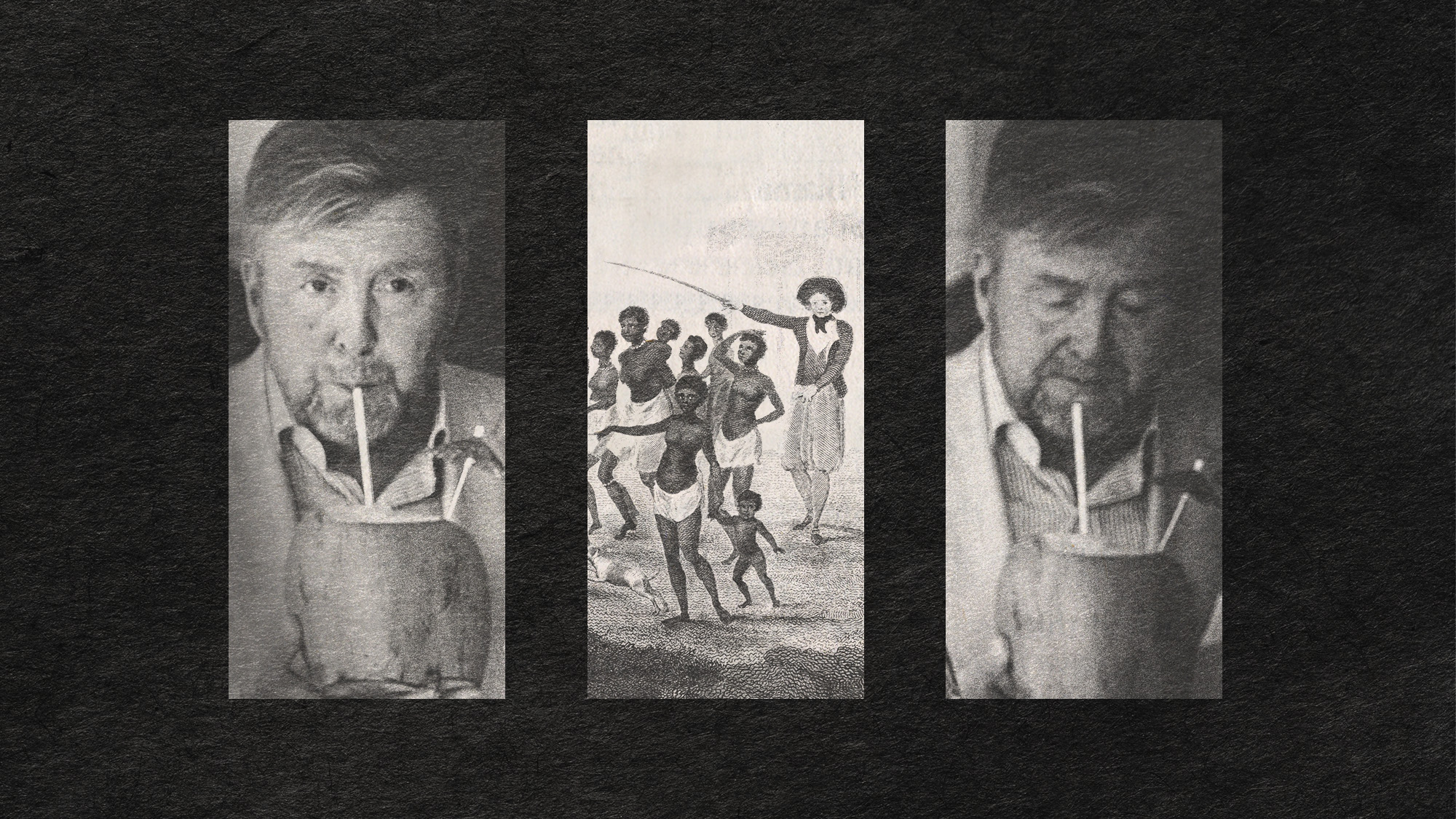

In Suriname, the spectre of Dutch slave trade lingers

Dutch royal family visit, the first to the South American former colony in nearly 50 years, spotlights role of the Netherlands in transatlantic trade

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Suriname celebrates 50 years of independence, the spectre of Dutch colonial rule and its role in the slave trade still lingers.

