Peering at the edge of the universe

NASA is preparing to launch the most powerful space telescope ever. What will it see?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

NASA is preparing to launch the most powerful space telescope ever. What will it see? Here's everything you need to know:

Why a new space telescope?

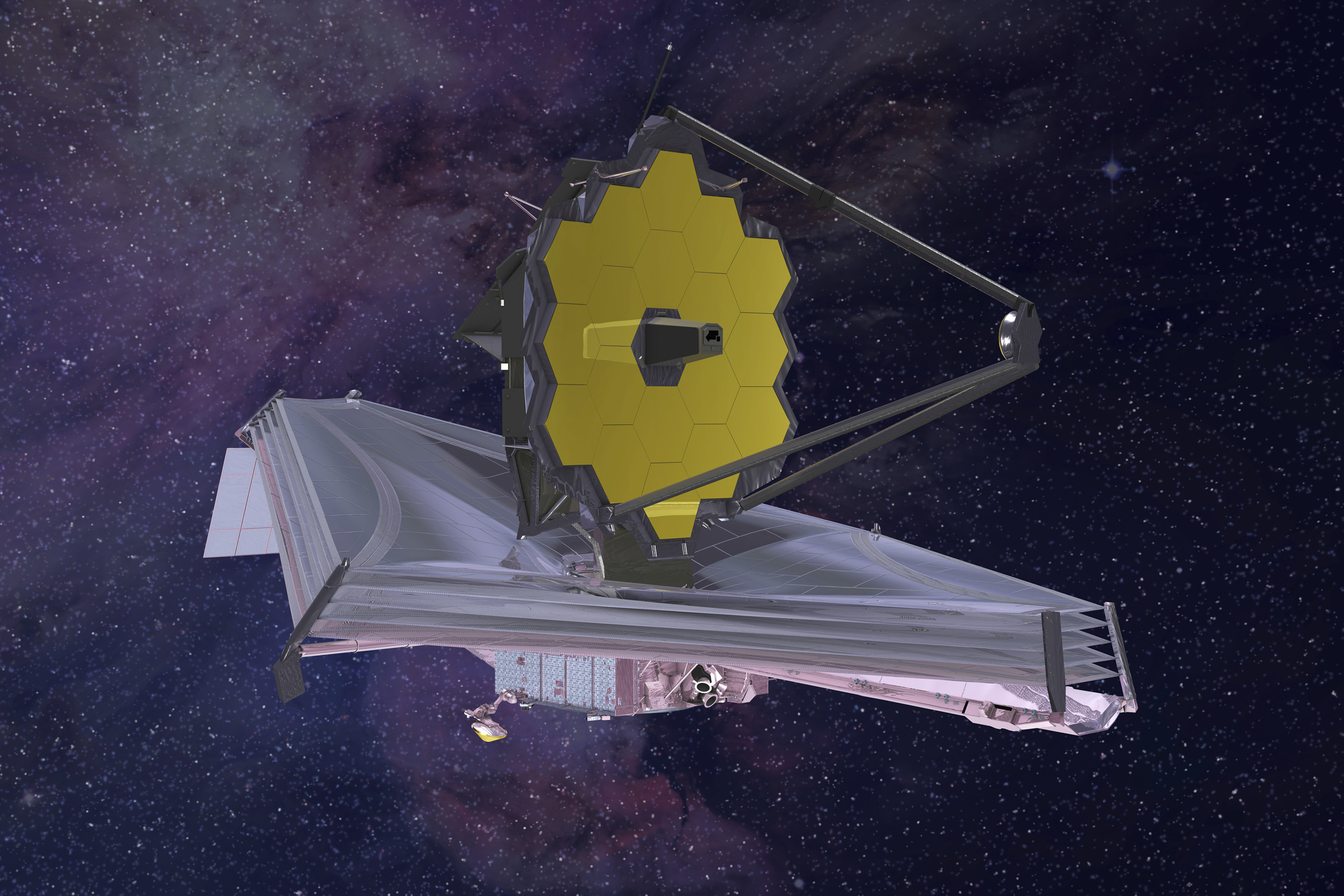

The James Webb Space Telescope will be 100 times more powerful than its predecessor, Hubble, and will be capable of capturing extremely faint infrared light from the very first galaxies at the edge of the universe. It will also be able to study planets around other stars in our own galaxy, examining their atmospheres for telltale signs of life. Originally scheduled to launch in 2010 and cost about $1 billion, Webb — a joint venture among U.S., European, and Canadian space agencies that took 10,000 people to construct — experienced a sequence of maddening delays as costs ballooned to $10 billion. But the colossal telescope finally has been shipped to French Guiana in South America, where it will be fitted onto a rocket and blasted into space on Dec. 18, beginning the most technically ambitious mission in NASA history. Should Webb successfully reach its destination nearly a million miles from Earth, the telescope will earn its nickname "First Light Machine," as it sends back images of stars formed just 250 million years after the Big Bang. "It's going to help us unlock some of the mysteries of our universe" and "rewrite the physics books," says Greg Robinson, Webb's program director at NASA.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does it work?

The telescope utilizes several novel technologies. It relies on a 21-foot mirror made of ultra-lightweight beryllium chiseled into 18 hexagonal segments and coated with gold. Unlike most telescopes, which house a mirror or lens within a tube to block out light, Webb's mirror will be exposed to open space, relying on five parasol-like sheets of aluminum-coated plastic — each as thin as notebook paper and as big as a tennis court — to block out light and heat from the sun, moon, and Earth. Webb includes four solar-powered cameras and sensors to collect data.

How does Webb differ from Hubble?

Hubble, launched in 1990, sent back dazzling images from deep space, and helped astrophysicists better determine the age of the universe, the nature of black holes, and the number of galaxies. It also led to the discovery that, thanks to "dark energy," the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate. That's where Webb comes in. By the time light from a 13 billion–year-old star reaches Earth, the expansion of the universe has stretched the light's wavelength into the infrared spectrum, similar to how a siren's pitch drops as an ambulance speeds away. For that reason, only an infrared-focused telescope is capable of peering into the "cosmic dawn." Webb uses mirrors that capture six times more light than Hubble's, and cameras with a 15-times-wider view. Hubble orbits the Earth at an altitude of 340 miles. Webb will be positioned out in space, roughly four times farther away from the Earth than the moon, for maximum light-gathering.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How does it get to space?

First, the 14,330-pound telescope must be folded, origami-style, to fit atop an Ariane 5 rocket. After about 30 minutes of flight, the telescope will be ejected from the rocket. "That's when the nail biting starts," says Heidi Hammel, a vice president at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. To open the sunshield, about 150 release mechanisms made up of 7,000 parts must fire correctly over the course of three days. On the seventh day, the primary mirror will unfold. "Those who are not worried or even terrified about this are not understanding what we are trying to do," says Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA's science office. After a roughly 30-day journey, Webb will reach Lagrange Point 2, where the gravitational tugs of the sun and Earth balance out, creating a convenient region for space telescopes to park. Webb will orbit the Sun, not the Earth.

What will Webb look for?

Answers to astrophysics' biggest questions. As it travels through space at 186,000 miles per second, light provides images on delay: The naked eye views the moon as it was 1.3 seconds ago, Jupiter as it was 40 minutes ago, and Andromeda — the nearest galaxy to ours — 2.5 million years ago. Space telescopes are often compared to time machines, collecting light emitted billions of years ago. Scientists believe Webb will be vital for studying the end of the Dark Ages — the period between the Big Bang and the formation of stars. That could reveal insights about the "dark matter" that makes up about 80 percent of the universe's mass. Webb can see back about 150 million years farther than Hubble, and thus may provide glimpses of the formation of the first stars, solar systems, and galaxies, says Caitlin Casey, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin. "With Webb," she says, "we're going right up to the edge of the observable universe."

Searching for signs of life

Recent breakthroughs in astronomy have established that most stars have orbiting planets, which means our galaxy probably hosts billions of these "exoplanets." Planets around other stars are too distant and dim to image clearly, but Webb can use its enormous capacity to gather infrared light to search the atmospheres of exoplanets for circumstantial evidence of extraterrestrial life, such as the presence of water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, methane, and other chemicals. One planetary system that Webb will study is about 40 light-years away: a small star called TRAPPIST-1, orbited by seven Earth-size planets — three of which orbit in the zone where temperatures could be mild enough for liquid water to form. Researchers are particularly excited to measure the methane and carbon dioxide in the fourth planet's atmosphere. "We all want to find another Earth, don't we?" said Kevin Stevenson, an astronomer at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. "Webb will provide us the first opportunity to really answer that question."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.