Is British Summer Time still fit for purpose?

BTS, which began last Sunday, has been observed for more than a century

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The concept of daylight saving was first proposed in 1895 by the New Zealand entomologist George Hudson, who wanted more daylight to allow him to collect insects after work. But it was William Willett who successfully championed the idea.

Willett, a prosperous builder, had a eureka moment while out riding in Kent early on a summer’s morning. In 1907, he published a pamphlet, The Waste of Daylight, which noted that in summer “the Sun shines upon the land for several hours each day while we are asleep”, and yet there “remains only a brief spell of declining daylight” after work, in which to pursue leisure activities (a keen golfer, he disliked cutting short his round at dusk).

Rather impractically, he proposed moving the clocks forward by 80 minutes, in 20-minute weekly steps, on Sundays in April, and doing the reverse in September. He campaigned vigorously; but Parliament rejected the idea in 1909, and Willett was to die of flu in 1915 before his plan was adopted.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When was his proposal adopted?

Germany was the first country to do so – deciding, in April 1916, to put the clocks forward in order to save electricity used for lighting and thus boost production during the First World War; Britain followed suit a few weeks later, using Greenwich Mean Time in the winter but moving to GMT+1, or British Summer Time (BST), during the summer months. The US followed in March 1918.

In Britain, the move initially caused confusion and opposition, though the nation has mostly stuck to the same system since 1916. In America, the confusion was longer-lasting. Daylight saving was cancelled after the War because of pressure from the farm lobby, but some states kept it, resulting in a patchwork of multiple different time zones – until in 1966, Congress passed the Uniform Time Act, promoting six months of standard and six of daylight saving. Today, daylight saving is used in about 70 countries, affecting more than one billion people.

And what benefits does it bring?

It certainly helps us to enjoy long summer evenings. Beyond that, says Michael Downing, author of a book on the subject, “opponents and supporters of daylight saving are still not sure exactly what it does”.

Studies suggest it increases physical activity – TV ratings for the evenings drop when the clocks go forward in spring. It certainly reduces electricity used on lighting – though in the US it has been suggested that these savings are offset by extra energy consumed in leisure activities. It seems to reduce traffic accidents, which rise after dark, and is popular with business, because longer evenings encourage people to shop.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What are the downsides?

The actual changing of the clocks is inconvenient and unpopular, and has tangibly negative effects. Scientists in Denmark who studied 185,419 people diagnosed with depression found that the condition soared by 11% when the clocks went back in autumn, caused by the disruption of body clocks and the suddenly shortened evenings.

Other studies have found that the risk of heart attacks, strokes and traffic accidents grows immediately after the clocks go forward in the spring, and judges are more likely to dole out harsh sentences then, presumably owing to the loss of an hour of sleep. A 2019 YouGov poll found that people in the UK were moderately in favour of keeping BST, by 44% to 39%. But a clear majority of Britons (59%) would like to remain permanently on summer time.

So why don’t we do that?

Britain tried it between October 1968 and October 1971. Harold Wilson’s government adopted GMT+1 all year round, or British Standard Time, as an experiment. The Home Office reported that it caused a substantial drop in road fatalities in the evening and a slight increase in the morning, as well as considerable savings in electricity and an increase in outdoor sports.

Official polls found that it was supported by 50% of the population and opposed by 41%, but it was unpopular in Scotland, where in midwinter the Sun didn’t rise until as late as 10am, meaning that children walked to school in the dark.

Business and tourism were in favour of British Standard Time; farmers, the construction industry and other outdoor workers with early starts, such as postmen, objected to having to work for hours in the dark. On a free vote in 1970, the House of Commons voted by 366 to 81 in favour of returning to the old system.

What positions have other nations taken?

Most nations that aren’t near the equator observe daylight saving in some form. The major exceptions are India, Russia and China. But whatever position a nation takes, it seems to remain controversial in some quarters. Russia instituted permanent daylight saving in 2011, then rejected it altogether in 2014.

In 2019, the European Parliament voted to do away with daylight saving, though the proposal has yet to be approved by the European Council. In the US, by contrast, a bipartisan group of senators unanimously voted through the Sunshine Protection Act of 2021, which would make year-round daylight saving time the law of the land; neither President Biden nor the House of Representatives has yet approved the measure.

Is any change likely in the UK?