The king and queen of the Netherlands touched down in the small South American country last week: the first visit by the Dutch royal family in 47 years. King Willem-Alexander had vowed before the trip that the topic of slavery, which was formally abolished in Suriname and other Dutch-held territories in 1863, would not be off-limits. “We will not shy away from history, nor from its painful elements, such as slavery,” he said. Building a common future “is only meaningful if we take into account the foundation on which we stand”, he added. “That foundation is our shared past.”

But the shared past remained a source of tension in the present, as the king and queen prepared to meet representatives of slaves’ descendants.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Spoils of slavery

“The Dutch funded their ‘golden age’ of empire and culture in the 16th and 17th centuries by shipping about 600,000 Africans as part of the slave trade,” said The Guardian, “mostly to South America and the Caribbean.”

A study in 2023 found that the Dutch royal family had earned the current equivalent of £475 million between 1675 and 1770 from the colonies, “where slavery was widespread”. The ancestors of the current king were “among the biggest earners” from what the report described as the state’s “deliberate, structural and long-term involvement” in slavery.

Slavery was formally abolished in Suriname and other Dutch-held lands in 1863, and actually ended 10 years later after a “transition” period.

In 2022, then prime minister of the Netherlands Mark Rutte officially apologised for the Netherlands’ role in the transatlantic slave trade. The king followed with a royal apology the following year, echoing a similar address in 2003 when he acknowledged the devastation caused by slavery, and how his own family had benefited from what he called humanity’s greatest genocide.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Repercussions and reparations

During the visit, Willem-Alexander said the Netherlands was keen to deepen ties with its former colony “based on equality and mutual respect”.

Representatives of the descendants of African slaves and Indigenous people formally accepted the king’s apology. But the president of Suriname, Jennifer Geerling-Simons, has warned that the legacy of slavery lingers.

Willem-Alexander had previously offered $200 million (£149 million) to raise awareness about that legacy. Now, the king and his delegation are “being reminded” that the grant should not be considered part of a reparations package, said Caribbean Life.

“The losses they have suffered are significant,” said Geerling-Simons, referring to the descendants of slaves. “We’re not going to argue about that now, but this issue of reparations will have to be discussed someday.”

A reparations commission appointed by Caribbean governments deemed the Dutch “the most brutal and calculating of the European nations”, said the news site. The commission said the country had “invented the blueprint for the slave trade”.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Delcy Rodríguez: Maduro’s second in command now running Venezuela

Delcy Rodríguez: Maduro’s second in command now running VenezuelaIn the Spotlight Rodríguez has held positions of power throughout the country

-

Paradise sold? The small Caribbean island courting crypto billions

Paradise sold? The small Caribbean island courting crypto billionsUnder the Radar Crypto mogul Olivier Janssens plans to create a libertarian utopia on Nevis

-

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run out

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run outSpeed Read He will serve 27 years in prison

-

Rob Jetten: the centrist millennial set to be the Netherlands’ next prime minister

Rob Jetten: the centrist millennial set to be the Netherlands’ next prime ministerIn the Spotlight Jetten will also be the country’s first gay leader

-

Jamaicans reeling from Hurricane Melissa

Jamaicans reeling from Hurricane MelissaSpeed Read The Category 5 storm caused destruction across the country

-

What is Donald Trump planning in Latin America?

What is Donald Trump planning in Latin America?Today’s Big Question US ramps up feud with Colombia over drug trade, while deploying military in the Caribbean to attack ships and increase tensions with Venezuela

-

Dutch government falls over immigration policy

Dutch government falls over immigration policyspeed read The government collapsed after anti-immigration politician Geert Wilders quit the right-wing coalition