Why does the US media often neglect missing people of color?

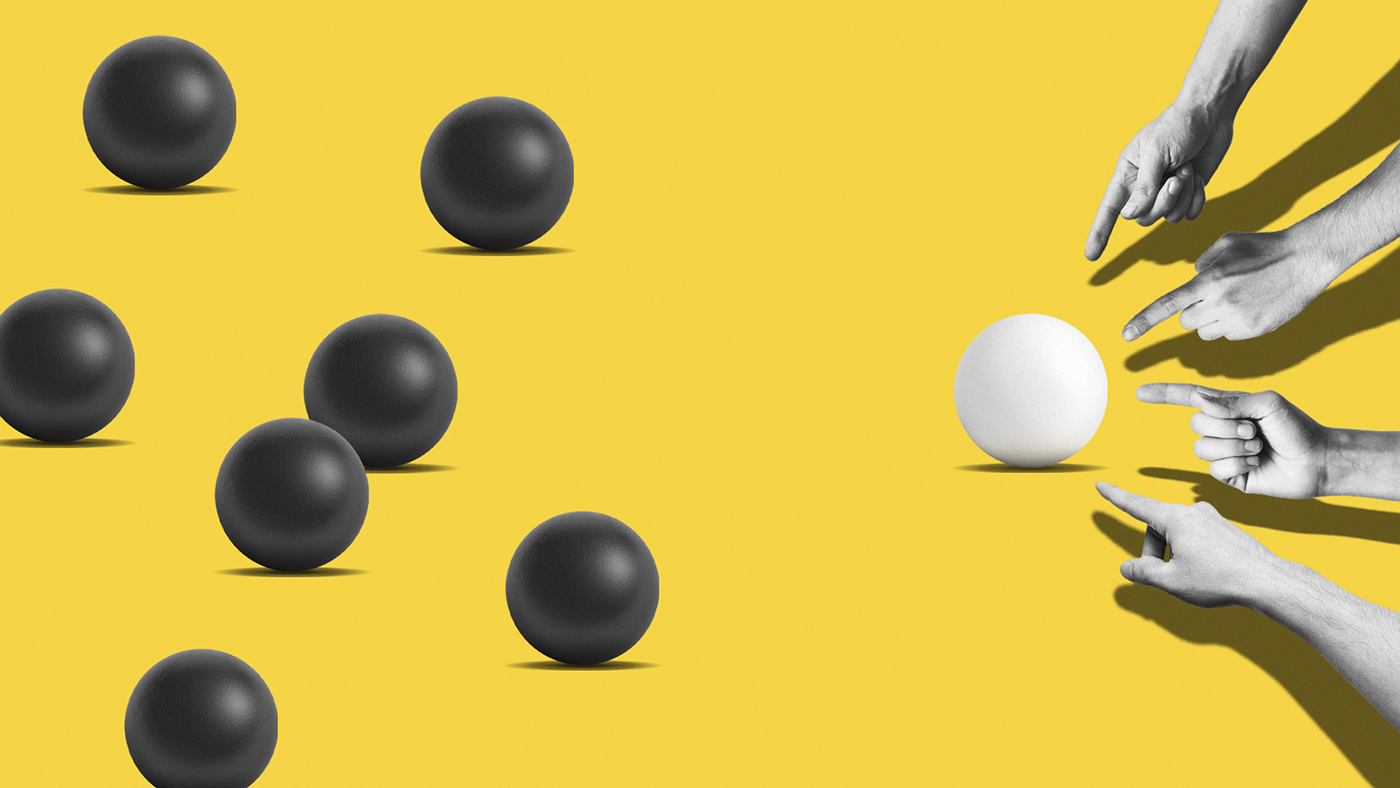

The balance of coverage between missing white Americans and missing Americans of color appears tragically skewed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Joran van der Sloot, the suspect in Natalee Holloway's death, will be extradited to the United States on charges related to her disappearance. His extradition comes nearly 18 years after Holloway vanished on the island of Aruba and more than a decade after she was declared legally dead.

Though years have passed, the media fervor surrounding Holloway's disappearance has never truly stopped, and her case has been adapted into numerous true crime series and made-for-TV films. For some, the incessant coverage of Holloway is a prime example of "Missing White Woman Syndrome," a term coined by the late journalist Gwen Ifill, who said, "If there's a missing white woman you're going to cover that, every day." (Additional research has shown "Missing White Woman Syndrome" can also apply to men and especially children.)