In 2010, a Private Member’s Bill was proposed calling for year-round daylight saving. Alex Salmond called it an attempt to “plunge Scotland into morning darkness”. It was filibustered out of Parliament; Jacob Rees-Mogg added a wrecking amendment giving Somerset its own time zone.

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents is still campaigning for year-round BST, which it estimates would reduce road deaths by 70 per year and would have a host of other benefits, including a reduction in crime, which increases in the hours of darkness.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 years

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 yearsfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?Talking Point Goverment under pressure to prohibit breed blamed for series of fatal attacks

-

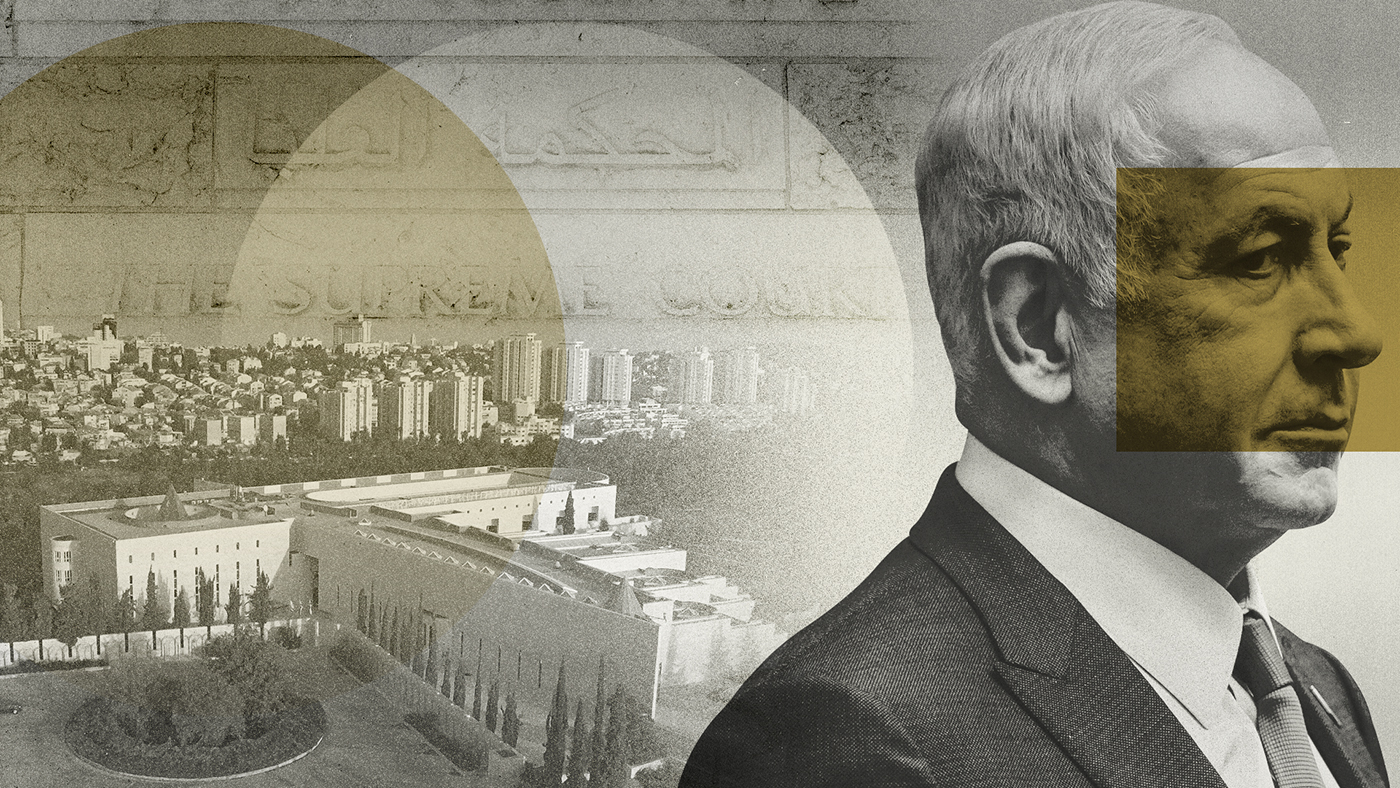

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wife

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wifefeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders

-

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled haven

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled havenfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classes

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classesfeature Reports of the death of the Chinese economy may be greatly exaggerated say analysts

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some