The risk of noise-induced hearing loss

Experts believe young people can protect themselves from the dangers of noise-induced hearing loss

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Samuel Couth, research associate at the University of Manchester, explains how loud is too loud when it comes to hearing damage.

A recent study published in BMJ Global Health has estimated that over one billion people worldwide aged 12-34 years could be at risk of noise-induced hearing loss. The systematic review and meta-analysis found that 24% of young people engage in unsafe listening practices when using a personal listening device (such as headphones), while an estimated 48% do so at least once a month by attending noisy events (such as concerts or clubs).

In this study, “unsafe listening” relates to not only how loud the noise is, but for how long a person is exposed. A person’s maximum recommended noise exposure dose is no more than 85 dB (decibels) for eight hours a day. This is roughly as loud as city traffic or a busy restaurant.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For every three decibel increase in noise, this equates to a doubling in sound energy – meaning that the exposure time should be halved (known as the “three dB rule”). So if the sound in a typical concert is around 105 dB, a person would exceed their daily noise dose within approximately five minutes of being there. Headphones and earphones can reach similar levels when put up to maximum volume.

Frequently engaging in unsafe listening practices can lead to permanent hearing loss. Fortunately, there are many easy things you can do to lower this risk.

Knowing your risk

It’s important to note this study only estimates the number of young people who could be at risk of hearing loss – it does not report on how many people have already developed hearing loss due to unsafe listening practices. The authors acknowledge that more well-designed studies are needed to better understand the effects of recreational noise exposure across the lifespan.

However, we do know from studies on other types of noise just how harmful it can be to hearing. For example, studies investigating the effects of occupational noise exposure (such as from loud construction machinery) have shown that it’s linked with high levels of hearing loss and tinnitus (a ringing or buzzing sensation in the ears). In such jobs, average daily noise exposures can exceed 100 dB. Similar problems have also been found in the music industry, with approximately 64% of pop-rock musicians reporting to have hearing loss.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In theory, the delicate parts of the inner ear are equally as susceptible to damage from loud music as they are from noisy machinery and power tools. Regular exposure to high levels of noise can destroy the sensory hair cells in the ear that are responsible for amplifying everyday sounds. Damage to them is irreversible, meaning that noise-induced hearing loss is permanent.

Early symptoms of hearing damage can include muffled hearing (like having wool in your ears) and tinnitus – both of which can be common after exposure to loud noise. But even though these symptoms may disappear within a couple of hours or days, it has been suggested that these symptoms could still be initial warning signs of more insidious damage to parts of the inner ear.

While these early signs of hearing loss might be nothing more than a minor annoyance when you’re young, as hearing loss worsens it can have a major impact on quality of life. Some studies have even shown it’s associated with depression and cognitive decline later in life. This is why it’s vital to look after your hearing even when you’re young.

Protecting your hearing

The first and most effective way to reduce the risk of hearing loss is to eliminate the noise at its source. In other words, turn the volume down. This is easy to do with personal listening devices, since many smartphones are already wired to alert you when you’ve been listening for too long at a high volume.

But turning the volume down can be harder to do when attending loud events. To protect yourself, limit your exposure – either by moving away from the sound source (avoid standing in front of loudspeakers) or taking a break in a quiet space every 15 minutes or so. It’s also recommended you give your ears at least 16 hours rest if you spend around two hours in a 100 dB environment, such as a club or concert.

You could also use hearing protection devices (such as earplugs) at noisy events. These are usually considered as a last line of defence, but may be the best option if you are unable to limit your exposure – or don’t want to.

Disposable foam earplugs will help to prevent noise-induced hearing loss if worn correctly. But they aren’t really designed for listening to music and can make music sound muffled, which puts many people off using them. Musicians’ earplugs are a better solution, as these are designed to evenly balance noise reduction across all frequencies, which preserves the quality of the music.

Even if you follow these measures to protect your hearing, it’s still advisable to get your hearing checked by an audiologist. While there’s no rule on how regularly you should get your hearing checked when you’re young, some audiologists recommend having at least one test done in your 20s to serve as a baseline, and then to get retested approximately every five years to monitor any changes.

But if you’re regularly exposed to noise or already have some hearing loss, it’s advised you get your hearing checked more frequently. You should also contact your GP immediately if you notice any sudden changes in your hearing.

