Haitian gangs massacre hundreds accused of 'witchcraft'

Vodou practices blamed for gang leader's son's illness, as elderly are hacked to death in Port au Prince

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Haiti's gangs have crossed a "red line", after allegedly killing at least 184 people they suspected of witchcraft.

Gang leader Micanor Altès is said to have ordered the knife-and-machete "massacre" in the capital Port-au-Prince last week because he suspected people of practising witchcraft to make his child ill. At least 127 of the victims were elderly, according to Haiti's National Human Rights Defense Network (RNDDH), said CNN.

Altès – also known as Monel Felix, Alfred Mones, "Mikanò" and "King Micanor" – took "advice from a voodoo priest", who "accused elderly people in the area" of using witchcraft to harm his child, an RNDDH report said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The transitional government of the violence-ridden Caribbean nation has vowed to bring the perpetrators to justice. "A red line has been crossed, and the State will mobilise all its forces to track down and annihilate these criminals," said a statement from the Haitian prime minister's office.

'100% voodoo'

Voodoo, or Vodou as it's known in Haiti, is one of the country's official religions, along with Christianity. It is widely practised in all parts of society. A "common local joke", according to the Los Angeles Times, is that Haiti is "70% Catholic, 30% Protestant, and 100% voodoo".

Vodou is thought to have its roots in "tribal religions" that were brought to Haiti, then known as the French colony of Saint-Domingue, by West Africans taken as slaves, said Al Jazeera.

Practitioners believe that all living things – including animals and plants – have spirits, and use rituals, prayers and dances to connect with them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But Vodou has long been "attacked by other religions", and negative stereotypes about Vodou, in "racially coded language", have been used to "pathologise Haitian culture".

Just this year, Donald Trump accused Haitian immigrants in Ohio of eating pet dogs and cats, and "disinformation flooded the internet". Elon Musk, Trump's most prominent backer, shared a video, on his social-media platform X, showing a woman of apparently Haitian origin describing animal sacrifice as common Vodou practice – a claim that has been widely debunked.

Vodou has also been the focus of Haitian gang violence before. Altès is believed to have ordered the killing of 12 elderly female Vodou practitioners in 2021.

'Spiral into the abyss'

Haiti has been "convulsed by violence" since earlier this year, when gangs banded together in a coalition known as Viv Ansanm (Living Together) to "attack government institutions", including prisons and hospitals, said The New York Times.

In the spring, the gangs succeeded in "forcing out a prime minister", and they now control about 85% of the capital and vast swathes of the countryside – despite the presence of a UN-backed police force. Overall, about 5,000 people have been killed by gang violence this year, and more than 700,000 displaced, according to the UN. More than half of those displaced are children.

Attempts by gangs to gain new territory have led to "particularly bloody incidents in the past two months", said the BBC. Ordinary residents, rather than rival gang members, are increasingly being targeted.

The brutality of these latest killings reflects the country's "accelerating spiral into the abyss", William O'Neill, the UN's human-rights expert for Haiti, told the New York Times.

The "slaughter" centred on a "sprawling slum" in the Cité Soleil area – in one of the most "impenetrable gang strongholds", known as Wharf Jérémie. "Mutilated bodies were burned in the streets," said the RNDDH report, and then flung into the sea.

It is now "a ghostly place," said El País. "Its narrow streets, once full of life, remain desolate", and "the few residents who dare to go out do so with their eyes fixed on the ground". The bodies of some massacre victims remain "covered by white sheets", a testimony to "the scale of the horror."

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probe

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probeSpeed Read Shawn DeRemer, the husband of Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, has been accused of sexual assault

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein ties

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein tiesSpeed Read The younger brother of King Charles III has not yet been charged

-

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murder

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murderSpeed Read Sean Grayson was sentenced for the 2024 killing of Sonya Massey

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'

The trial of Jair Bolsonaro, the 'Trump of the tropics'The Explainer Brazil's former president will likely be found guilty of attempting military coup, despite US pressure and Trump allegiance

