Courts are increasingly granting police immunity in excessive force cases

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Qualified immunity has become a big concern as conversations grow surrounding police reform. And as Reuters reports, use of the controversial court doctrine has only grown as well.

The Supreme Court created qualified immunity in 1967 to protect police officers who acted in "good faith" but violated the Constitution while working in an official capacity. It lets courts stop victims of police brutality from suing officers, even over an unconstitutional act, unless their actions were "clearly established" to be unconstitutional beforehand.

To decide whether to grant a police officer's request for immunity, courts first ask whether a jury could find an officer violated the Fourth amendment and used excessive force. Courts said yes to that question in more than half of appellate cases from 2015-2019 that Reuters analyzed. But as of 2009, courts can also skip the first question altogether, and have been doing so more and more often.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Next up, courts ask whether an officer should've known the violation was unconstitutional because it was established by a previous case. If that's a yes, the case goes to trial. But if not, the office receives immunity and the case doesn't even go to a jury. That's what has happened in more than half of cases from 2015-2019, Reuters reports.

Reuters goes on to note that granting immunity is actually a growing trend. From 2005-2007, courts actually favored plaintiffs 56 percent of the time in excessive force cases. But from 2017-2019, that trend has reversed, and courts favor police 57 percent of the time. This growing reality has lawyers, civil rights advocates, politicians, and even Supreme Court justices worried the doctrine has "become a nearly failsafe tool to let police brutality go unpunished and deny victims their constitutional rights," Reuters writes. Read more at Reuters.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kathryn is a graduate of Syracuse University, with degrees in magazine journalism and information technology, along with hours to earn another degree after working at SU's independent paper The Daily Orange. She's currently recovering from a horse addiction while living in New York City, and likes to share her extremely dry sense of humor on Twitter.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

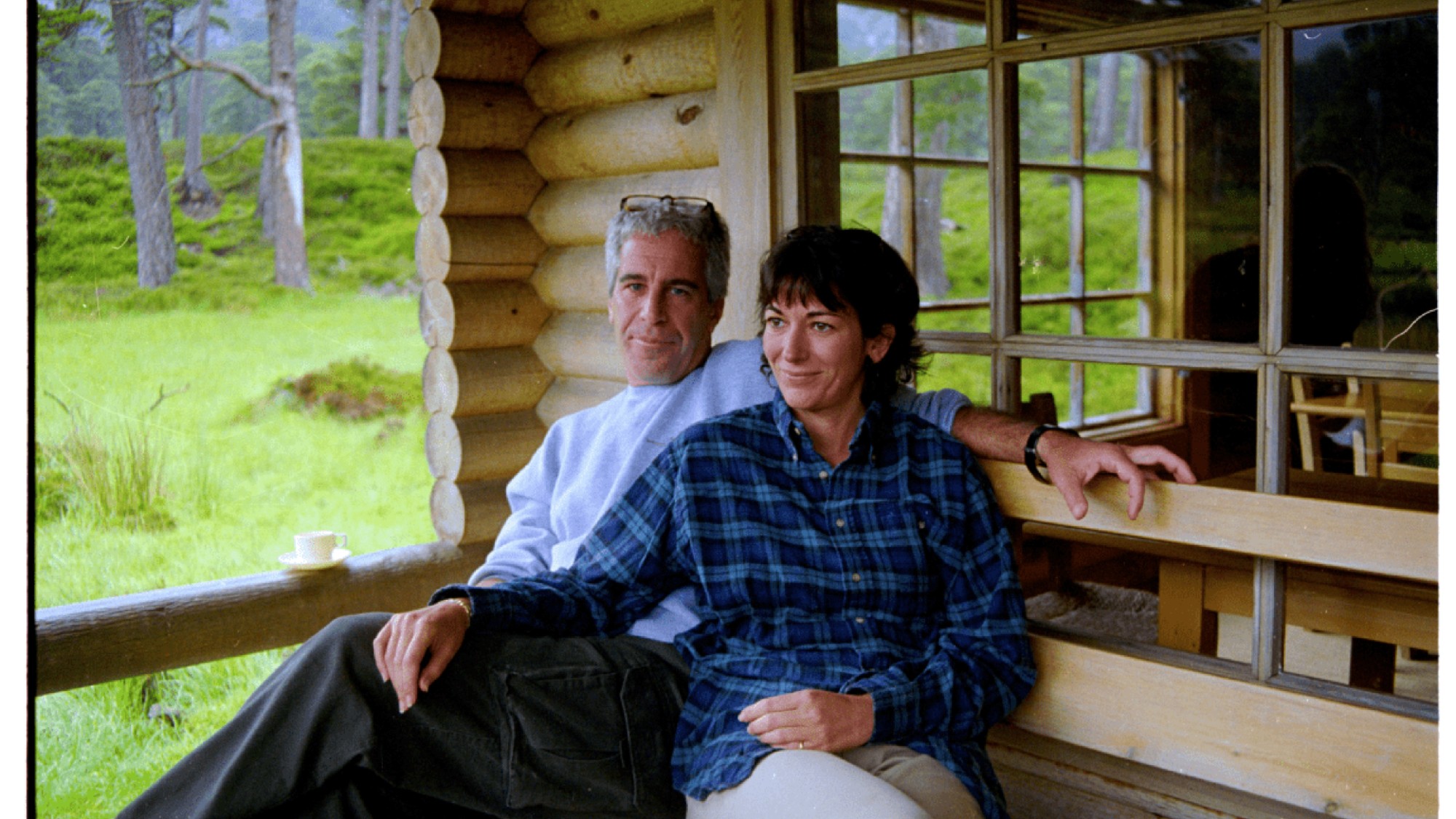

Maxwell pleads 5th, offers Epstein answers for pardon

Maxwell pleads 5th, offers Epstein answers for pardonSpeed Read She offered to talk only if she first received a pardon from President Donald Trump

-

Hong Kong jails democracy advocate Jimmy Lai

Hong Kong jails democracy advocate Jimmy LaiSpeed Read The former media tycoon was sentenced to 20 years in prison

-

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murder

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murderSpeed Read Sean Grayson was sentenced for the 2024 killing of Sonya Massey

-

Sole suspect in Brown, MIT shootings found dead

Sole suspect in Brown, MIT shootings found deadSpeed Read The mass shooting suspect, a former Brown grad student, died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds

-

France makes first arrests in Louvre jewels heist

France makes first arrests in Louvre jewels heistSpeed Read Two suspects were arrested in connection with the daytime theft of royal jewels from the museum

-

Trump pardons crypto titan who enriched family

Trump pardons crypto titan who enriched familySpeed Read Binance founder Changpeng Zhao pleaded guilty in 2023 to enabling money laundering while CEO of the cryptocurrency exchange

-

Thieves nab French crown jewels from Louvre

Thieves nab French crown jewels from LouvreSpeed Read A gang of thieves stole 19th century royal jewels from the Paris museum’s Galerie d’Apollon

-

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 years

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 yearsSpeed Read Cody Balmer broke into the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion and tried to burn it down