Samuel Couth, Research Associate, Hearing Science, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Jenin and the endless cycle of Palestinian displacement

Jenin and the endless cycle of Palestinian displacementfeature Refugee camp at the heart of a struggle around demographics, displacement and mobility

-

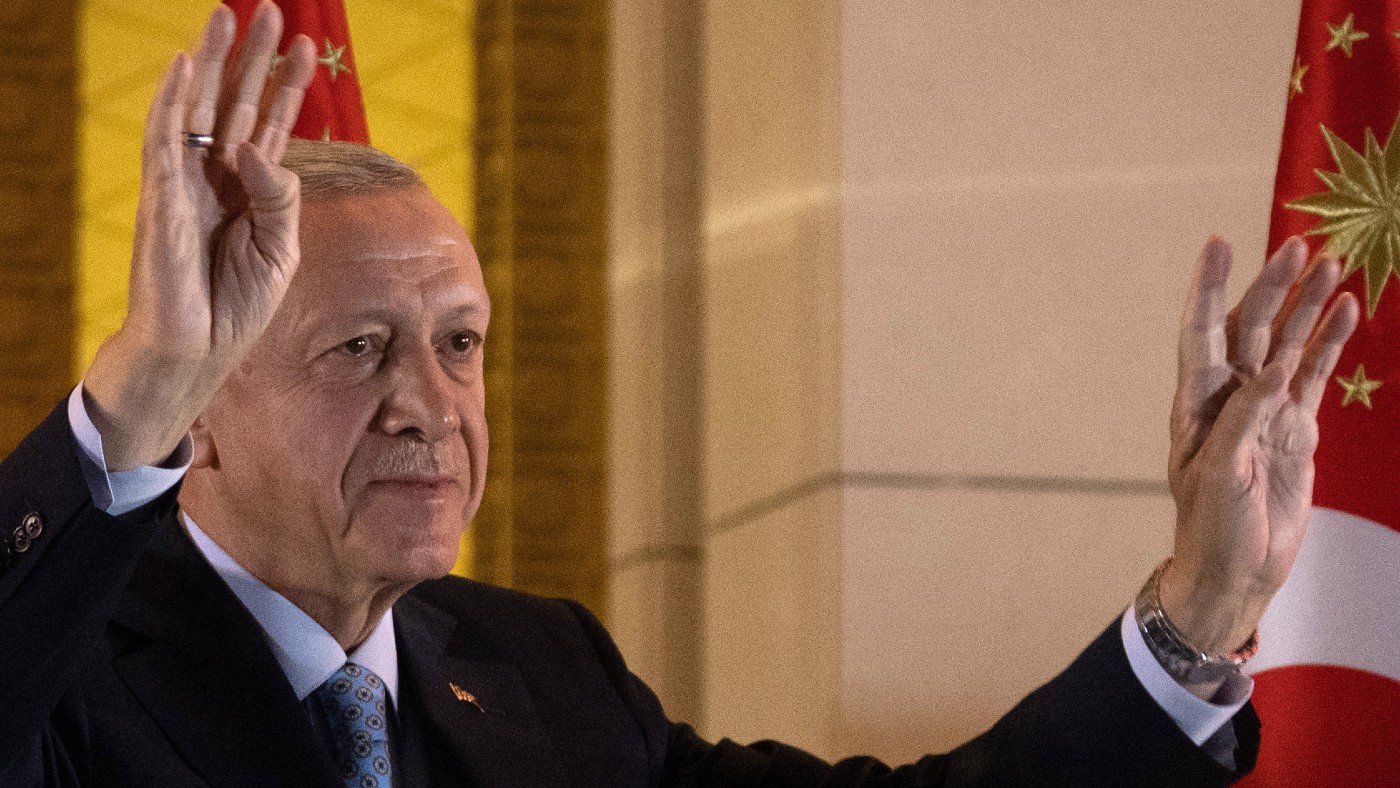

How Erdogan held onto power in Turkey and what this means for the country’s future

How Erdogan held onto power in Turkey and what this means for the country’s futurefeature Staunch support from religious voters and control of the media ensured another five-year term for Turkish president

-

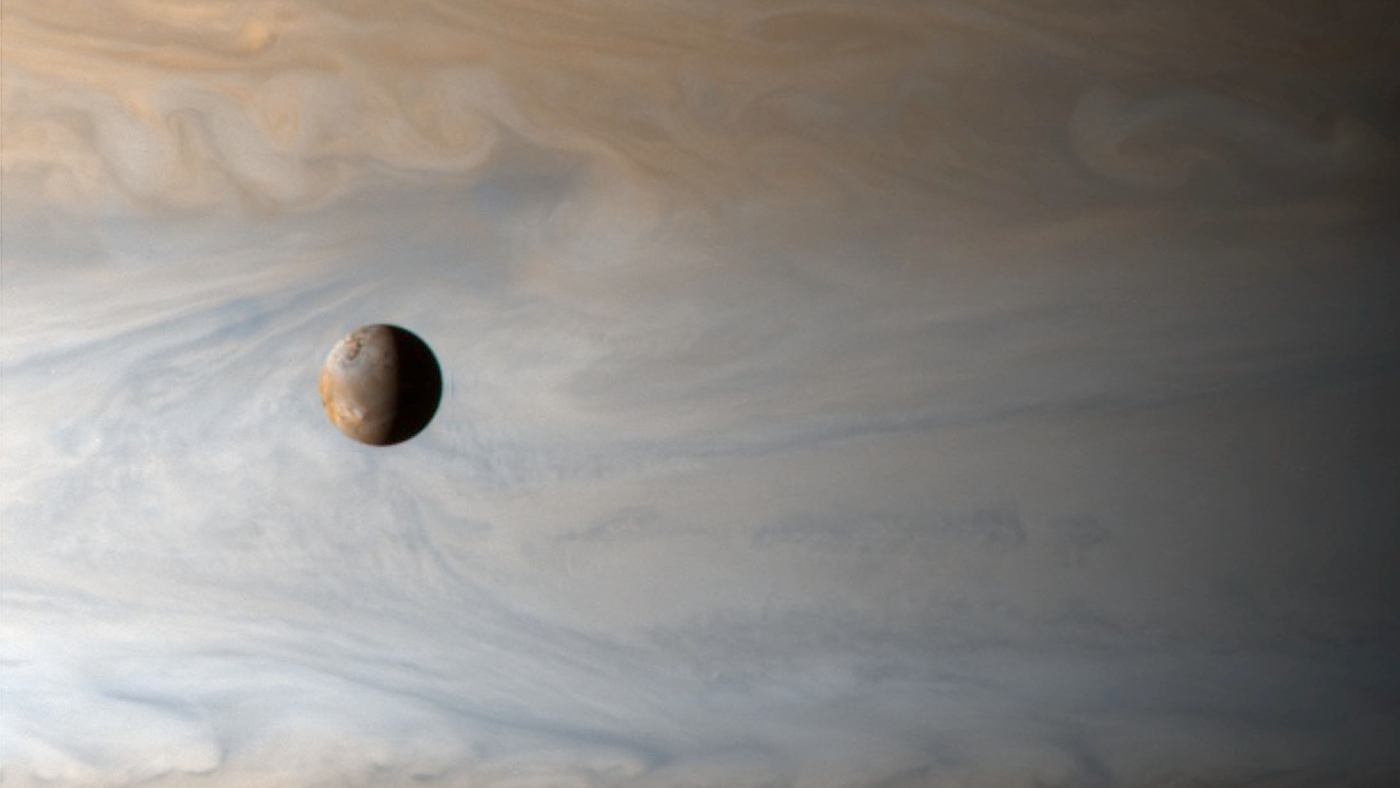

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moons

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moonsfeature Three of Jupiter’s moons are home to large, underground oceans that could support life

-

Lula and the world: what to expect from new Brazilian foreign policy

Lula and the world: what to expect from new Brazilian foreign policyfeature As Brazil’s new president kicks off his third term, foreign policy will be a tool for building his own domestic political legitimacy

-

Swimming pools vs. wild swimming: which is worse for germs?

Swimming pools vs. wild swimming: which is worse for germs?feature A microbiologist explores where’s cleanest for a dip: swimming pools, or rivers, lakes, canals and the sea?

-

Why it’s time for the UK to introduce mandatory training for new dog owners

Why it’s time for the UK to introduce mandatory training for new dog ownersfeature A recent rise in fatal dog attacks shows the system is letting down both dogs and humans

-

Why humans haven’t evolved to cope with cold northern climates

Why humans haven’t evolved to cope with cold northern climatesfeature Intricate cultural solutions to the challenges of life have seen humans thrive in every part of the globe

-

What Harry & Meghan reveals about the Duchess of Sussex’s reputation within the royal family

What Harry & Meghan reveals about the Duchess of Sussex’s reputation within the royal familyfeature New Netflix documentary shines a light on the British monarchy’s relationship with the patriarchy and whiteness