Inside Venezuela’s oil corruption scandal

Private planes and luxury cars seized as £17bn allegedly goes missing from state-run company

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Dozens of business figures and politicians have been arrested so far this year in a £17bn corruption scandal that has rocked Venezuela and its state-run oil company.

Senior officials in President Nicolás Maduro’s government have been among those arrested in an ongoing crackdown that has had “government insiders scurrying for cover”, said The Associated Press.

It is “one of the biggest scandals to hit Venezuela in years”, said The Sunday Times. It has already led to the resignation of “the once seemingly untouchable” oil minister Tareck El Aissami and there are “fears that up to £16.7bn may have been stolen from the coffers of the nationalised oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The investigation, led by Tarek William Saab, Venezuela’s attorney-general, “has fed a splurge of lurid headlines, as the excesses of a corruption network fleecing a nation emerge”, the paper reported. Confiscated assets include 28 mansions, 19 aeroplanes, a hotel and 361 luxury cars, and there are allegations of a prostitution ring dubbed the Oil Dolls.

“They gave themselves a life that not even Gulf princes have,” the paper quotes Saab as saying.

The episode “offers a rare window into the chaos and corruption at the top of PDVSA”, said The Economist, “the state oil giant which Mr Maduro, following in the footsteps of his late predecessor, Hugo Chávez, has driven to near-ruin”.

The unfolding of a scandal

Oil has been “the backbone of Venezuela’s autocratic regimes for decades”, said The Economist. The country has one of the world’s largest oil reserves, and “successive presidents have been accused of stealing the easily tapped profits for their own use”, wrote The Sunday Times.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

PDVSA was once the second largest oil company in the world, during the oil boom in the early 2000s, when record high prices allowed the leftist Chávez to launch “numerous initiatives” for public services, reported Al Jazeera.

“But a subsequent drop in prices and government mismanagement”, first under Chávez’s government and then his successor, Maduro, “ended the lavish spending”, the site reported. “And so began a complex crisis that has pushed millions into poverty and driven more than seven million Venezuelans to migrate.”

In 2016, the then opposition-led National Assembly said $11bn had gone missing at PDVSA between 2004 and 2014.

El Aissami, who headed the Ministry of Internal Affairs under Chávez and served as vice-president from 2017 to 2018, was accused by the US in 2017 of participating in corruption, money laundering and drug trafficking: a “narcotics kingpin”, according to Al Jazeera. He denies all the accusations.

Two years later, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on PDVSA to try to pressure Maduro into resigning, after the Venezuelan president “blatantly rigged the previous year’s election”, said The Sunday Times. The company’s losses came about partly because it had become “more reckless” in order to evade the sanctions, The Economist said.

PDVSA became reliant on fellow sanctioned allies Russia and Iran to import and sell oil at a heavy discount. In 2019 Maduro ordered PDVSA to move its European office to Moscow. Venezuela began accepting payments in rubles or cryptocurrency.

‘Corruption and incompetence’

When the pandemic caused a global slump in demand for oil, production at PDVSA plummeted. In April 2020, El Aissami was appointed Venezuela’s minister of oil.

An audit of PDVSA’s accounts in March this year showed “corruption and incompetence on a monumental scale”, said The Sunday Times. The anti-corruption police issued a communique on 17 March, which led to the first round of arrests.

Saab told reporters the alleged scheme involved selling Venezuelan oil through the country’s cryptocurrency oversight agency, in parallel to PDVSA. Some cryptocurrency payments reportedly turned out to be either scams, or to lead to huge losses.

El Aissami stepped down on 20 March. He has not been mentioned as a target for the investigation, and has pledged to help investigators while also publicly declaring his support for Maduro’s anti-corruption campaign.

Stabilising the economy

Venezuela is considered one of the most corrupt countries in the world, ranked by Transparency International in 2022 as 177th out of 180 countries.

Officials “are rarely held accountable”, said Al Jazeera, “a major irritant to citizens, the majority of whom now live on $1.90 a day, the international benchmark of extreme poverty”.

“It would be very difficult for even a much less corrupt state to implement all the necessary controls,” Francisco Monaldi, who heads the Latin America energy programme at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, told The Associated Press.

Internal PDVSA documents showed that more than half of its fleet of 22 oil tankers are so run down that they are at risk of “sinking, fires, or spills”, Reuters reported, and should be immediately taken out of service or repaired.

Analysts suspect Maduro may be seeking to stabilise the economy before next year’s presidential elections. The local currency, the bolívar, has slumped sharply against the dollar.

