Illicit mercury is poisoning the Amazon

'Essential' to illegal gold mining, toxic mercury is being trafficked across Latin America, 'fuelling violence' and 'environmental devastation'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the deadliest chemicals on Earth is being smuggled across Latin America – and is poisoning the environment along the way.

Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin and its use is banned or heavily restricted throughout the world. But it's "essential" to illegal gold mining, one of the Amazon's "most destructive criminal economies", said The Associated Press,

Once extracted from the Earth's crust, mercury "persists in the environment indefinitely", said The Guardian. Those who drink water and consume food contaminated by it are gradually poisoned. But, with the current record-high gold prices, the mercury trade has become "so lucrative that one of Mexico's deadliest cartels has entered the business".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 'gold-mercury-drug trifecta'

Last month, Peruvian authorities seized about four tonnes of mercury hidden inside gravel sacks in a Mexican container on a cargo ship bound for Bolivia. It was the largest mercury seizure made in South America. Mercury mining in Mexico is "spinning out of control", according to a recent report by the non-profit Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA). More than 180 tonnes were trafficked from Mexico to Colombia, Bolivia and Peru between April 2019 and June 2025, as part of what the Washington-based organisation calls a "gold-mercury-drug trifecta".

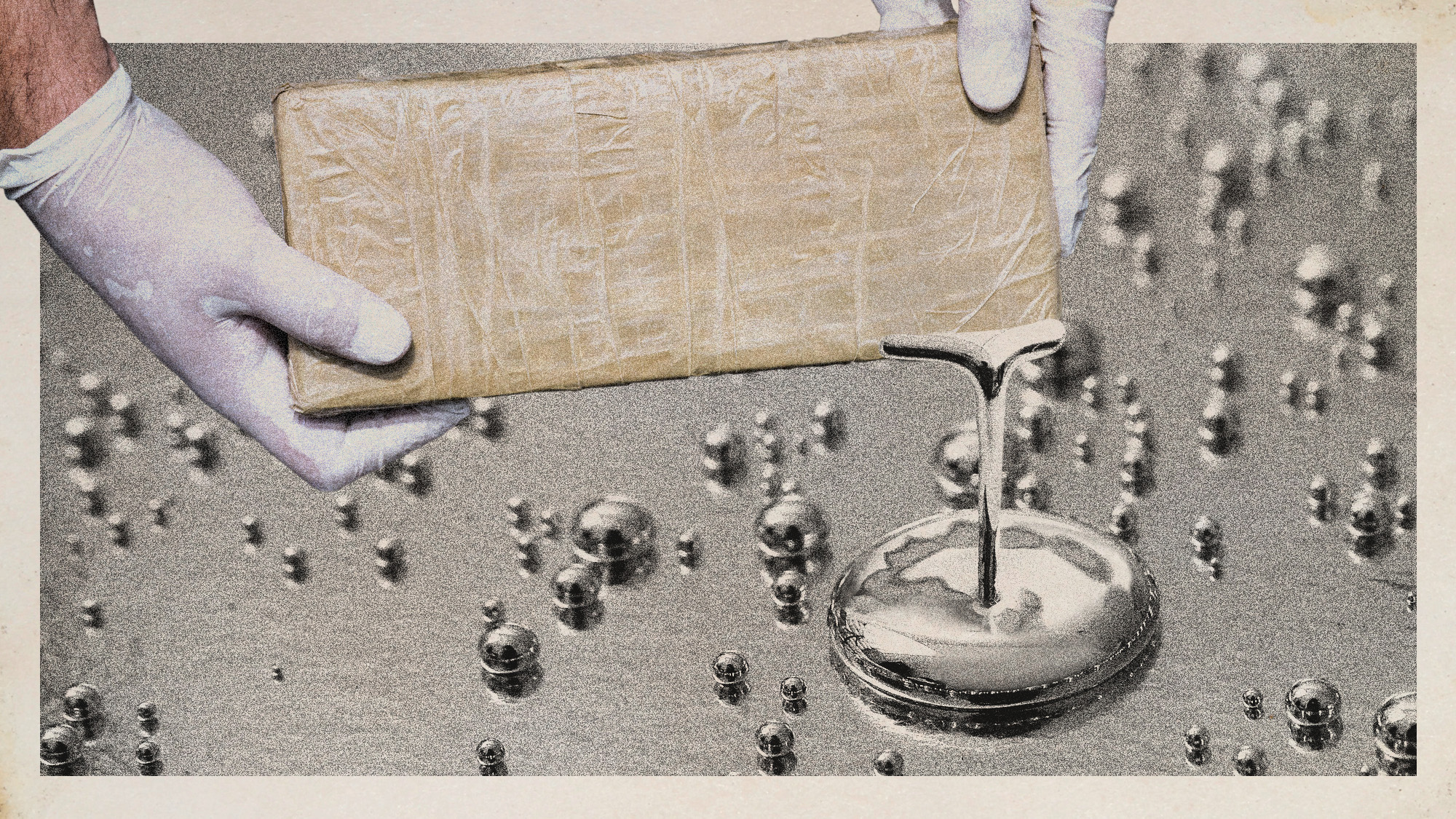

Miners mix mercury with sediment and heat it until it vaporises, leaving the pure gold ore – and releasing toxic vapour into the air, water and soil. Leftover mercury washes into rivers, where it transforms into methylmercury: its most dangerous form. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining releases 800 tonnes of mercury into the rainforest every year.

In 2013, 128 countries signed up to the Minamata Convention and committed to restrict the production and export of mercury, before phasing it out by 2032. But "legal loopholes" in the UN-based treaty "benefit traffickers and illegal gold miners", said the EIA, warning that the trade is "fuelling violence, forest destruction", human rights abuses and "environmental devastation".

In Latin America, governments and law enforcement agencies have struggled to stem the flow. Peru and Brazil banned mercury imports in 2016 but, "in Bolivia, it is easier to import mercury than to import books or medicines", said Oscar Campanini, director of the non-profit Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

'Profound impact'

The surge in mercury trafficking has been driven by soaring gold prices. According to World Gold Council estimates, 30% of gold mined around the world comes from "untraceable" sources – a $12 billion (£9 million) black market that has "created a toxic web of environmental degradation and public health risks", said AI Invest.

