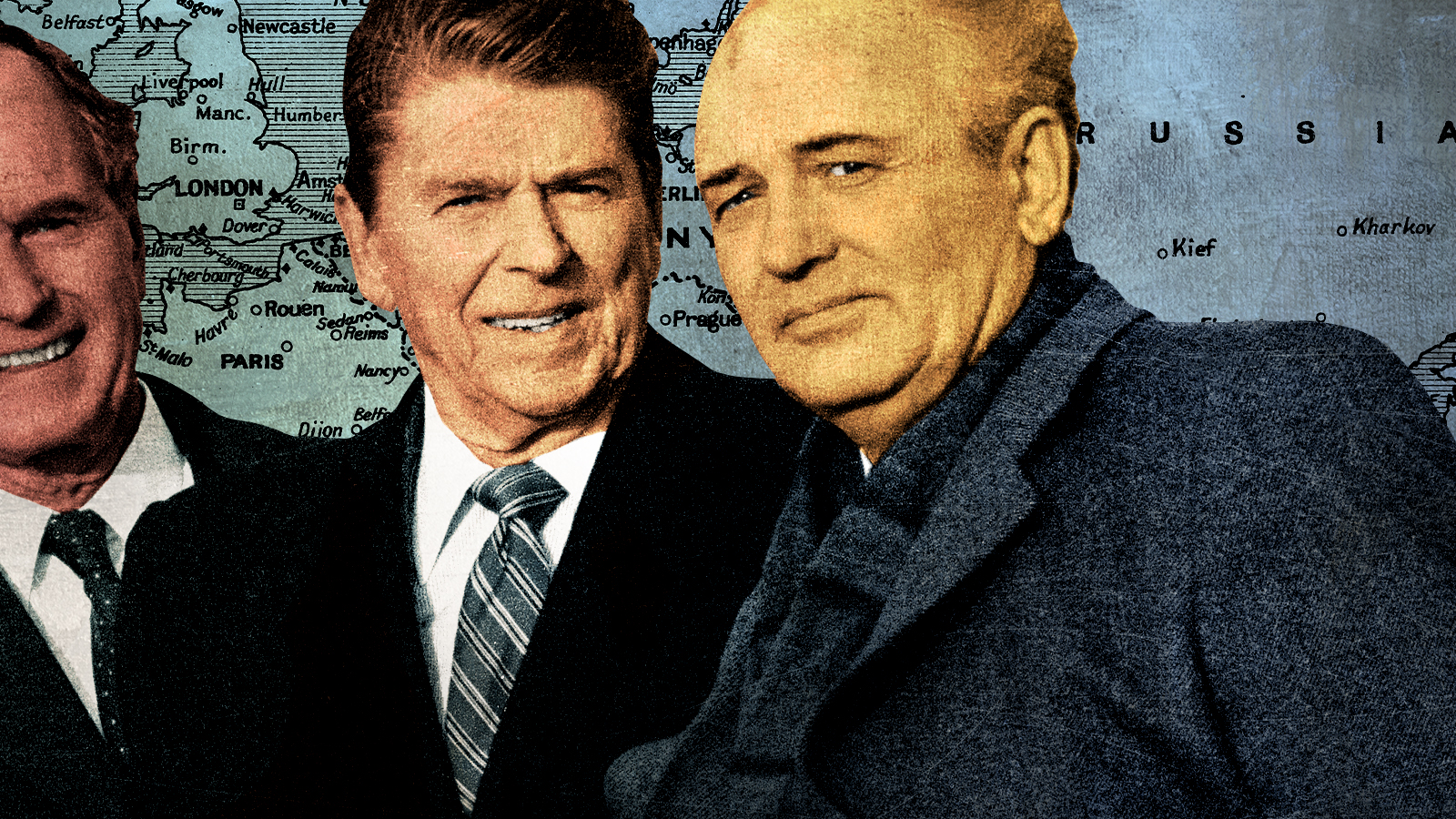

Gorbachev's complicated legacy

The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mikhail Gorbachev, the former Soviet leader credited with ending the Cold War and bringing about the collapse of the USSR, will be laid to rest on Saturday, after having died Tuesday at the age of 91. And though he's lauded in the West, public perception is a lot more complicated back home, where some (like Russian President Vladimir Putin) resent Gorbachev's trademark "glasnost" and "perestroika" reforms and their contribution to the demise of the Soviet empire.

