Why people fighting for their lives would stop to save a statue

The lesson in memory America can learn from Ukraine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Countless images coming out of Ukraine linger in my mind these days — fathers cradling their dead toddlers and pregnant women staring ashen-faced from stretchers and mothers filling sandbags together with their sons. These pictures are haunting and relentless, portraits of an embattled people fighting for their survival.

Rightly or wrongly, the cultural similarity between the U.S. and Ukraine has made this conflict feel more personal to me than those raging in Afghanistan or Myanmar. There's the McDonald's in the background of the bombed-out square. A robotic vacuum in the corner of one of the last photos a Kyiv man saw of his family still alive. My daughter's roller suitcase looks a lot like the one next to that crumpled body. My husband wears T-shirts like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Don't I have a jacket like the one that wailing mother is wearing? Don't I drive a car like that family has, the car with their handwritten placards, urgently announcing they're transporting children, plastered to the windows? I see the people huddled on mattresses in a subway station, underneath a sign announcing the music festival that was supposed to happen in Kyiv in late March — now a jarring reminder of life before. I wonder if any of them had planned to attend.

In each image, I see echoes of my life and how quickly it could all be stripped away. And yet, the single image that has given me the greatest pause isn't one of destruction at all. It's a photograph of a statue in Odesa buried underneath a mountain of sandbags.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I imagine all the people who filled those sandbags to encase the statue, passing them hand to hand down a line of determination and resolve. Even as Russian troops drew nearer with their indiscriminate bombs, this community set about trying to preserve its heritage.

I have tried to imagine how I might busy myself if I were preparing for missiles to fall from the sky. Though I'd like to think otherwise, I suspect I'd be mostly frozen in fear. It would be disingenuous to count myself among those who would visit local landmarks in my hometown to be sure their windows were boarded up and valuables tucked away.

And yet, I have an appreciation for those who do remember these things, too, are worth seeking to save. It touches something deep and tender within me to see a country trying to protect what others seek to destroy. It seems like a particularly hopeful act of defiance, a visual reminder to the invaders that Ukrainian humanity and ideals and history can't be conquered no matter what happens on the battlefield in coming weeks.

The image lingers with me, too, because it isn't always how cultures behave.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It was probably on my fourth or fifth visit to the Forbidden City when I first became aware of what I now think of as China's national museum's most peculiar trait: the paucity of artifacts. My family lived in China on the outskirts of Beijing for four years in the 2010s, and each time we had visitors from the United States, we dutifully took them traipsing through the Forbidden City. Wear comfortable shoes, I'd advise. And be ready to walk.

I'll be honest, it wasn't my favorite stop on the tourist circuit. It really did involve a lot of walking. After a while, to my untrained eye, the gates of the palace all started to look the same. And when I'd climb the steps to peer through windows, I'd find that in many cases, in lieu of actual artifacts, there were only pictures of artifacts. Then I presumed the treasures were kept elsewhere or on loan to museums around the world — and perhaps many were. But once, when I made an off-hand remark about it to a Chinese friend who'd joined us for the excursion, she quietly explained: "Our people destroyed a lot during the Cultural Revolution."

Across China, in a sweeping campaign that began in 1966 to rid the country of the Four Olds, millions were killed, tortured, and imprisoned. But the Cultural Revolution's zealots targeted material history, too. They smashed pottery, burned books, destroyed artifacts, and erased history in an attempt to rid their country of what they saw as archaic customs and ideas. As my friend explained, in many cases, historical structures themselves were preserved. But much of what you'd expect to find within them was destroyed, a monument of absence to a culture turning in on itself, cannibalizing its own history to make way for the future.

From that day forward, when I saw the framed pictures of Qing Dynasty pottery instead of the pottery itself, it felt like I was in a hall of mirrors. Here was a country trying to remember what it had tried to destroy. The Shard Box, an entrepreneurial Beijing family business, had my favorite solution to the problem: Specialists in taking fragments of smashed antique porcelain and repurposing them into beautiful boxes and jewelry, they create whole histories of empires rising and falling which can fit into your carry-on bag.

I do not tell these stories together to elevate one as morally superior while denigrating the other — or to call one culture noble and one ignoble. I know enough about human nature to know we all have a mix of both. And disparate circumstances mean the comparison only goes so far. But the two extremes have made me think about where my own country falls on this spectrum.