It's having a "particularly profound impact" on the health of Indigenous people, said Mongabay, a non-profit environmental media organisation. Communities that live near mining sites in the Amazon have been exposed to high concentrations of mercury. In Peru's Madre de Dios region, an "epicentre of illegal mining", mercury contamination has been detected in drinking water and even breast milk, said AP. Long-term exposure can cause "irreversible damage to the brain and nervous system, particularly in children and pregnant women".

There are equipment and methods that can replace mercury in the gold mining process, and reduce the risk of contamination – but there is currently little market incentive to adopt them.

The issue is "expected to take centre stage" at the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention in November, where advocates "hope to eliminate legal loopholes" and enforce phase-out timelines. Authorities say last month's bust "marks a turning point in efforts to dismantle the supply chains".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Mexico’s forced disappearances

Mexico’s forced disappearancesUnder the Radar 130,000 people missing as 20-year war on drugs leaves ‘the country’s landscape ever more blood-soaked’

-

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'The Explainer Brazil's former president will likely be found guilty of attempting military coup, despite US pressure and Trump allegiance

-

Thailand is rolling back on its legal cannabis empire

Thailand is rolling back on its legal cannabis empireUnder the Radar Government restricts cannabis use to medical purposes only and threatens to re-criminalise altogether, sparking fears for the $1 billion industry

-

Narco subs are helping to fuel a global cocaine surge

Narco subs are helping to fuel a global cocaine surgeThe Explainer Drug smugglers are increasingly relying on underwater travel to hide from law enforcement

-

North Korea may have just pulled off the world's biggest heist

North Korea may have just pulled off the world's biggest heistUnder the Radar Hermit kingdom increasingly targets vulnerable cryptocurrency, using cybercrime to boost battered economy and fund weapons programmes

-

Mexico extradites 29 cartel figures amid US tariff threat

Mexico extradites 29 cartel figures amid US tariff threatSpeed Read The extradited suspects include Rafael Caro Quintero, long sought after killing a US narcotics agent

-

Haitian gangs massacre hundreds accused of 'witchcraft'

Haitian gangs massacre hundreds accused of 'witchcraft'Under the Radar Vodou practices blamed for gang leader's son's illness, as elderly are hacked to death in Port au Prince

-

Italy's prisons crisis

Italy's prisons crisisUnder the Radar Severe overcrowding, dire conditions and appalling violence have brought the Italian carceral system to boiling point