics, bright colours were actually favoured, and would have had determined group identity or rank. The Spartans, for instance, are thought to have been fond of a deep crimson red, which the warlike people saw as an aggressive, masculine colour – also ideal for hiding wounds or splattered blood.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At the height of the Roman Empire, Chariot Racing was the Empire's biggest sport. Drivers competed within four factions – red, white, green and blue – with fans adopting the colours of their favourite faction in their apparel. As the Roman Empire waned and moved eastwards to Constantinople – modern Istanbul – the dominant blue and green factions became influential in military, political and theological matters. The intense rivalry of the hippodrome crossed over and grew worse, finally erupting into street violence. In 501AD, the greens ambushed the blues in Constantinople's amphitheatre, massacring nearly 3,000.

The battle lines

Although tribes might join to become nations, tribal thinking never disappears entirely. As Europe reached the middle ages, colour became a key way of demonstrating which faction you belonged to. The knights of the 12th century went into battle wearing colours on their shields, and these evolved into complex systems of heraldry. Knights and lords wore the colours of their family or those of their military orders, and as time went on these were adopted by their retinue, and by the men who served under them. Knights at a tournament might wear a lady's colours, showing their allegiance to the lady and her family through sporting a pennant or garment on their lance or armoured sleeve.

In the heat of battle, colour played a very practical role. At a glance, you knew who was on your side, and who you were meant to be attacking. There's a reason that we still know the standards armies carry into battle as “colours” – a brightly coloured flag has an instant impact that no design on its own could match. In 1483, Richard III banned the wearing of coloured livery jackets except for those in his own colour: red. At the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, many of the troops on Richard's side would have been clad in the king's crimson colours, with some of those on the Tudor side clad in the family’s green and white. It was the same story in Feudal Japan. The bright colours used in Samurai standards were mirrored in the lacquered armour the elite warriors wore, with each faction garbed in different combinations of blacks, reds and blues or yellows, greens and whites.

Uniform choices

By the 18th century, coloured military uniform was a must. Muskets and gunpowder smoke made the battlefield confusing, and it was vital that commanders could recognise their own units and distinguish them from the foe. The bright-red coats of the British and Danish troops made them a visible target, but also distanced them from the blue-coated Polish, French and Prussians, the white or light-grey Saxon, Spanish and Austrian troops, or the Russians in their dark green.

Modern warfare made brightly coloured uniforms a bad idea, but colours still bind many groups together. Think of political movements; the reds of communism and the labour movement, the blacks associated with fascist ideologies, the greens of environmentalism. Each is used to designate membership of a group, and belief in an ideal. Go back to the 1860s, and you have Garibaldi and his army of red shirts, fighting off the Bourbons in Naples and marching towards Rome. Fast-forward more than a 150 years, and in Thailand we have two opposing political groups in coloured shirts, with the red shirts supporting the ruling party and the yellow shirts the opposition.

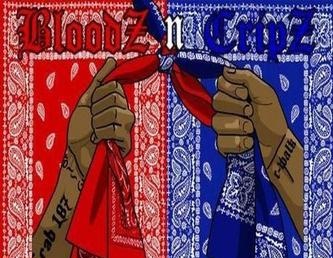

Tribal thinking still comes through in the way that Los Angeles-based street gangs use them to show gang affiliation. Bloods wear red, Crips wear blue and associated gangs garb themselves accordingly. Gangs also use colour to show opposition. For example, the Texan street gang La Primera wears white, while its deadly rivals, the Cholos, wears black.

Sporting culture

Closer to home, remember today's football fans. As the sport became more popular in the 19th century, players wore coloured caps or sashes to help them tell the two teams apart. Caps eventually became jerseys and full kits, and colour became a crucial part of the early teams’ identities. Fans adopted their team’s colours, and wore them as a mark of their loyalty. Now, wearing your team's colours is a sign of your commitment; something that identifies who you are and which club you support. What Manchester City fan would be caught dead wearing red when their team was playing United? Colour is an instant signifier even there.

Tribes and football teams aren’t as far apart as you might think, and colour plays the same role in both. It can bring groups together and also push people apart, but it always helps us communicate who we are and what we stand for. In this way, colour can help us transform the world.

