Scottish independence: The economic challenge

The arguments aren't very different from the first referendum in 2014 – but after Brexit, who knows what might happen?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

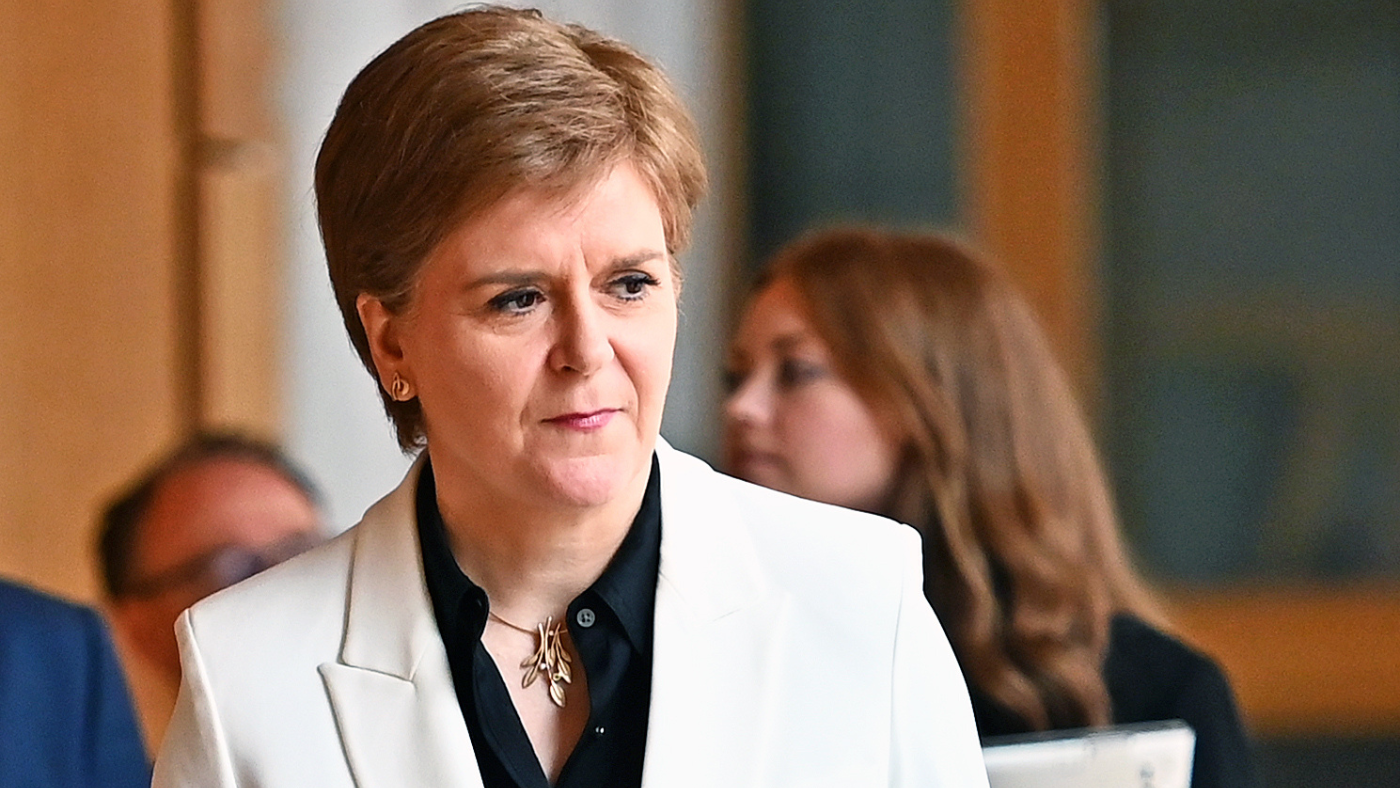

Scotland's nationalist leaders will face tough questions over how the country's economy could withstand independence following Nicola Sturgeon's call for a second referendum on leaving the UK.

What happened?

Scotland's First Minister said on Monday she would seek permission to hold a second independence referendum in either 2018 or 2019, once the terms of Brexit become clear.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Wasn't this issue settled in 2014?

So it seemed. All sides agreed before the September 2014 independence referendum that it would settle the issue "for a generation". The Scottish National Party itself described the vote as a "once in a lifetime" opportunity.

