Detailed map of fly's brain holds clues to human mind

This remarkable fruit fly brain analysis will aid in future human brain research

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What happened

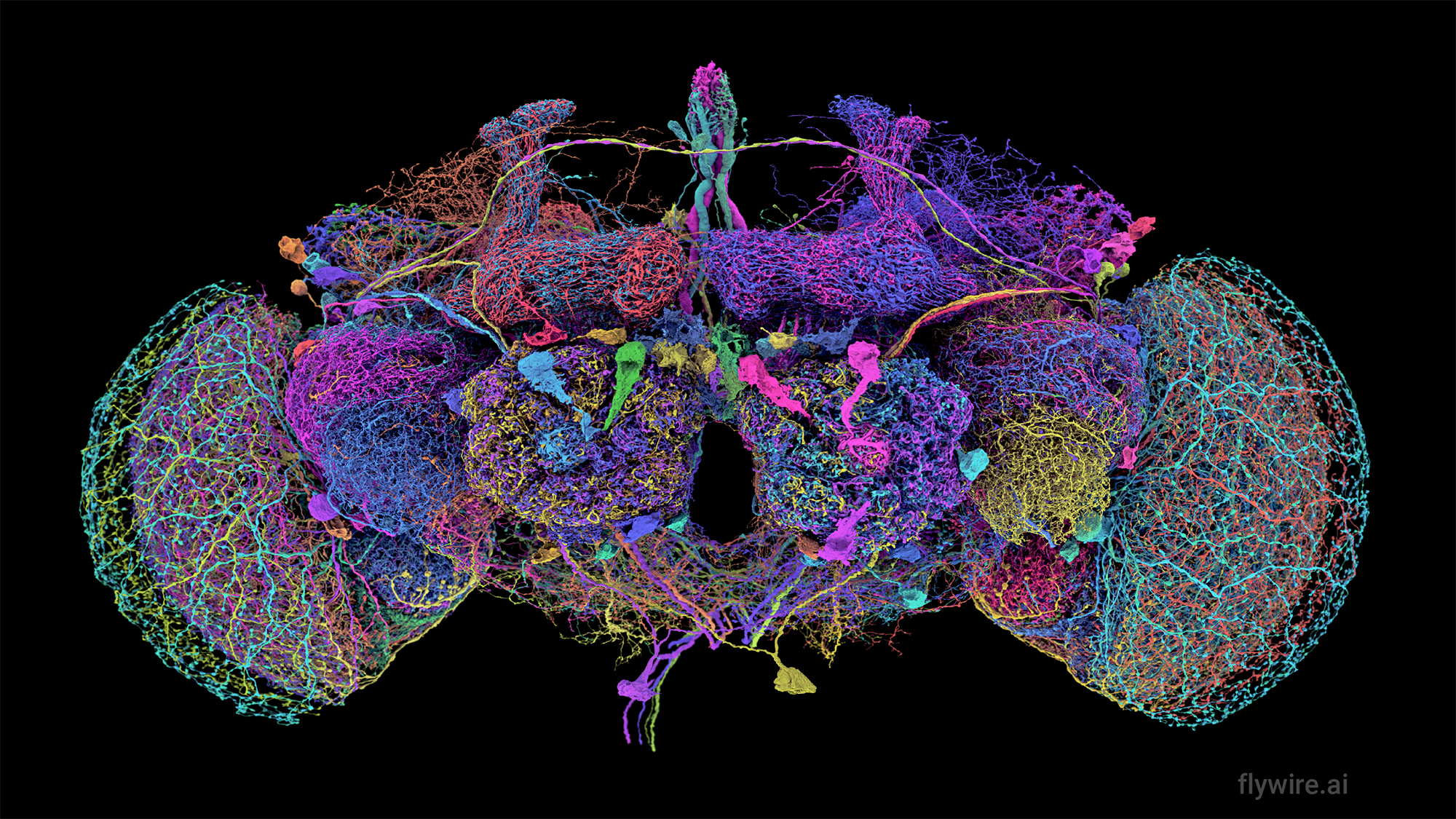

A consortium of scientists published the first complete map of a fruit fly's brain Wednesday in the journal Nature. Identifying and charting the 130,000 neurons and 50 million connections inside the poppy seed–sized brain of the fly, Drosophila melanogaster, took 10 years and involved hundreds of researchers worldwide.

Who said what

Scientists had mapped the 300-neuron brain of a tiny worm, but this is "the first time we've had a complete map of any complex brain," said Mala Murthy, a Princeton neurobiologist who helped lead the FlyWire project, to The New York Times. The "stunning detail" of the "tremendous complexity" packed into the fruit fly's tiny brain could "reveal principles that apply to other species, including humans, whose brains have 86 billion neurons," the Times said.

The "beautiful" and complex "tangle of wiring" mapped out in computer simulations may hold the "key to explaining how such a tiny organ can carry out so many powerful computational tasks," like sight, hearing and movement, the BBC said.

What next?

This "amazing technical feat" paves the way for mapping the neural pathways of "larger brains such as the mouse and, maybe in several decades, our own," brain researcher Lucia Prieto Godino of London's Francis Crick Institute said to the BBC. A mouse brain "contains about 1,000 times as many neurons as a fly," while the human brains has a million times more, the Times said, and scientists recognize that "bigger brains may not follow" the same "fundamental rules" for sending signals quickly across a fly's brain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

Russia’s ‘cyborg’ spy pigeons

Russia’s ‘cyborg’ spy pigeonsUnder the Radar Moscow neurotech company with Kremlin-linked funding claims to implant neural chips in birds’ brains to control their flight, and create ‘bio-drones’

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime