The disappointing uselessness of expertise

When everyone is an expert, whose word carries weight?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Expertise has won. All hail expertise. But also, all ask: What is expertise doing to American politics?

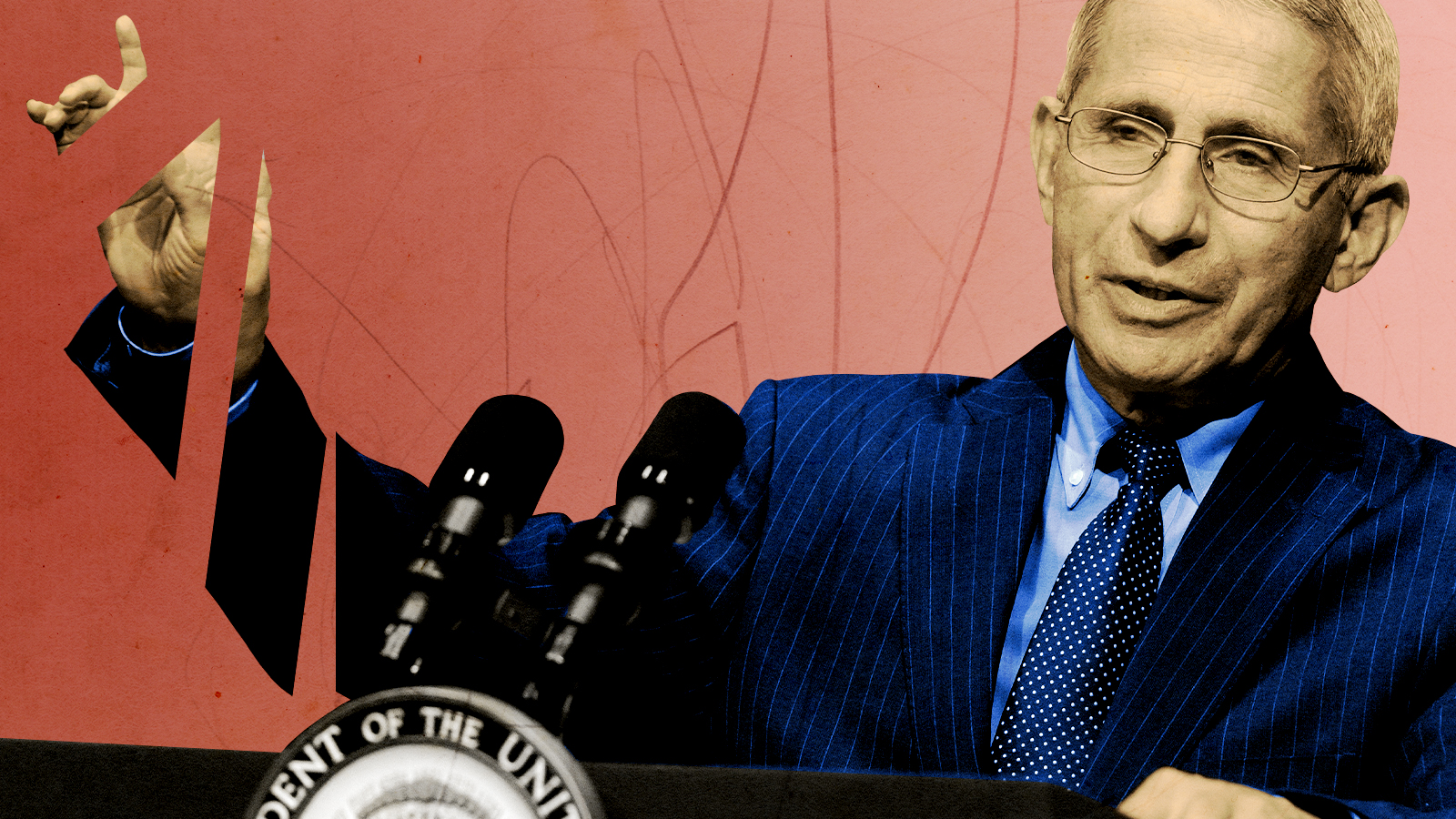

The old tendency to say intellectuals have allowed their book learning to confuse them, that what we need is good old common sense, is more or less dead. Even throughout the coronavirus pandemic, where the prominence of experts might have occasioned their challenge, the public has rarely turned against expertise itself. Opponents of the expert consensus on COVID have not aimed at discrediting epidemiology tout court; they've pointed to different experts who diverge from that consensus and suggested we listen to them instead. In this imagination, chief of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and White House medical adviser Anthony Fauci isn't incompetent, myopic, or ignorant so much as corrupt, knowingly making public health policy to benefit himself. A charge of malicious expertise, ironically, still recognizes and values expertise.