"One hundred and two Confederate symbols have been banished from public spaces in the nearly five months since [George] Floyd, a Black man, was killed at the hands of Minneapolis police," reported HuffPost in October 2020. More have come down since then. In my own community, one of the local high schools was renamed from Robert E. Lee High to Legacy High, a contentious decision I supported.

But it wasn't just honors for Confederate leaders that fell. Only public outcry kept San Francisco's school board from renaming schools titled after figures like Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln. A Teddy Roosevelt statue was removed from the Museum of Natural History in New York. And across the country, statues of lesser-known and less controversial figures have been vandalized.

Is this our own Cultural Revolution? The far right and left both say "yes," albeit in different senses. The far right would have you believe these actions are all the same — all efforts to rewrite history, to wrongfully discredit our country's past as hopelessly lost to the sins of racism. The far left takes up the revolutionaries' cry, insisting we must take down these statues to to atone, indeed, for a national past hopelessly lost to the sins of racism.

I think about this as I ponder the sandbags piled around the statue of Duke de Richelieu in Odesa. As the moments till his possible destruction ticked by, did local citizens debate the merits of his life and leadership? Did they discuss whether or not his memory deserved to be saved? Or did they bury him in sandbags simply because he was their history, believing this alone made his statue worthy of protection?

And what are we to do with our own contentious memorials? Should a Black child be educated in a school named to honor the Confederacy by a community that was angry about forced integration? I'd argue no. Should we tear down monuments of our first president because he was slave owner? I'd also argue no. Could the Roosevelt statue's controversial legacy of "patriarchy, white supremacy, and settler-colonialism" instead have been addressed by removing the flanking statues and adding a plaque of explanation? Perhaps.

I have no easy answers. I suspect, if we were honest, we'd admit none of us do, despite our often blustery insistence to the contrary.

I do know it's possible to remember a history without fostering nostalgia for its wrongs. "Germany has no monuments that celebrate the Nazi armed forces, however many grandfathers fought or fell for them. Instead, it has a dizzying number and variety of monuments to the victims of its murderous racism," wrote Susan Neiman for The Atlantic in 2019. Germany lives with tension in its history, and I suspect that collective memory is one reason Berlin was so quick to rally to Ukraine's cause.

We haven't learned to live with tension the same way here, but if we are to preserve the democracy we inherited, we must continue wrestling with the questions. The sand-bagged statue of Odesa is a reminder that there are other ways to hold our national memories. But it should also remind us that loss of liberty and loss of history have often gone hand in hand.

Carrie McKean is a writer who lives in Midland, Texas with her husband and two daughters. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times and Texas Monthly, among other local publications. You can find her on Twitter at @MckeanCarrie or at carriemckean.com.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Eurovision faces its Waterloo over Israel boycotts

Eurovision faces its Waterloo over Israel boycottsTalking Point Five major broadcasters have threatened to pull out of next year’s contest over Israel’s participation

-

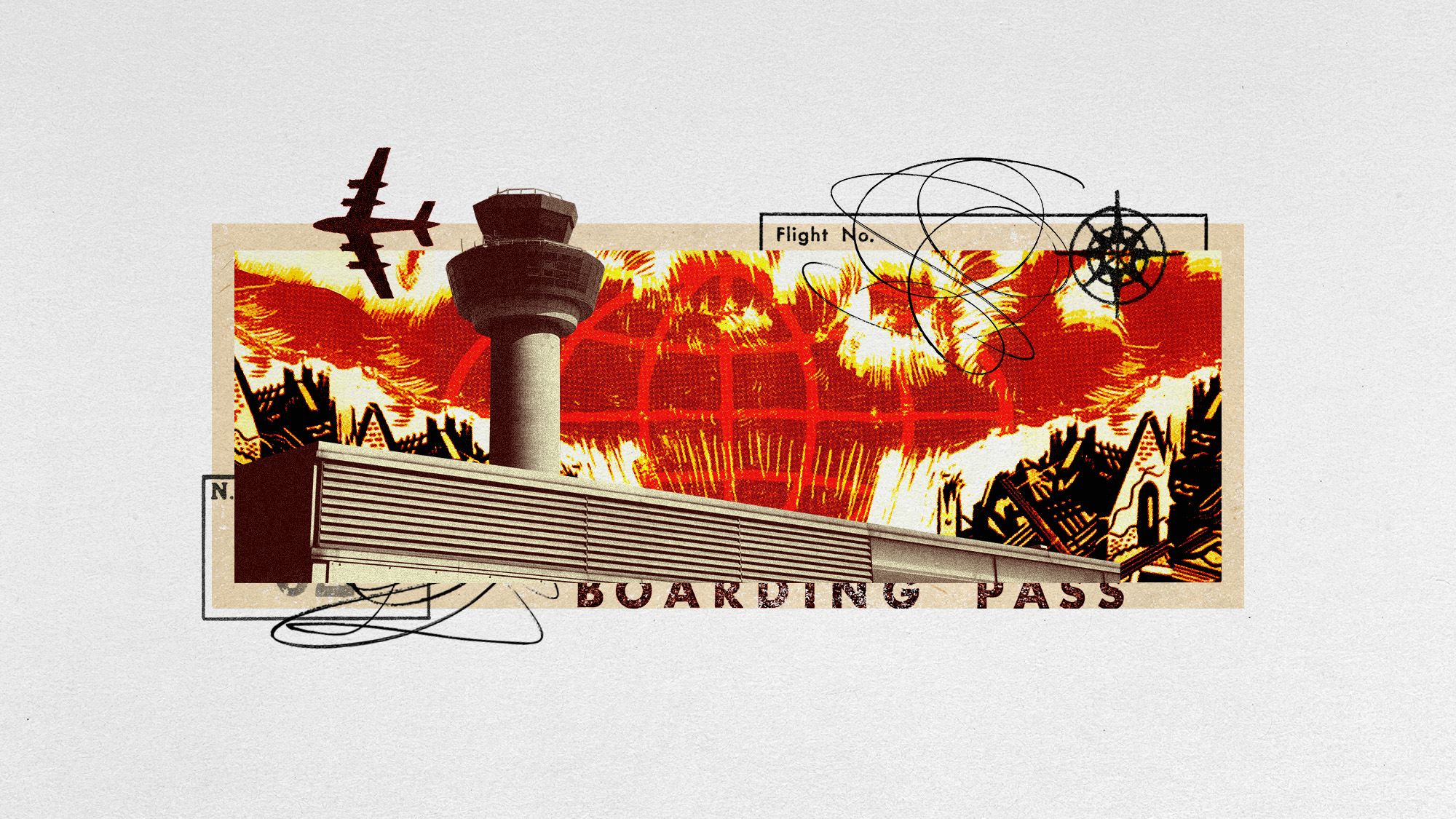

How global conflicts are reshaping flight paths

How global conflicts are reshaping flight pathsUnder the Radar Airlines are having to take longer and convoluted routes to avoid conflict zones

-

Sarah Rainsford shares the best books to explain Vladimir Putin's Russia

Sarah Rainsford shares the best books to explain Vladimir Putin's RussiaThe Week Recommends The correspondent picks works by Anna Politkovskaya, Catherine Belton and more

-

The Zelensky Story: as 'astonishing as it is inspirational'

The Zelensky Story: as 'astonishing as it is inspirational'The Week Recommends BBC Two's three-part documentary features 'genuinely revealing' interviews with the Ukrainian president

-

War tours: how tourism in Ukraine is bouncing back

War tours: how tourism in Ukraine is bouncing backUnder the Radar Visitors are returning to the war-torn country but not everyone is happy to see them

-

Eurovision 2024: how is politics playing out in Sweden?

Eurovision 2024: how is politics playing out in Sweden?Today's big question World's most popular song contest 'has always been politically charged' but 'this year perhaps more so than ever'

-

Will Elizabeth Gilbert's decision set a 'dangerous precedent' for book censorship?

Will Elizabeth Gilbert's decision set a 'dangerous precedent' for book censorship?Talking Point Her latest novel sparked backlash after she revealed it would be set in Russia.

-

Elizabeth Gilbert and the debate over cancelling Russian culture

Elizabeth Gilbert and the debate over cancelling Russian cultureTalking Point Decision to delay publication of novel set in 20th-century Siberia sparks intense debate