Such a schism in mind, however, how might the last leader of the Soviet Union be remembered? What legacy does he leave behind? Leading publications tackle the question:

His legacy is nationalism

Gorbachev came to power just as the Marxist-Leninist Communist system was "unraveling," argued The Washington Post's Henry Olsen. And his reforms, though intended to make good on "the Soviet premise — global unity under one state —" ultimately just "gave rise to demand for more." Once "repressed" Soviet states gained independence, and "the totalitarian boot of communism was lifted, people reverted to their nationalist instincts," Olsen wrote.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Woodrow Wilson's old principle of self-determination, that every nation of people deserved its own state, became once more the organizing principle throughout the old Soviet empire," Olsen continued. Consequently, "resurgent nationalism is Gorbachev's real legacy for the modern world."

Such a resulting attitude isn't confined to the East, either; its influence can be felt in Western Europe, where most E.U. countries "now have a strong political party that is explicitly nationalist in tone and suspicious if not hostile toward globalism," and in the U.S., where it's disguised neatly inside right-leaning calls for "America First."

"We should be grateful that Gorbachev failed to save the Soviet Union, as it was truly an evil empire," Olsen argued. "History, however, did not end when the USSR fell. Instead, nationalism reasserted itself, with all the consequences that inevitably follow."

His legacy is hope

Yes, "Russia's post-Soviet experiment in democracy failed," opined The Guardian Editorial Board, "but the dream of its political freedom must be preserved." Though Gorbachev is, in some ex-Soviet states, "remembered more as a repressor of pro-independence movements than as a liberator," it's also true that not everyone feels as such. Some Russians see the "Putin cult" for what it is, and can recall the "reality of Soviet repression" without sharing in the nostalgia their president so proudly proclaims.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Some were too young to remember the advent of freedom in 1991, but wish it would dawn again," the Guardian mused. And "in them resides a hope that the idea of a democratic Russia is not buried with Mikhail Gorbachev."

He was too human

Bloomberg's Leonid Bershidksy struck a different tone with a tribute that did Gorbachev no favors, having opted to share his first-hand experience living under the rule of a "flailing, clueless loser, always one step behind the times" rather than a glowing memorial. Shortages, economic mismanagement … Gorbachev "thought he was bringing Communism closer to the people rather than dismantling it," Bershidsky recalled. Ultimately, he failed as both an autocrat and a politician — and Putin learned from those mistakes. In other words, Gorbachev didn't fail hard enough.

But there's one thing Bershidsky said he'll miss about the Soviet Union's final leader: "He was so bad at leading an evil empire because he was too obviously human." Unlike many contemporary leaders, Gorbachev was "carelessly emotional, incapable of keeping a poker face and — amazingly for a career party functionary — blind to intrigue." Such sensitivity is "a hindrance to political efficiency, of course. But it is perhaps why Gorbachev's attempt to hold together a malevolent enterprise failed."

He will be undone

"When Gorbachev left office in 1991," wrote Clara Ferreira Marques, also for Bloomberg, "he called on Russians to preserve the democratic freedoms he had introduced." But the "kleptocracy" that took over instead — one led, of course, by Putin, will now "weaponize his death."

As far as "Putin's political vision," few things are as consequential and significant as the unraveling of the USSR, for which he believes Gorbachev is responsible. And his death will not be treated as an opportunity to reflect on the weaknesses of the Soviet system, or the glow of Democracy. Rather, the Kremlin will use Gorbachev's failures as they seem to "justify empire-building actions today."

"These mistakes, Putin will say, cannot be repeated."

Brigid Kennedy worked at The Week from 2021 to 2023 as a staff writer, junior editor and then story editor, with an interest in U.S. politics, the economy and the music industry.