The anti-corruption drive, said OilPrice.com, could also be an attempt to persuade the US to lift sanctions on Venezuela.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The spiralling global rice crisis

The spiralling global rice crisisfeature India’s decision to ban exports is starting to have a domino effect around the world

-

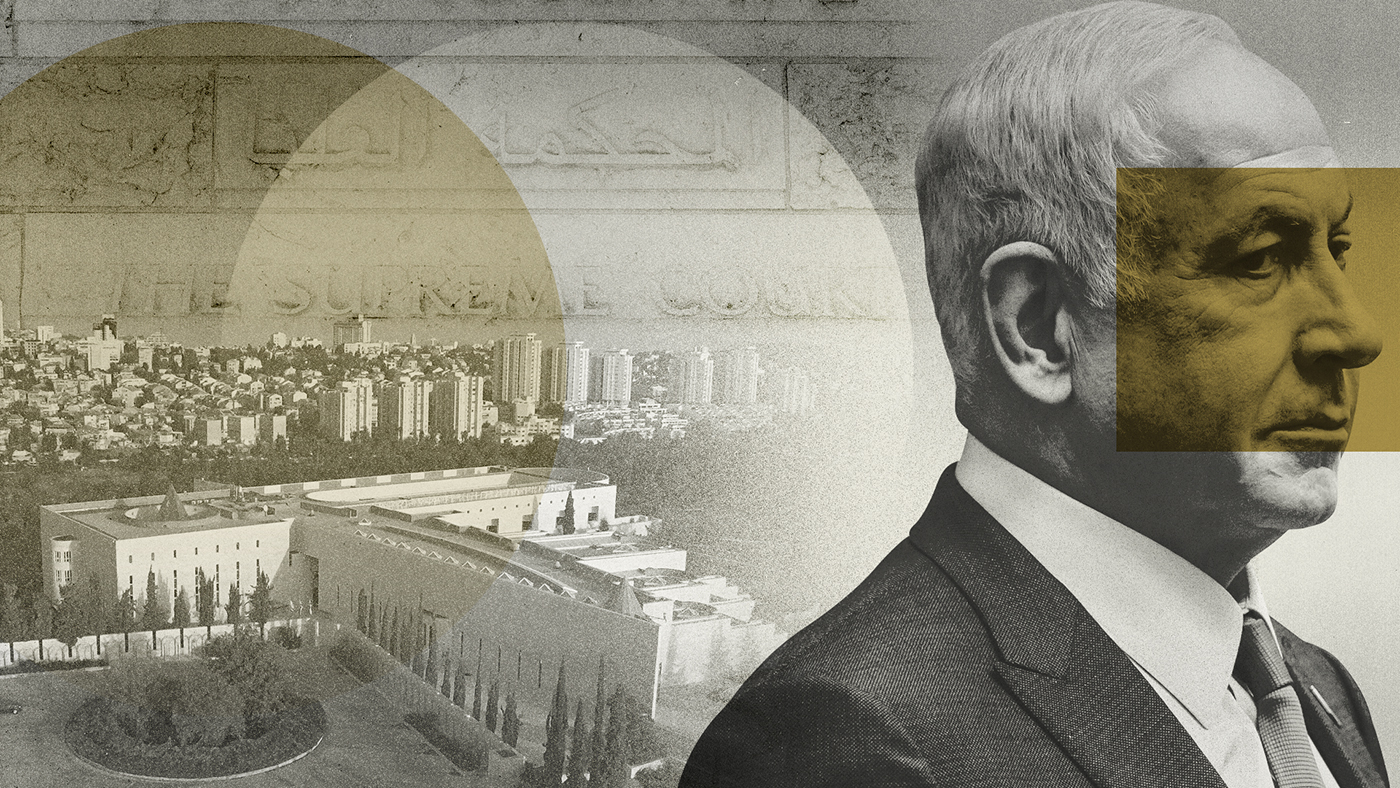

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

A country still in crisis: Lebanon three years on from Beirut blast

A country still in crisis: Lebanon three years on from Beirut blastfeature Political, economic and criminal dramas are causing a damaging stalemate in the Middle East nation

-

Ghana abolishes the death penalty

Ghana abolishes the death penaltyfeature It joins a growing list of African countries which are turning away from capital punishment

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders

-

The sinister side to India’s fantasy gaming craze

The sinister side to India’s fantasy gaming crazefeature Fantasy gaming is booming in India, despite the country's ban on gambling

-

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classes

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classesfeature Reports of the death of the Chinese economy may be greatly exaggerated say analysts

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some