-

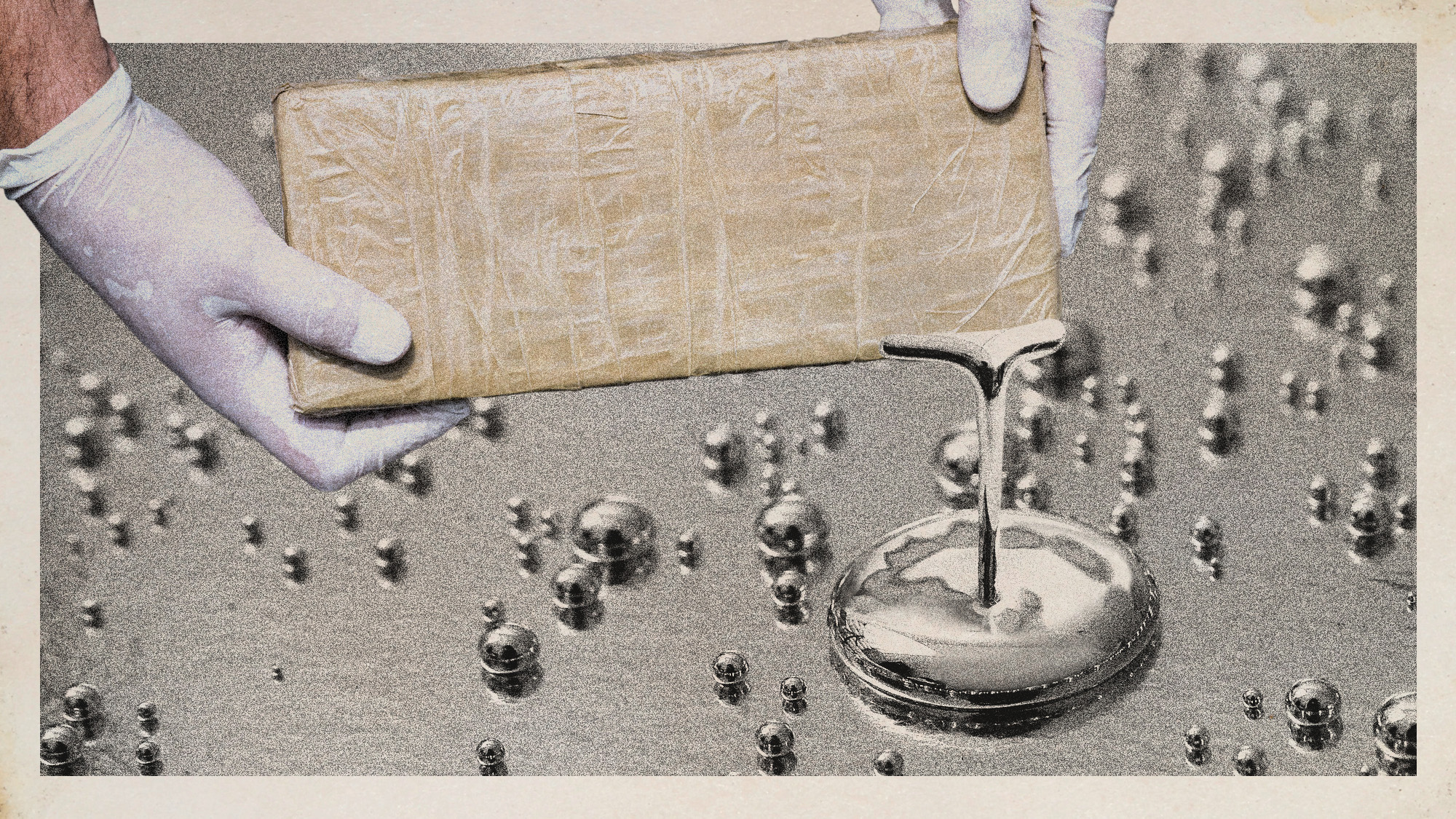

Illicit mercury is poisoning the Amazon

Illicit mercury is poisoning the AmazonUnder the Radar 'Essential' to illegal gold mining, toxic mercury is being trafficked across Latin America, 'fuelling violence' and 'environmental devastation'

-

Thailand is rolling back on its legal cannabis empire

Thailand is rolling back on its legal cannabis empireUnder the Radar Government restricts cannabis use to medical purposes only and threatens to re-criminalise altogether, sparking fears for the $1 billion industry

-

Australian woman found guilty of mushroom murders

Australian woman found guilty of mushroom murdersspeed read Erin Patterson murdered three of her ex-husband's relatives by serving them toxic death cap mushrooms

-

Crime: Why murder rates are plummeting

Crime: Why murder rates are plummetingFeature Despite public fears, murder rates have dropped nationwide for the third year in a row