And it's not just the pandemic. For any point of view on any issue of concern in American politics, somewhere think tank staff are hard at work proving the case. No matter who you are or what you think, you can get expert imprimatur for your beliefs. Someone with credentials will dub your ideas legitimate. It's not for nothing that economists John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek are still frequently mentioned decades after their most influential works were published, often without any significant connection to those works. Their names alone are a kind of totem, powerful enough to bestow broadly recognized intellectual authority and give whatever you say next the sheen of expertise.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, having more experts on your side than your opponent does won't settle any dispute, because the American popular conception of expertise is convoluted at best. It's good when the experts agree, but it's also good when one expert declares all the other experts wrong. (Think about how we portray Galileo going before the Inquisition, or, in recent years, the online fascination with the conflict between inventors Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla.) Having many experts on your side can help you win an argument, but so can having an embattled, noble few. Either you're agreed with our society's most learnèd members, or you're standing with bold truth-tellers against an archaic establishment. Can't lose either way.

This may be the death of expertise, as Tom Nichols suggested in The Death of Expertise. But that's only half the picture. It is certainly the death of experts if there's no functional difference between someone widely recognized in their field for their accomplishments and experience and a guy with a YouTube channel. But the idea of expertise has triumphed so thoroughly that our guy with a YouTube channel doesn't dismiss the concept of expertise. He claims to be an expert too. The reason he says "I do my own research" instead of asserting that he instinctively knows the answers is because research is what experts do. It's a large part of what makes them experts.

Sure, it's a lot like a barbarian general pretending that what he rules over is "the Roman Empire," in a sense, since his kingdom still uses the Roman administrative system, and he pretends to be the subject of the emperor in Constantinople. The idea is so powerful and so prestigious that everyone wants to be associated with it, even if it means hollowing out what it originally meant until it hardly describes anything at all. The same thing has happened to expertise: Everyone loves it and claims it; no one agrees on what it is.

Explaining how we got to this point is beyond my scope here. I could gesture at specialization and bureaucratization in government, business, and academia alike; increased access to higher education; and how easy it is, in the internet age, to find experts who endorse all your preconcieved ideas. But perhaps the more important exercise is to ask: What does this mean for our politics?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On the one hand, not much at all. Invoking expertise is just a new tactic in longstanding debates, and the triumph of expertise won't cause a realignment.

On the other hand, quite a lot. Alabama Gov. George Wallace (R) could refer to "pointy-heads who couldn't ride a bicycle straight" and, for his audience, effectively skewer a distant, progressive elite. But expertise is politicized differently now. The question is no longer, "Are the experts worth following?" but, "Which experts should we follow?"

This is why slogans like "trust the experts" and "follow the science," so common in the past couple years, are basically meaningless and only persuasive in in-group contexts. Everyone knows what these actually mean, and it's not "the American Enterprise Institute is correct on all matters of public policy." Liberals might feel good imagining their opponents simply refuse to listen to anyone with letters after their name, but that's no longer an accurate picture, if it ever was. Now, everyone on all sides says they're following the science. Everyone on all sides says they're listening to the experts. But whose science? Which experts?

Appealing to expertise won't let us escape from polarization to some higher plane where issues can be discussed reasonably and rationally. That plane doesn't exist, and expert appeals could no longer get you there even if it did.

We've all decided expertise is good, but instead of refining our debates, that has made claims of expertise an abstraction, useless for solving any concrete problem. We're still stuck in the muddle of politics, because agreeing we should let the experts run things doesn't decide which experts, or how much running they should do, or in what way. "What do the experts say?" has become just another question for debate.

Is there some escape? I don't know. Don't look at me. I'm not an expert.

Steve Larkin is a writer from the state of Maine. His writing has appeared in The Week, the Catholic Herald, and other publications.

-

Political cartoons for February 14

Political cartoons for February 14Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include a Valentine's grift, Hillary on the hook, and more

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred