Will economic growth solve the UK’s problems?

Sceptics say growing the economy favours the rich while Liz Truss claims everyone benefits

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

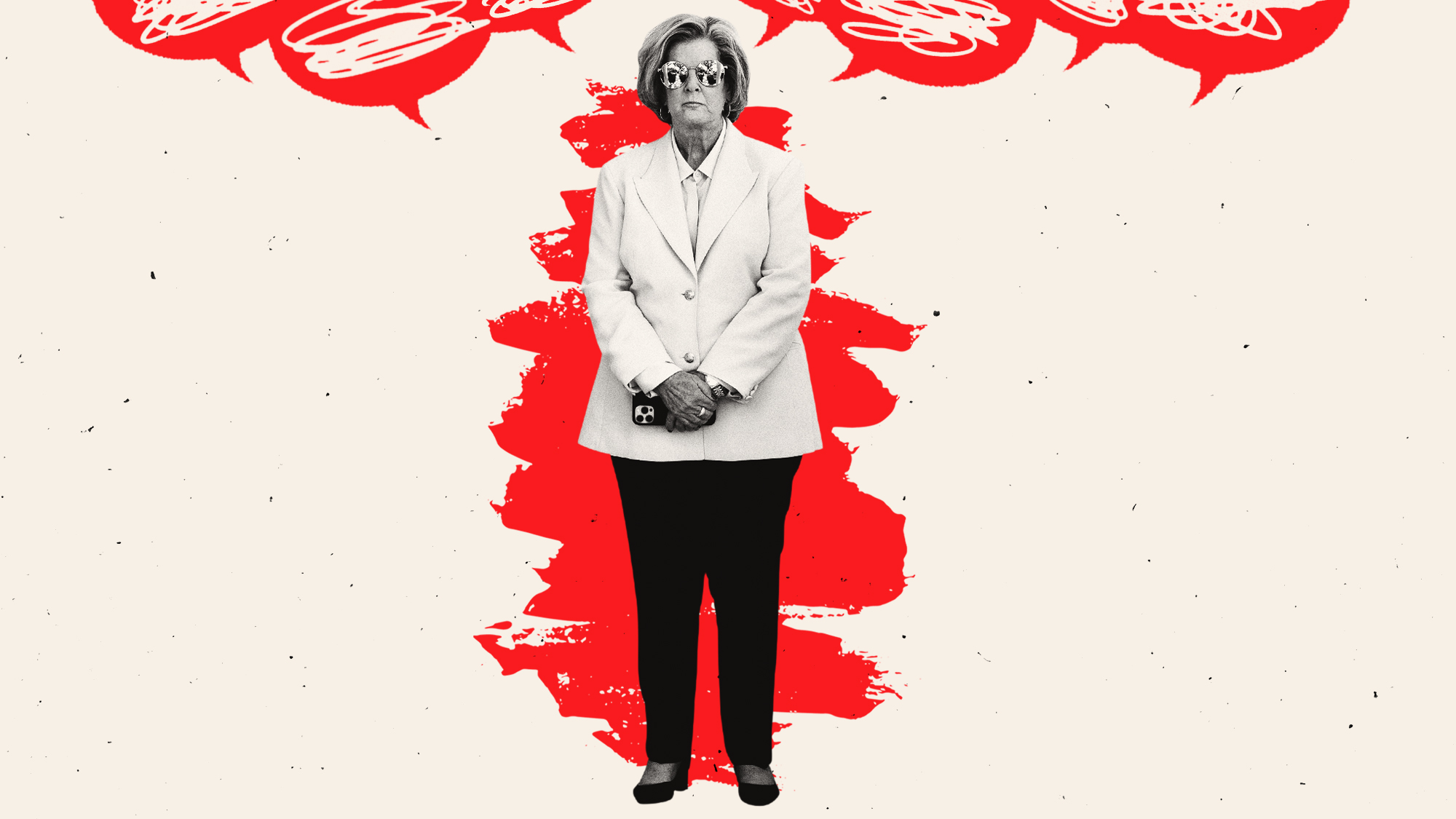

Tory MPs are in “open revolt” against Liz Truss and her plan for “growth, growth, growth”, according to reports.

