Has populism had its day in the UK?

Trump-style politics may be on the wane in the UK but it has cast a long shadow over Westminster

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Boris Johnson, Nicola Sturgeon and Jeremy Corbyn – the three populist politicians who led their parties at the last general election now find their careers and legacies in tatters.

A “damning” report by MPs published today found that Johnson deliberately and repeatedly misled Parliament over lockdown parties, said the BBC.

The former PM, who led the Conservative Party to a “landslide election victory” just three years ago, is now in the ignominious position of being the “first former prime minister to have been found to have deliberately misled Parliament”. The report by the Commons Privileges Committee “demolishes Boris Johnson’s character and conduct”, said the BBC’s political editor Chris Mason.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Its publication followed the arrest on Sunday of Nicola Sturgeon, former leader of the SNP and Scotland’s longest-serving first minister. She was questioned by police investigating allegations of financial misconduct, before later being released without charge.

And Jeremy Corbyn, once Labour leader, has been banned from standing as an MP for the party at the next election over a protracted antisemitism row, with his once influential left-wing allies marginalised in the party.

What did the papers say?

Britain’s style of modern populism has “always been just a bit rubbish”, said Sherelle Jacobs in The Daily Telegraph. It has been dogged by a “distinct lack of leadership vision”, she argued. “Johnsonianism was a greased puddle of incoherent opportunism – all pork barrel promises, green grandstanding and Brexit bluffs,” said Jacobs. Sturgeon’s pro-EU nationalism, meanwhile, was a “contradiction in terms”.

There is an “inauthenticity” to Britain’s brand of populism, said Jacobs. It was always “unclear” whether Johnson “really believed” in Brexit, and SNP politicians “may rail against the remote Westminster elite, but they reside within their own hermetically sealed bubble of NGO professionals, academics and career campaigners”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The cases of Johnson, Sturgeon and Corbyn may all vary, said Robert Shrimsley in the Financial Times (FT), but there are “common threads” in their stories that offer warnings about the “dangers of populism and political monomania”.

What marks their leadership reigns is “the primacy of a revolutionary zeal that refuses to be tempered by economic and political realities”, alongside “fanatical supporters and the concentration of power in a purist vanguard”.

Neither Johnson nor Corbyn became leaders “because their parties believed they would be good at governing”, but rather “as vehicles for a faction’s goals”. Their personal failings were “ignored or dismissed as smears” as their “flaws mattered less than the cause”.

The troubles facing the SNP are more “complex”, but Sturgeon’s current problems spring, in part, from her “fierce control” of the party: “Sturgeon was no figurehead,” wrote Shrimsley, “but the astute and undisputed chief.”

While Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer may have, to some extent, “restored normal service” in British politics, “what was true before can be true again”, warned Shrimsley. “In Westminster, activists have seen that the most effective way to advance a hardline ideology is to enter and take control of a party.”

What next?

Those who believe in a pluralist democracy should be cheered by the investigation into the SNP’s alleged financial misconduct, as well as the “quiet courage” of the Conservative MPs on the Privileges Committee. “It’s the system, however ill, eventually pushing back,” said Andrew Marr in The New Statesman.

But “politics never stops”, he said, and there will one day be “more populists” in British politics. Starmer, however, could soon have the opportunity to make the 2024 election “not the moment of another, possibly short-lived, Labour interruption in British politics but the beginning of a long, left-liberal hegemony, as long-lasting as the Conservative one has been”. That could be achieved through voting reform, suggested Marr.

The Labour Party has shown support for implementing a proportional voting system, and recent polling indicates that a majority of Labour voters and party members also back this change. But there is a risk that another referendum, this time on PR, “would revive, even energise, the right-wing English populism which has taken such a knock in recent days”, added Marr.

A Conservative ‘divorce’?

British Conservatism has been an “uneasy coalition” for many years, with the 2016 split between Brexiters and Remainers evolving into something more like a split between populists and realists”, said Gaby Hinsliff in The Guardian.

With the two factions “barely capable of pulling together in power, it’s hard to imagine them coexisting blissfully amid the bitter acrimony of defeat”, should Labour win the next general election, she added.

Indeed, some Conservatives are now “privately pinning their hopes” that a Labour minority government will introduce a PR-type system, under which “a breakaway party could finally become viable”. But should there be a Conservative “divorce” there is a question over who retains the established Conservative brand name and who is “deemed the splinter party”.

If the Conservative Party is beaten in the next election, will its members interpret that “as a sign that they somehow still hadn’t moved far enough right, or as a warning that the country had had enough of populists?”

