Why China dominated Biden's Europe trip

What does something called the Atlantic Alliance have to do with a rivalry across the Pacific?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In his first visit to Europe since his inauguration, President Biden declared that "America is back," and that our commitment to collective security through the NATO alliance is "sacred." The United States would absolutely honor its obligations under Article V, and would strengthen trans-Atlantic ties that, he claimed, are fundamental to American and European security, going so far as to say that if NATO didn't exist, we'd have to invent it.

But Biden brought another message to Europe: that the most important threat to world order (and to America's place in that order) isn't in Europe at all. It's China. And Biden's team made it clear that their key objective at the NATO summit and subsequently in Brussels would be to bring America's European allies into a common front against the People's Republic.

They achieved some success in that effort. But the question lingers: What on Earth does something called the Atlantic Alliance have to do with a rivalry across the Pacific?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From its formation until the end of the Cold War, the purpose of the NATO alliance was to deter a Soviet attack on western Europe, and by assuring European capitals of their security, to prevent their Finlandization as well. Its implicit purpose was also to sustain western unity against the revival of those forces that had torn the continent apart in two world wars. Lord Ismay, NATO's first secretary general, put it pungently when he said that NATO's purpose was to "keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down."

The first of these purposes has been obsolete for 30 years. Since the end of the Cold War, then, the second and third purposes have predominated, but in a mutated form. Europeans have sought to keep America invested in their defense, and thereby keep their own defense expenditures lower, while America has sought to prevent European countries from pursuing a truly independent defense capability, and thereby transform NATO from a defensive alliance into a force multiplier for American power.

That's the NATO that went to war in Afghanistan — with America's allies fulfilling their Article V obligations in a theater that none of them ever expected to fight in. It's also the NATO that launched a war in Libya, an Anglo-French project that America "led from behind" (as President Obama put it) in part because our allies no longer had the capability to conduct the operation without us. And that's the NATO that Biden is looking to enlist against China.

It's not at all clear though why Europe's nations would want to be enlisted in this way. China poses no direct military threat to our European allies. Yes, China is building bases in Africa, is cooperating with Russia, is active in cyber warfare, and is building anti-satellite capabilities, all of which should be of concern in European capitals. But if China has a single grand strategic objective, it is to eject the United States from its position in the western Pacific and become the overwhelmingly dominant power there. That's an ambition that could bring China into direct conflict with the United States, and quite possibly to war. Why would our European allies want to risk being drawn into such a conflagration?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One answer is supposed to be something about the rules-based international order. But NATO flouts that order more readily than it upholds it, launching wars against Serbia and Libya without any legal justification that a neutral observer could accept. Another answer is something about democracy, and the threat the PRC poses to it. But the proximate threats China poses to freedom lie mainly in the way it leverages its economic clout and its technological capabilities, not in the military sphere. It makes all the sense in the world for the United Stats to play hardball with Europe to form a common front against Huawei in 5G. But in that negotiation we should be leveraging our own economic clout. What does that have to do with NATO, which is supposed to be a defensive military alliance?

Reading between the lines, Biden brought a much tougher message to Europe than what the happy talk about sacred obligations suggests. Implicitly, the message was that America gauges the value of that sacred alliance in terms of European willingness to form a common front against China, and to subordinate their interests to American interests in that contest. If Europe will do that, then America will happily continue to shoulder the lion's share of the burden of European defense. If not, then American priorities will inevitably shift — and shift away from Europe.

That's not so different from the message that Trump and his diplomatic team brought in their undiplomatic way, nor from the message of Obama's "pivot to Asia," which was as much a pivot away from Europe as from the Middle East. It's being phrased far more warmly and hopefully, which is always appreciated, and in a new context where Europe is more alive than ever to the largely non-military threats that China does pose to its independence. But in the end it presents European governments with the same ultimatum.

Since ultimata are not a good basis for a relationship, it would be wise for both sides to take a step back and reconsider whether NATO still has a purpose, and if so, what it is. America no longer has an interest in keeping the Germans (or the rest of Europe) "down" if it means taking primary responsibility for policing the Balkans or deterring Russian interference in their near-abroad. We would be better served by a more capable Europe even at the price of greater European independence. Europe, meanwhile, no longer has an interest in keeping the Americans "in" if it means getting roped into unrelated conflicts created by America's hegemonic position. Europe would be better served by the ability to choose when to stand shoulder to shoulder with us, and when to put a little distance.

As for confronting China, America's natural partners on the geopolitical side are the other members of the Quad, which will likely prove most effective to the degree that it does not mimic NATO's structure but retains each party's independent freedom of action. Europe's natural role would be to play the honest broker keeping the Sino-American rivalry from escalating to war, and working to restore the tattered rules-based international order that America has poked so many holes in over the past few decades, and that China would happily see tossed aside entirely.