Conservative politicians are “openly plotting how to put this government out of its misery”, an unnamed MP told the i news site, following a meeting between the prime minister and the 1922 Committee that backbenchers described as “painful”, “awful”, “funereal” and “brutal”, according to The Spectator.

Amid ongoing economic turmoil following Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget, many MPs and commentators are wondering whether Truss can deliver the economic growth that has been at the heart of her message. Others are questioning whether growth is the right goal for the country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the papers say?

Economic growth refers to an increase in a country’s gross domestic product, or GDP – the total value of goods and services produced over a specific period. It matters because “sustained rises in GDP have been shown, over the course of history, to improve our health, our wealth and our happiness”, said Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist.

In the post-war period there was a “good reason” to pursue growth, wrote Michael Jacobs in The Guardian, because it gave us “falling unemployment, rising incomes, lower inequality, higher tax revenues to pay for public services”, and “even some environmental improvement”.

However, said Jacobs, professor of political economy at the University of Sheffield, growth averaged around 2% a year from 2010 to 2019, “but disposable income has barely increased”. Why? Because the rise of “rentier capitalism”, in which ownership of land, property and company shares are “highly concentrated”, has meant the benefits of economic growth flow mainly to asset holders, “whose riches grow with no labour or effort on their part”. As a result, he believes “the obsession with GDP has to change”.

Matthias Schmelzer, at The New Statesman, also thinks Truss’s “focus on economic growth is politically misleading, economically wrong-headed and profoundly outdated”. The economic historian and social theorist believes her plan is “concealing a radical agenda of austerity” that will lead to fewer planning regulations and “lower social and ecological standards”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even if these policies were to achieve growth, it would be “a kind of economic expansion that curtails the prosperity of middle-income voters and further aggravates the ecological crisis”, he argued.

At the Financial Times, Tim Harford said that “a fashionable line of attack against Liz Truss’s single-minded focus on growth” is “what about the poor? What about the planet?” But he thinks this is “misguided”.

She is “absolutely right to believe that economic growth should be her top priority”, said Harford. “The problem is that she seems to have no idea how to go about it.”

He explained that it is “striking how countries with a high GDP also have flourishing citizens”.

“Pick your issue, from life expectancy to child mortality, from opportunities for women to the protection of basic human rights, cleaner streets, lower crime, even better-quality art, from TV to opera… somehow, people who live in richer countries are likely to be enjoying more of the good stuff.”

Michael R. Strain, director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, agreed that Truss is “absolutely right to focus on economic growth” because Britain is the only G7 country with a smaller economy today than in the fourth quarter of 2019, before the pandemic.

Writing for The Washington Post, Strain said that slow growth means “fewer opportunities for economic advancement”, “conflict over distribution”, as well as workers’ talents being “underutilised and energy untapped”. Ultimately, he wrote, slow growth means “dimmed aspirations and more modest dreams for the future”.

What next?

Truss and her chancellor hope to restore public, political and economic confidence in their plans. During the financial turmoil that followed his mini-budget on 23 September, Kwarteng said he would set out his economic plan and an independent forecast of the nation’s finances on 23 November.

Following an outcry from backbenchers and the markets, he said he would announce his plan on 31 October. This will “set out how he will fund tax cuts and reduce debt after his mini-budget sparked market turmoil”, said the BBC. An independent forecast of the UK’s economic prospects will be released at the same time.

Sky News today suggested that talks were under way in Downing Street “over whether to reverse parts of mini-budget”, but Truss’s aim for “growth, growth, growth” is unlikely to change.

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?Today's Big Question Trump has never conceded his loss that year

-

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?Today’s Big Question Centrists, lefty activists also debate abolishing ICE

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?Today’s Big Question Trump claims control over crude reserves, but challenges loom

-

What is China doing in Latin America?

What is China doing in Latin America?Today’s Big Question Beijing offers itself as an alternative to US dominance

-

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?Today's Big Question The president halts offshore wind farm construction

-

Why does Trump want to reclassify marijuana?

Why does Trump want to reclassify marijuana?Today's Big Question Nearly two-thirds of Americans want legalization

-

Why does White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles have MAGA in a panic?

Why does White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles have MAGA in a panic?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Trump’s all-powerful gatekeeper is at the center of a MAGA firestorm that could shift the trajectory of the administration