For more advice on transforming your business, visit HP BusinessNow

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The executive style guide

The executive style guidefeature Want to stand out from the business crowd? Here's all the kit you need.

-

Seven ways to reduce stress in your office

Seven ways to reduce stress in your officefeature You can’t completely remove it from your life, but there are some easy ways to relieve it…

-

Hello Fresh: The transformation begins

Hello Fresh: The transformation beginsfeature New offices and a wealth of new IT from HP for Hello Fresh.

-

Controversial Colour Branding Decisions

Controversial Colour Branding Decisionsfeature Scott King and Russell Jones from Condiment Junkie discuss how some brands have decided to swim against the tide with their colour choices.

-

How do you design a computer?

How do you design a computer?feature Lead designer of HP, Chad Paris, explains how new computers are brought to life

-

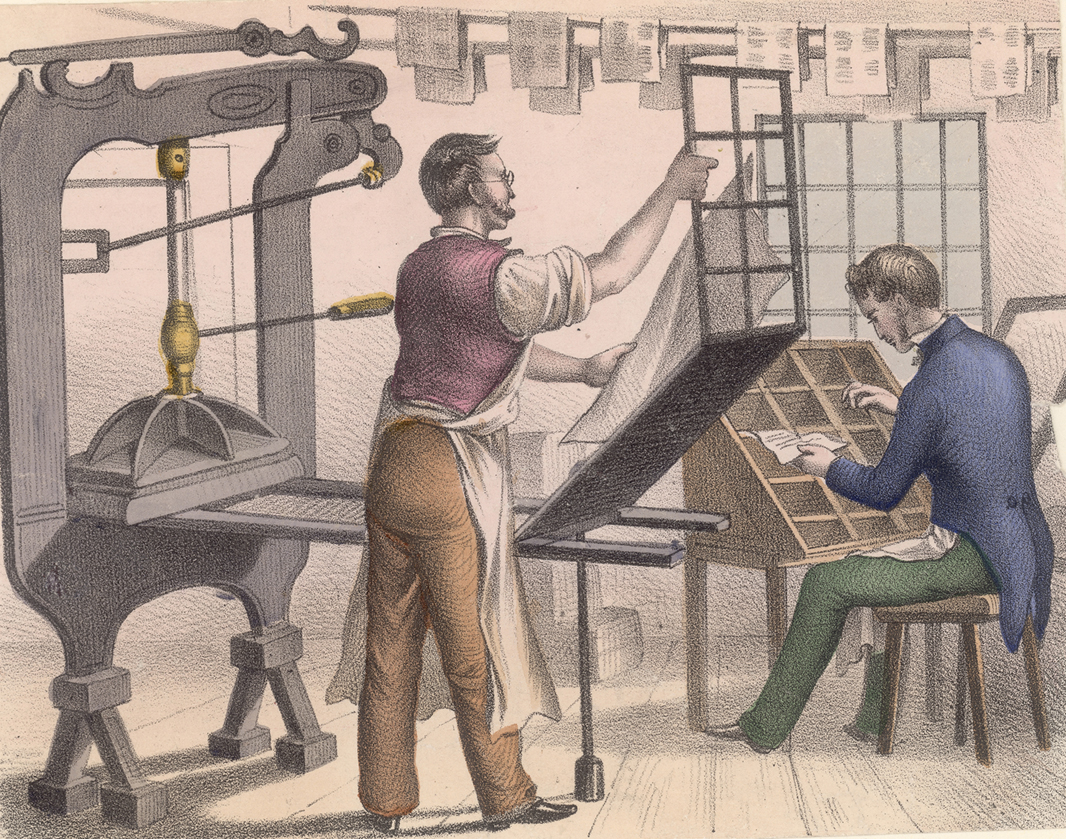

The story of print

The story of printfeature Printing has come a long way since its origins. Here we map out the story of print past, present and future

-

The Colour of Branding

The Colour of Brandingfeature James Morris explains why companies choose their corporate colour schemes, and what they mean.

-

Does colour exist?

Does colour exist?feature Red and yellow and pink and green – scientists say that these are all just figments of your imagination