We should vigorously pursue our own interests while also welcoming any positive contribution our European allies can make to preserving peace and freedom. But we shouldn't expect them to see our interests as perfectly aligned, or demand they speak as if they are when they are not. If we really are joined by sacred bonds, then they shouldn't feel like handcuffs.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

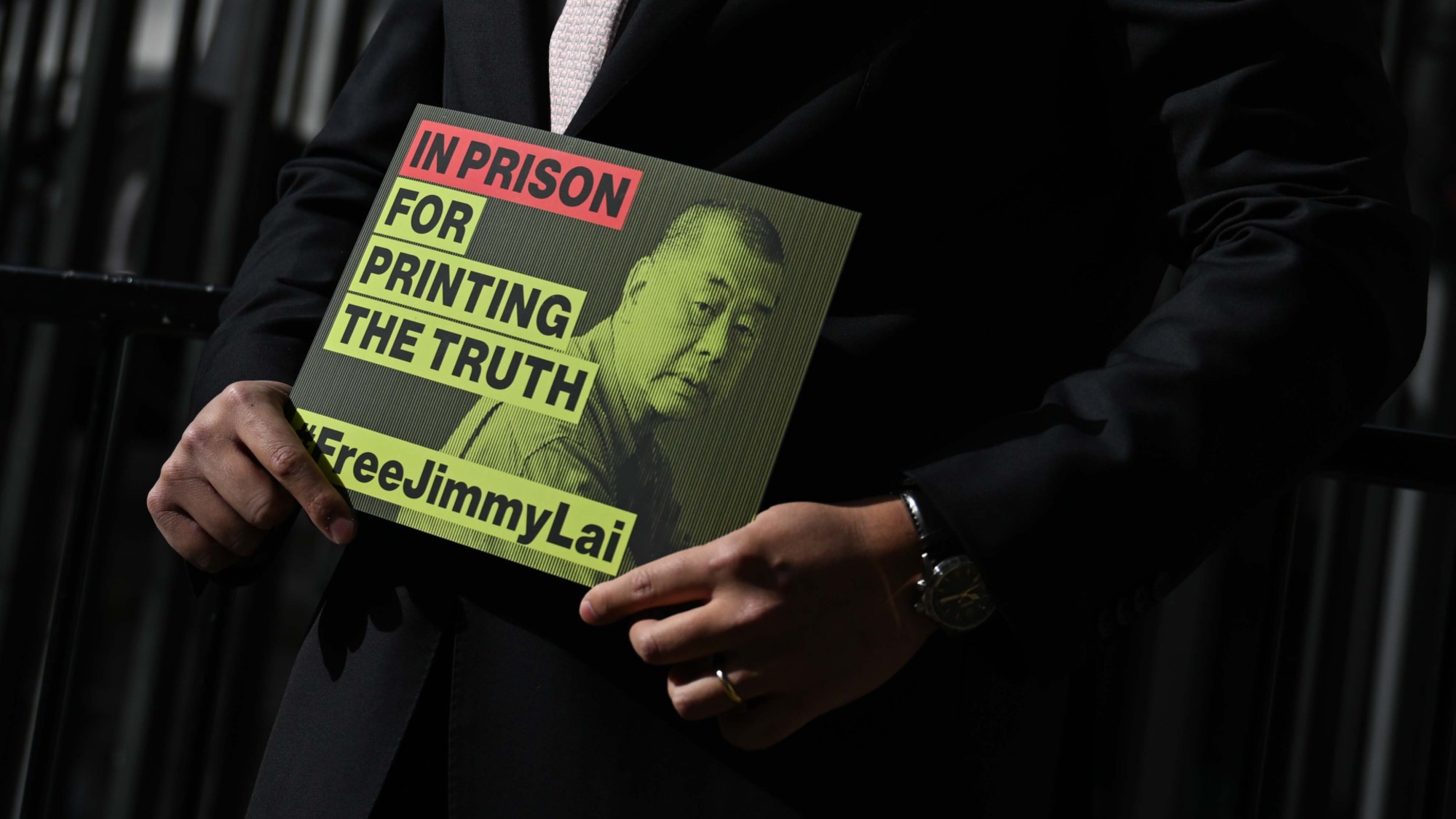

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?Today’s Big Question Analysts say China’s leader is still focused on reunification

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

What is China doing in Latin America?

What is China doing in Latin America?Today’s Big Question Beijing offers itself as an alternative to US dominance

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story