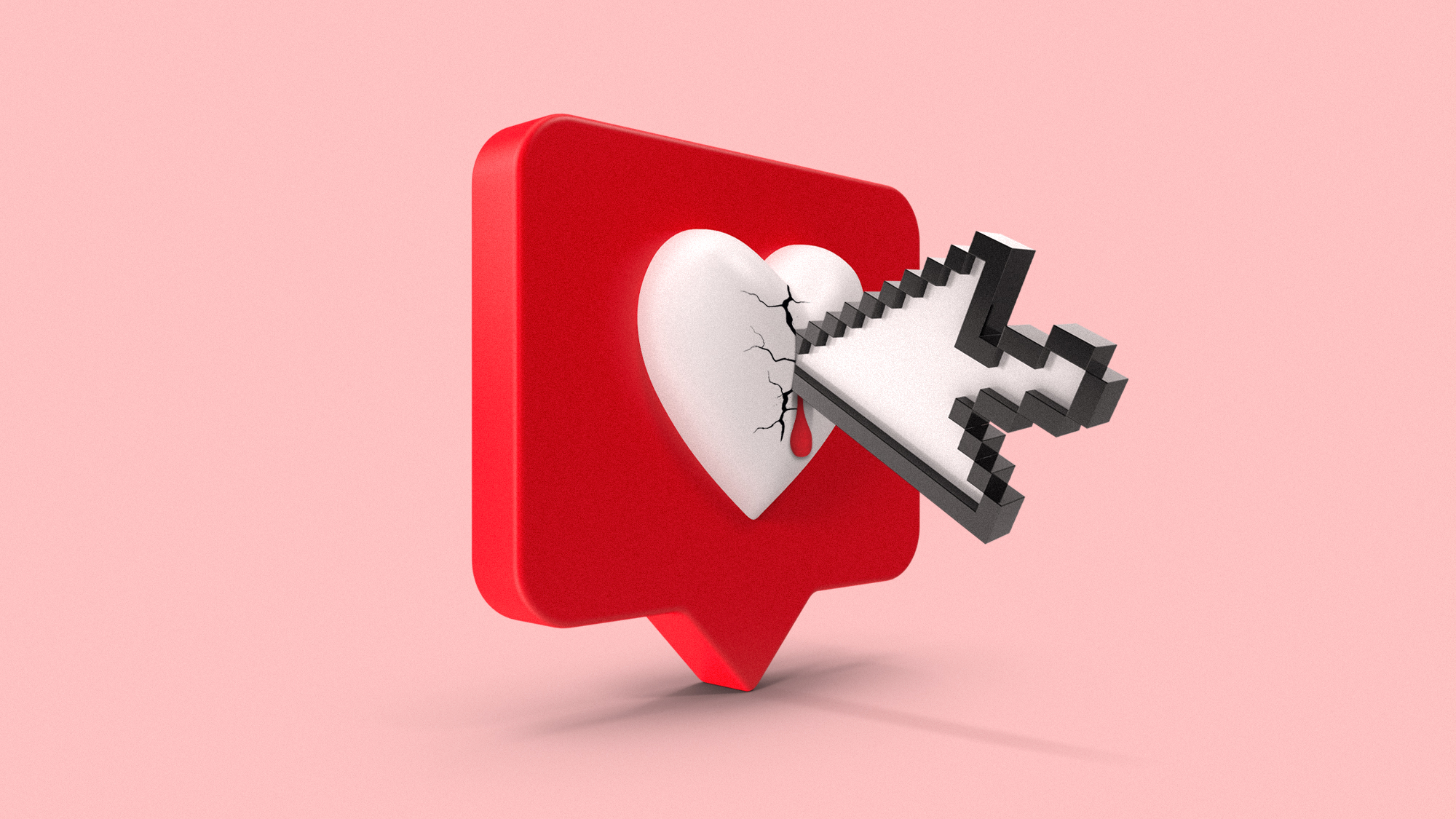

Does big tech monetise adolescent pain?

Father of Molly Russell, 14, said she had been sucked into a ‘vortex’ of ever darker material

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“It’s the rueful half-smile that breaks my heart,” said Judith Woods in The Daily Telegraph. Ambushed by a camera-wielding parent outside their home, a younger child would have beamed or scowled.

But Molly Russell offers that “oh-go-on-then-if-you-must” expression that “every self-aware teen gives her soppy dad”. It is an “intimation of adulthood” – the willingness to make “brief accommodations” to spare other people’s feelings, and get on with the day.

But Molly will not reach adulthood. In November 2017, the 14-year-old was found dead in her bedroom, having spent months viewing online content linked to depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide. Some of it romanticised self-harm. Much of it was so graphic, bleak and violent that a psychiatrist told the inquest into Molly’s death that he’d been “unable to sleep well” for weeks after seeing it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A ‘vortex’ of dark material

Not only had a child been able to access this distressing material, many of the posts had been provided to Molly, unasked, by Instagram and Pinterest’s “recommendation engines”, said John Naughton in The Observer. Thus the teenager – described by her father as a “positive” young woman, who seemed to be having only “normal teenage mood swings” – had been sucked into a “vortex” of ever darker material.

At the inquest, an executive from Meta, Instagram’s owner, denied that the 2,100 depression, self-harm or suicide-linked posts that Molly had liked or saved in the six months before her death were unsafe for children, and said that it was good for them to be able to share their feelings. But in what may be a world first, north London’s senior coroner ruled last week that Molly had died from an act of self-harm while suffering from depression – and “the negative effects of online content”.

Potential impact of Online Safety Bill

There are some who hope that the Government’s Online Safety Bill will make the internet safer for our children, said Hugo Rifkind in The Times. But this legislation keeps being delayed because trying to ban harmful content leads ministers into a “thicket of debate about free speech and censorship”. It’s complex; it’s also a red herring.

Teenagers have always sought out dark material, and found it. The difference now is the manner in which it is delivered to them. To read one sad post may be cathartic – it’s being bombarded with them that is dangerous. This is what we should tackle: not the content itself, but Big Tech’s “relentless monetising” of people’s absorption in content about self-harm, or “anything else”. “It’s a system, a design, a business model.” And the tech giants can fix it, if we make them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?Feature Possibilities include to curry favor with Trump or to try to end financial losses

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question A trial will determine whether Meta and YouTube designed addictive products

-

Silicon Valley: Worker activism makes a comeback

Silicon Valley: Worker activism makes a comebackFeature The ICE shootings in Minneapolis horrified big tech workers

-

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you now

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you nowFeature AI can take notes—and give advice

-

Is social media over?

Is social media over?Today’s Big Question We may look back on 2025 as the moment social media jumped the shark

-

The dark side of how kids are using AI

The dark side of how kids are using AIUnder the Radar Chatbots have become places where children ‘talk about violence, explore romantic or sexual roleplay, and seek advice when no adult is watching’

-

Metaverse: Zuckerberg quits his virtual obsession

Metaverse: Zuckerberg quits his virtual obsessionFeature The tech mogul’s vision for virtual worlds inhabited by millions of users was clearly a flop