Recent political history suggests that it would be “brave to bet on a defeated party in 2024 jumping to the obvious conclusion”, said Hinsliff.

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?Today’s Big Question Women lead the resistance to Trump’s deportations

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

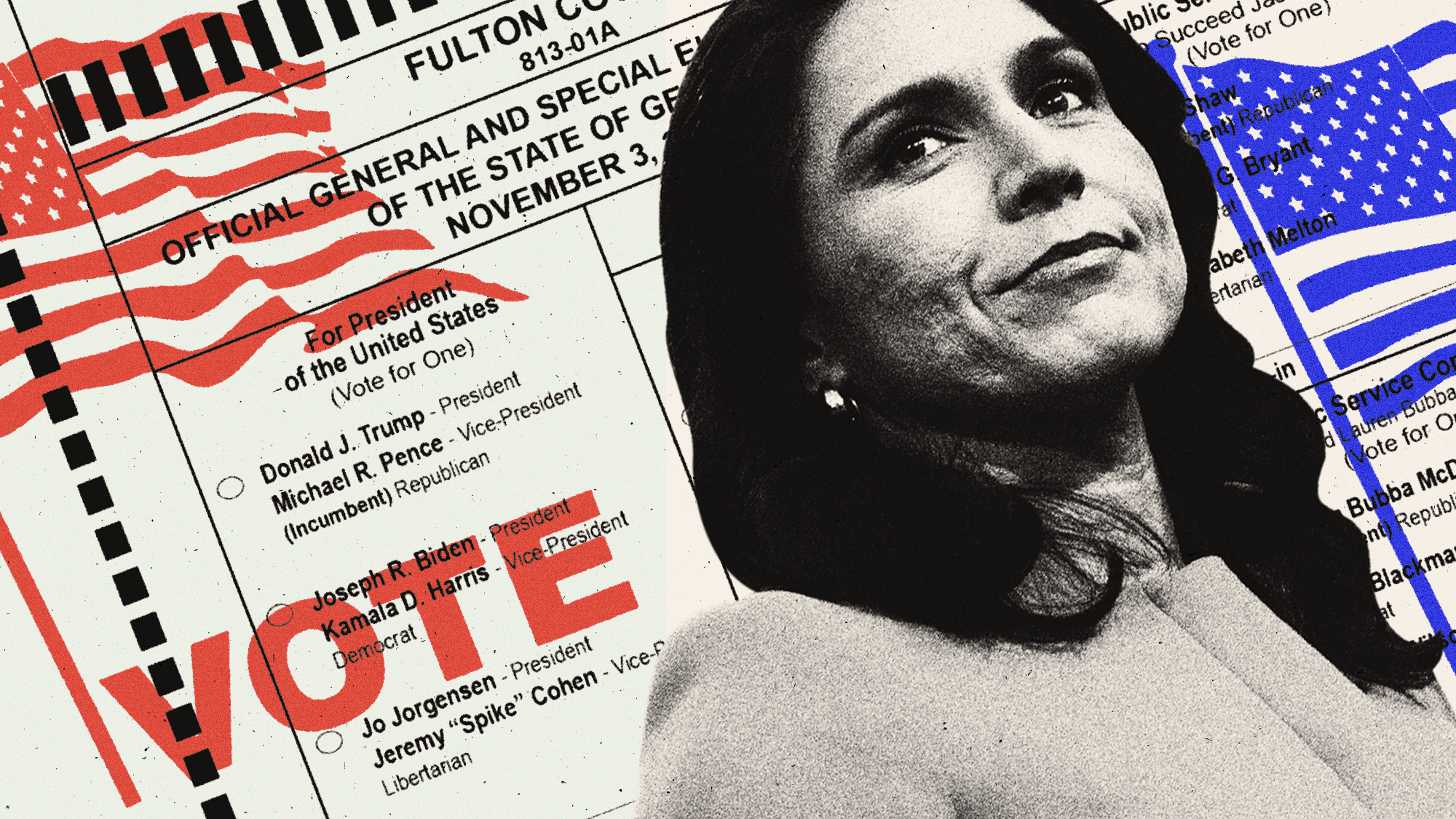

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?Today's Big Question Trump has never conceded his loss that year

-

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?Today’s Big Question Centrists, lefty activists also debate abolishing ICE

-

Three consequences from the Jenrick defection

Three consequences from the Jenrick defectionThe Explainer Both Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage may claim victory, but Jenrick’s move has ‘all-but ended the chances of any deal to unite the British right’

-

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?Today’s Big Question Trump claims control over crude reserves, but challenges loom