However, the pro-union camp used the country's membership of the EU in its case for Scotland staying part of the UK and the SNP now argues that as the UK has voted to leave the bloc and the Tories are pursuing a hard Brexit, the situation is completely different.

Sturgeon is also angry that Theresa May refused to compromise on allowing devolved administrations a vote on a final Brexit deal. Remember, more than six in ten voters in Scotland backed Remain last June.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sounds compelling.

It is – and there is some limited polling evidence that support for independence is edging up, albeit still stuck at around 50 per cent.

That being said, a YouGov poll published in The Times following Sturgeons' announcement found a 14-point lead for Scotland staying in the union once "don't knows" were excluded, taking the result to 57 per cent to 43 per cent.

"YouGov last recorded a 14-point lead in favour of Scotland staying in the Union in a poll in August 2014, a month before the first independence referendum," says the Times.

The problem for Sturgeon is the economic arguments that derailed the first independence bid still stand. In fact, The Guardian says, "constructing an economic case for independence looks harder now than it did three years ago".

What is the problem?

In 2014, "to make the sums add up, those advocating independence assumed an oil price of $100 a barrel", says the Guardian.

However, oil has slumped since then and now stands at around half that level. According to the Daily Telegraph, the Scottish government had estimated earning £1.8bn in tax revenue from its critical North Sea oil industry last year, but took a mere £60m.

In part as a result of this, Scotland's economic growth is lagging behind the rest of the UK, standing at 0.7 per cent compared with two per cent for the country as a whole last year.

More critically still, especially if Scotland wants to become an independent member of the EU, Holyrood's welfare spending is far higher than the rest of the UK and it is running a budget deficit, based on its own estimates, of 9.5 per cent.

That's around three times the UK shortfall and would be the worst in the EU – worse even than Greece. As new EU members have to pledge to get their deficit below three per cent, that suggests swingeing spending cuts would be needed.

Finally, splitting from the UK would mean divorce from the country to which Scotland currently sends almost two-thirds of its exports.

What about the pound?

Yes, that was another critical issue at the 2014 vote and it remains unresolved.

The SNP advocated keeping the pound, but that was ruled out by the Bank of England. EU rules state an independent Scotland should join the euro, something a majority of the country has consistently opposed.

Either way, the Guardian adds, Scotland would be using a foreign currency and have no control over its interest rates, which means it cannot devalue to offset the severe economic headwinds that might result from independence.

Sounds like the economic case is doomed?

Not necessarily. As the Guardian says, "Scotland has some real economic strengths".

As well as "a thriving financial sector", the country is "strong in food and drink, attracts millions of tourists each year and has the potential to be a world leader in renewable energy", adds the paper.

If it kept membership of the EU and its single market, Scotland would also become a very attractive home for those financial services firms in London currently considering their future post-Brexit.

That could form the basis of a new economic case for independence.

So Scotland might benefit outside the UK?

It's definitely possible. A big hurdle, however, could be whether or not independence-supporting Scots really want to join the EU as a standalone country, with all the loss of UK perks that might entail.

The Daily Telegraph points out that 400,000 Scots who backed independence are estimated to have voted Leave last June, equating to about a quarter of all those who backed the Yes campaign.

In addition, the government's own Scottish Attitudes Survey found more than two-thirds of people north of the border are either anti-EU or at least want to see its power curbed.

One SNP source even told the paper that Sturgeon will drop the idea of rejoining the EU in favour of seeking to join the European Free Trade Area, like Norway. That would still enable the country to remain in the single market, which could be critical to the independence case.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What currency would an independent Scotland use?

What currency would an independent Scotland use?In Depth An informal adoption of sterling is likely to be Scotland’s only route to keeping the pound

-

The road to a second Scottish independence referendum

The road to a second Scottish independence referendumfeature Nicola Sturgeon launched her latest bid for Scottish independence last week

-

What Scotland can learn from Irish independence

What Scotland can learn from Irish independencefeature Economists predict Scottish transition would fail to curb increasing interest rates and inequality

-

Scottish independence: Budget deficit raises £13bn question

Scottish independence: Budget deficit raises £13bn questionSpeed Read A massive black hole in the Scottish finances has been seized upon by unionists

-

Scotland runs up deficit twice the size of UK total

Scotland runs up deficit twice the size of UK totalSpeed Read Unionist MPs say Holyrood overspend of £14.9bn underlines how financially damaging independence would have been