The coverage of Holloway's disappearance has been compared to that of LaToyia Figueroa, a Black woman who vanished less than a month after Holloway; she was later found murdered. Figueroa's disappearance received almost no coverage on cable networks, despite the similarities between her case and Holloway's. Many minority communities subsequently began to believe "national news outlets focus relentlessly on missing white women, while giving little attention to equally compelling stories involving poorer minority women," The New York Times reported. Case in point: The FBI's 2020 missing persons report showed that its case files disproportionately covered white people over people of color.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What are commentators saying?

"Missing White Woman Syndrome" syndrome is partially due to a legacy of racism in the U.S., and "for missing Black people, police and mainstream outlets do very little, if anything, to recover them," Derecka Purnell reported for The Guardian. The police and the media "have a longer history of hurting than of helping" missing minorities. This has perpetuated "the notion that the amount of media coverage that a missing person receives, or the number of resources that police expend to find them, is a litmus test for the value of Black life ... why do we give the media and the police so much power to decide how human we are?"

Many of these coverage decisions are also happening in newsrooms "that continue to be disproportionately white," Martin G. Reynolds, the co-executive director of the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, told the Times. A large portion of missing person cases "tend to involve white, middle-class women. And that resonates with assignment editors and news organizations," Reynolds added, though he noted that slowly increasing diversity among newsrooms has led to better coverage.

Also at play are disparate age cutoffs that help most police departments decide whether to "launch an immediate investigation" into a missing child, Nigel Roberts wrote for BET. There is no federal standard for these limits, resulting in "no immediate urgency when a mother in Louisville reports her 11-year-old daughter missing," Roberts added. "But state police in New Hampshire start searching right away if parents don't know the whereabouts of their 16-year-old minor." That said, investigators might override their state's cutoff if they believe a missing child is in immediate danger or has certain health complications that might complicate or impact the search. "That gives officers who initially interview the family enormous power," Roberts continued. "Their opinion of the child and the home environment – which can be shaded by racial bias – matters. Officers who believe certain stereotypes about Black children and their families could easily decide that there's no urgency to quickly investigate a missing Black child who's over the age limit."

What's next?

Data suggests things have been slowly improving, but there is still a long way to go. A report from the University of Wyoming found that 710 Indigenous Americans were reported missing between 2011 and September 2020, with most of them garnering little to no media coverage. Wyoming also happens to be the state where investigators found the remains of Gabby Petito, a white woman, after a search that dominated national headlines in 2021.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After analyzing data from the FBI and four "major online news sources," researchers at Northwestern University confirmed in a separate 2016 study that "there are, in fact, race and gender disparities consistent with Missing White Woman Syndrome," and that "they manifest themselves in two distinct ways: disparities in the threshold issue of whether a missing person receives any media attention at all; and disparities in coverage intensity among the missing persons that do appear in the news." The study found that Black people, in particular, were "significantly underrepresented" in media coverage.

Though researchers have grown more conscious of "Missing White Woman Syndrome" and diversified newsrooms are helping shed a light on missing minorities, the problem remains nonetheless.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

The Met police's stop and search overhaul

The Met police's stop and search overhaulThe Explainer More than 8,500 Londoners have helped put together a new charter for the controversial practice

-

'Warriors' vs 'guardians': the pitfalls of police recruit training in the US

'Warriors' vs 'guardians': the pitfalls of police recruit training in the USIN DEPTH American police training fails to keep pace with the increasingly complex realities that today's officers face

-

Can the Met Police heal its relationship with the Black community?

Can the Met Police heal its relationship with the Black community?In depth Police chiefs accused of not doing enough to address reported institutional racism

-

Met Police clean-up: more than 1,000 officers suspended or on restricted duties

Met Police clean-up: more than 1,000 officers suspended or on restricted duties'Eye-watering' figures show scale of challenge to restore public trust

-

DOJ investigating alleged racial profiling among Connecticut troopers

DOJ investigating alleged racial profiling among Connecticut troopersSpeed Read

-

Ohio residents demand justice after police officer kills family dog

Ohio residents demand justice after police officer kills family dogSpeed Read

-

What reforms can't fix

What reforms can't fixfeature The persistence of authoritarian police culture

-

6th Memphis police officer placed on leave in connection with Tyre Nichols' death

6th Memphis police officer placed on leave in connection with Tyre Nichols' deathSpeed Read