The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

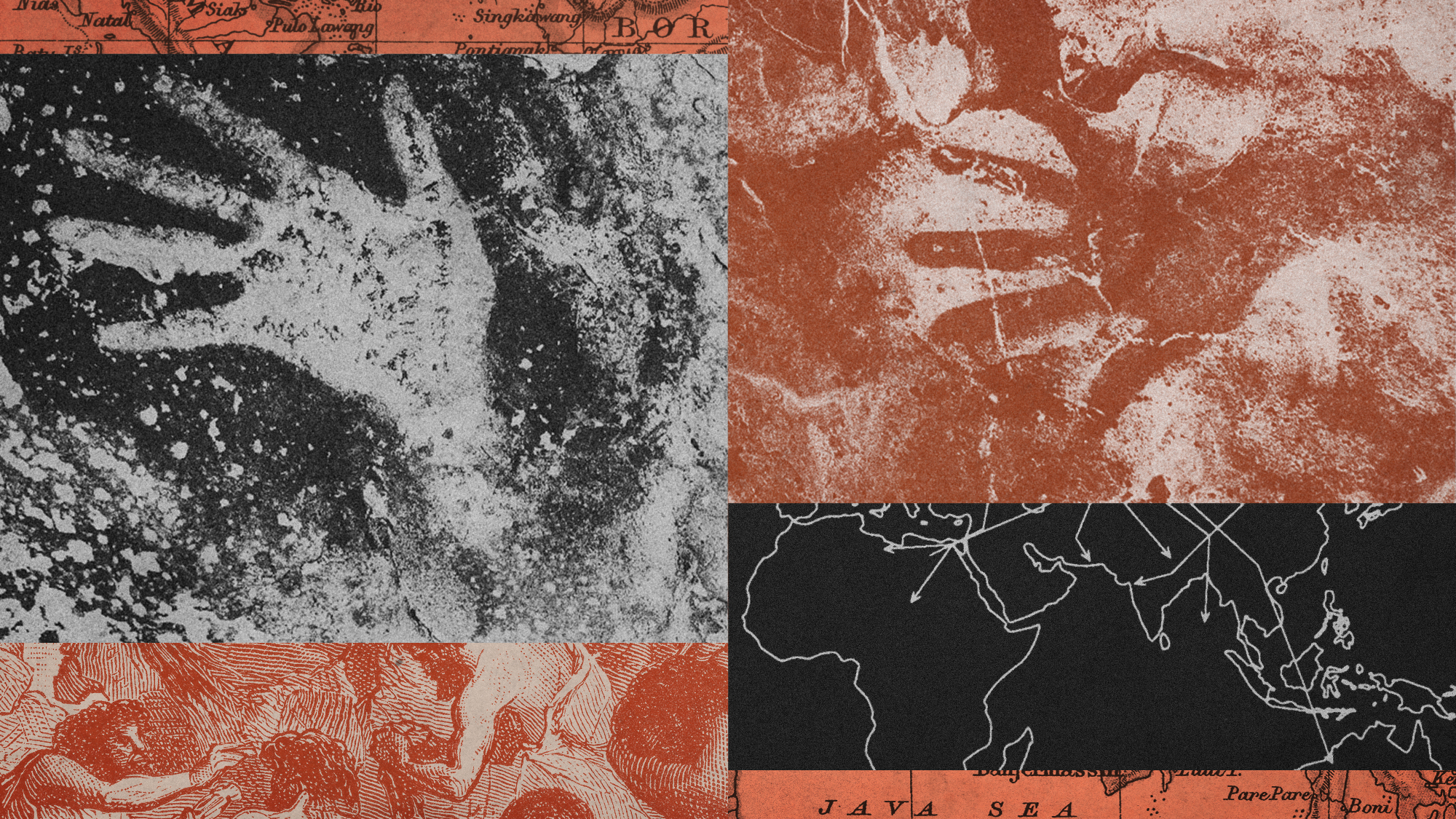

The recent discovery of rock art in a cave in Indonesia might signify more than just our ancestors’ artistic ability. The art, believed to be the oldest rock paintings ever discovered, dates back more than 67,000 years. But while the prints may provide clues about what these humans were doing, anthropologists say they may also give us an unprecedented look into early migration patterns.

Where was this rock art discovered?

Scientists found “figurative cave art and stencils of human hands” on two Indonesian islands in the Wallacea region, Sulawesi and Borneo, according to the study findings published in the journal Nature. The art from Sulawesi dates from at least 67,800 years ago; this finding predates the “archaeologists’ previous discovery in the same region by 15,000 years or more,” said Phys.org.

That the rock art was found in Indonesia isn’t too surprising, as the country is “known to host some of the world’s earliest cave drawings,” said The Associated Press, though even older cave art in South Africa has also been discovered. The art was likely made by “blowing pigment over hands placed against the cave walls, leaving an outline. Some of the fingertips were also tweaked to look more pointed.”

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is this art so significant?

Most research suggests humans “left Africa 60,000-90,000 years ago, walking through the Middle East and South Asia” before sailing toward the Australian landmass, and this art could “hold important clues to the story of this epic human migration,” said National Geographic. The rock art finding crucially supports research that early humans “had seafaring technology and were capable of open water crossings between Wallacea and Australia by 65,000 years ago,” said Helen Farr, a maritime archaeologist at the U.K.’s University of Southampton, to National Geographic.

It is “great to see the art preserved and dated, providing a small window to a wide range of activities that’s often missing in the [archaeology] of this time depth,” said Farr to National Geographic. Since sea levels were “much lower at the time, land bridges opened up between some neighboring islands, but humans would still have needed to island hop to spread across the region,” said The Guardian, and the rock art provides insight as to how this may have occurred.

The findings also give a glimpse into early human intelligence, experts say. Researchers previously studying cave art in Europe often “thought, ‘Wow, this is really where true art began, true modern human artistic culture,’” Adam Brumm, a professor of archaeology at Australia’s Griffith University and a co-author of the study, said to NBC News. But the new discovery proves humans were making “incredibly sophisticated” cave art “before our species ever even set foot in that part of the world.”

The findings in Indonesia are “probably not a series of isolated surprises, but the gradual revealing of a much deeper and older cultural tradition that has simply been invisible to us until recently,” Maxime Aubert, a professor of archaeology at Griffith University and another co-author of the study, said to CNN. But other human-like species besides Homo sapiens were also known to inhabit the area at the time, and some researchers urged people to take the findings with a grain of salt. Before “writing grand narratives about the complexity and success of Homo sapiens we really should consider other, potentially more interesting explanations of this fascinating phenomenon,” Paul Pettitt, a professor of palaeolithic archaeology at the U.K.’s University of Durham, said to CNN.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.