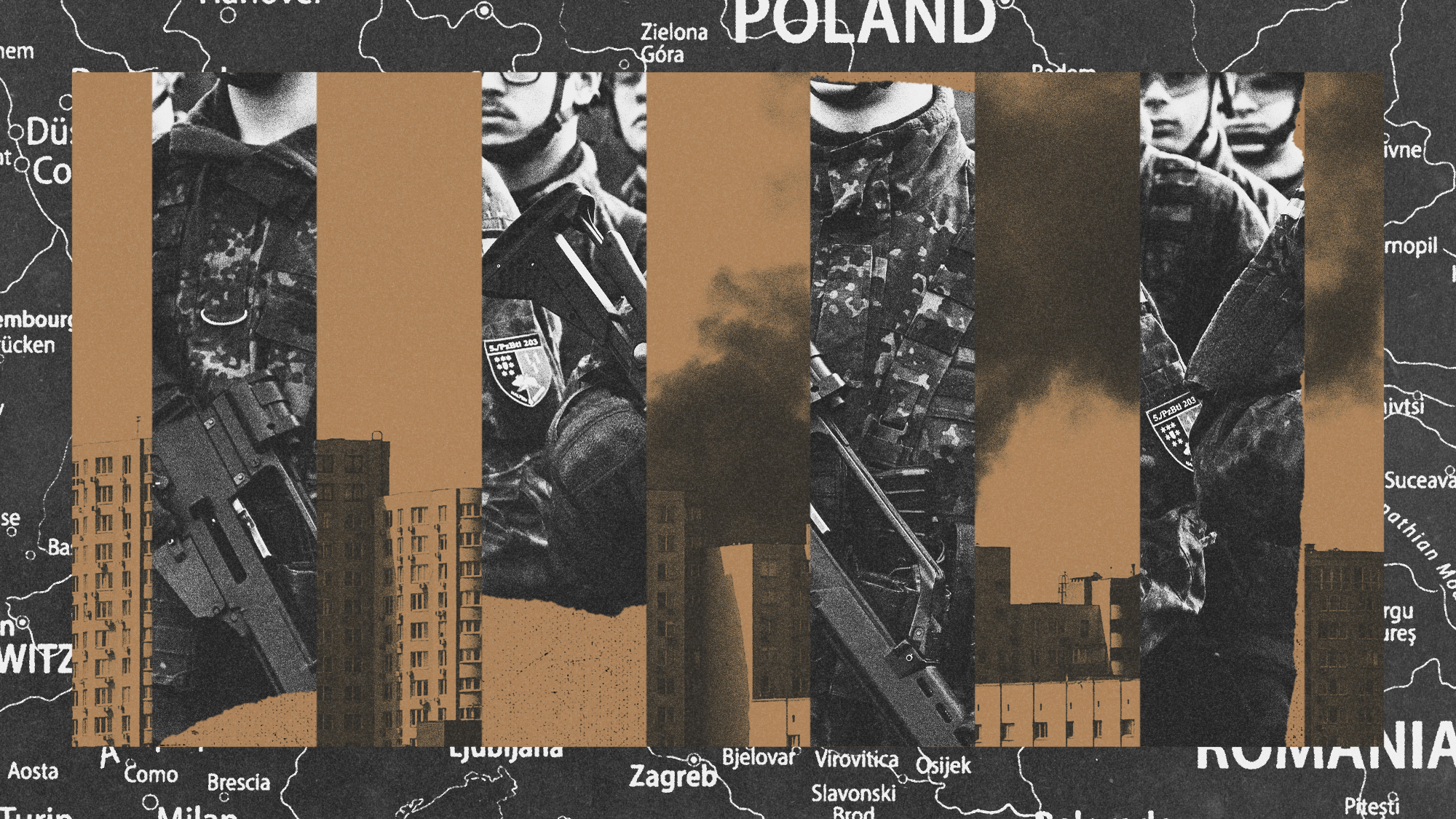

What will Russia look like after Putin?

There are no guarantees of stability for the West if or when the president departs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Analysts are forecasting that Vladimir Putin’s two-decade stint at Russia’s helm could be nearing its end after the attempted coup staged by the Wagner Group.

The president’s disastrous military defeats, his nuclear sabre-rattling and his endless raising of the stakes in Ukraine have forced even staunch pro-Kremlin commentators to question his decisions.

With rumours surrounding his health, his days in power might be numbered. But what would a post-Putin era mean for Russia and the world?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the papers say?

“It is tempting to believe,” wrote Calder Walton for Time, “that Russia would shake off its dictatorial shackles, normalise its relations with the West, and advance down the democratic road.” But, he warned, “such thinking is mistaken”.

The majority of Putin’s government are siloviki – “men of force… who have KGB or military backgrounds”, he added, and the president himself “is not necessarily the most hardline among them”.

So with “someone like Nikolai Patrushev, on Russia’s Security Council” or Putin’s defence minister Sergei Shoigu, or Alexander Bortnikov, an “old KGB hand and FSB director” in power, “the situation may be worse”, said Walton, because they “may have clearer heads than Putin”. Therefore, “the West may be better off with Putin than his alternatives”.

A “post-Putin Russia may look like Serbia after Milošević”, wrote Tony Barber for the Financial Times. Serbia after its strongman former president Slobodan Milošević “was no longer a warmongering, hyper-nationalist state” but “it evolved into a flawed democracy and remained at odds with the west”, Barber argued. Russia will “certainly not tailor its foreign policy to suit the west”, he predicted. “At home, the ruling group will ensure that nationwide elections always keep it in power.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There is “an ultranationalist tendency in Russian politics, once too unruly for Putin’s taste, but now with a louder voice because of the Ukraine war”, said Barber, and “it seems certain to play some role in setting the tone of future Russian politics”.

Over the last nine years, the “self-appointed tribunes of Russian nationalism” have been “boxed out of decision-making or co-opted for their symbolic value”, wrote Greg Afinogenov for London Review of Books. But “if they were ever to seize power for real, nothing good would come of it”.

One exit could be followed by another, according to an opponent of Putin. “Any post-Putin ruler would be significantly weaker in terms of legitimacy and public authority… the regime will try to hold on to power but will not last for long,” Vladimir Milov, a long-standing opposition politician who was deputy energy minister early in Putin’s rule, told The Guardian.

What next?

However, Putin is not about to step aside quietly, said some commentators, and the recent attempted coup may have actually strengthened his hand.

“The irony is that visions of a nuclear arsenal being divided between warlords and rival armies clashing on the European Union’s borders have helped Putin,” wrote Mark Galeotti in The Spectator, “discouraging some who would otherwise want to see a more assertive approach to the ageing autocrat.”

The president has “invoked the smuta”, the “‘Time of Troubles’ that followed the death of Ivan the Terrible”, added Galeotti, which was “characterised by dynastic crises, foreign invasion, hunger and revolt”. This evocation was “a clear attempt to push the ‘better the devil you know’ argument”, he added.

This argument has enjoyed some influence at home. “The army, the FSB and the technocrats who make things happen” are “thinking about life after Mr Putin”, said The Economist. “Yet even if they see him as a liability, they may not be prepared to act.”

They “fear repression” and see Putin “as a nail holding their dysfunctional system together”. It may be “rusty and bent”, but if they pull the nail out, “the whole lot will come tumbling down – and they along with it”.

The next presidential election is due in March 2024, by which time Putin will have been in power for a quarter of a century. Meanwhile, the world at large is considering what might come when he eventually leaves office. “The point is that the West cannot allow itself to be paralysed by a fear of what will follow Putin,” said Galeotti.

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expire

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expireThe Explainer The last agreement between Washington and Moscow expires within weeks

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

The history of US nuclear weapons on UK soil

The history of US nuclear weapons on UK soilThe Explainer Arrangement has led to protests and dangerous mishaps

-

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?Today's Big Question How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missile

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missileThe Explainer Russian president has boasted that there is no way to intercept the new weapon

-

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from Russia

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from RussiaUnder the Radar Reviving lost wetland on Nato’s eastern flank would fuse ‘two European priorities that increasingly compete for attention and funding: defence and climate’