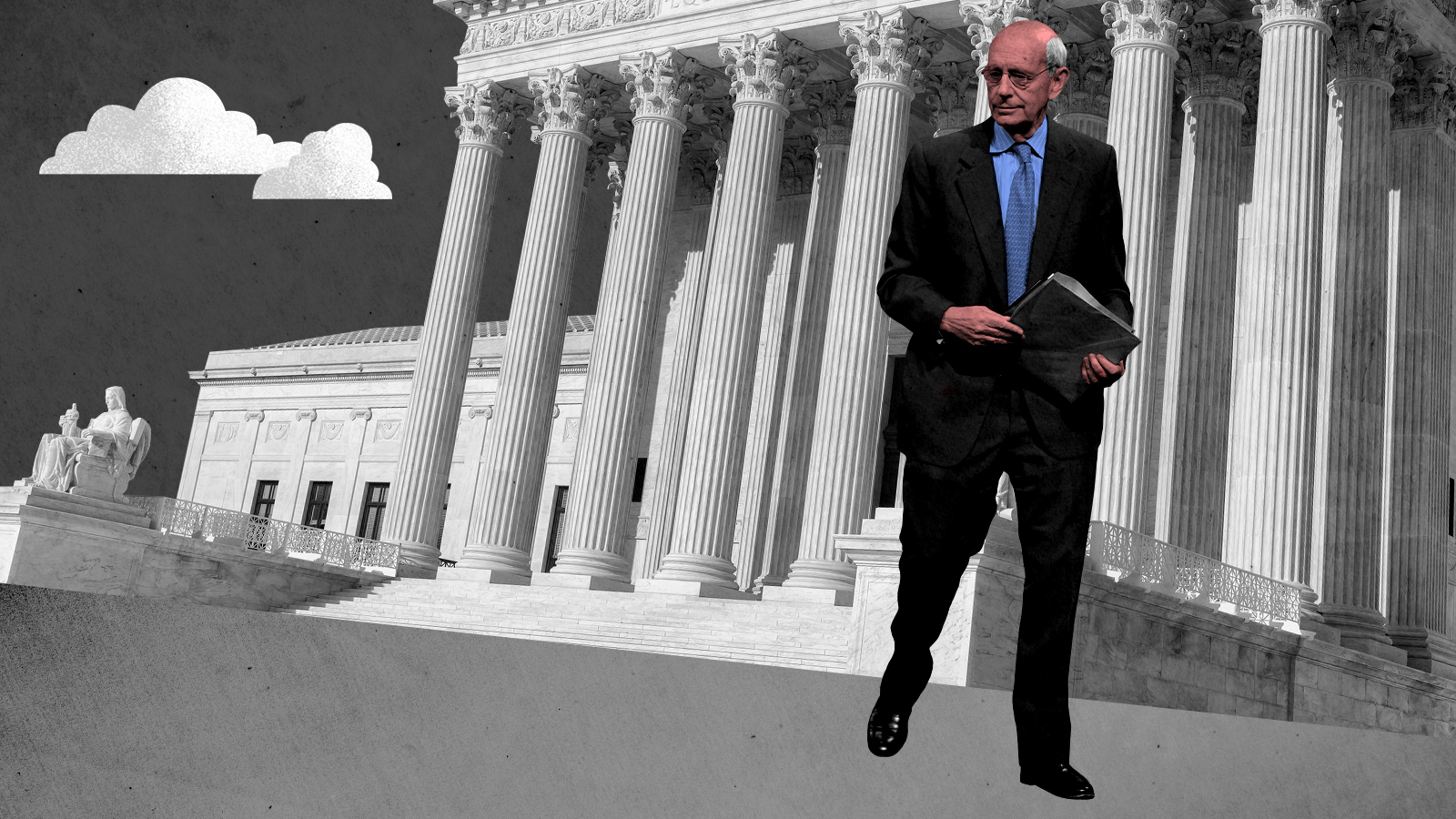

The best replacement for Stephen Breyer is Stephen Breyer

The retiring justice's humble judicial philosophy can preserve the court's legitimacy and woo its center-right bloc

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

So Justice Stephen Breyer is retiring after all.

The gnashing of teeth and rending of garments on both the left and center-left about his irresponsibility probably only served to firm up his conviction that he had to stick around until the noise died down so as not to politicize what is, ultimately, an entirely sensible decision independent of any hope he might harbor of being replaced by someone ideologically similar to him.

That hope, though, is something Breyer's critics on the left ought to share more than they do. Regardless of who President Biden chooses to replace Breyer, the reality is the Supreme Court will have a conservative majority for a long time to come. In that context, the most important job of a Biden appointee will not be to join the court's other two liberals in blistering dissents but to influence the persuadable justices on the right to chart a middle course that could preserve the court's legitimacy by reducing its political profile.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In other words, Biden should be looking for a justice like Stephen Breyer.

Of all the liberals on the court, Breyer is by far the most sensitive to what legal scholar Alexander Bickel called the counter-majoritarian difficulty. Why should an unelected court, representing the political preferences of earlier majorities, be allowed to overrule the majority that currently exists? Granting that there is inevitably a role for the court in clarifying ambiguous language and adjudicating between the branches of the government, why shouldn't the people themselves — acting through their elected representatives — be the best and final interpreters of the deliberately open and equivocal phrases of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the key post-Civil War amendments?

Breyer had some sympathy with this perspective and for that reason was distinctly more reluctant than his colleagues to overturn acts of Congress or impose new limits on the executive branch. His principled objections to originalism and textualism — the two predominant philosophies advanced by judicial conservatives — were that they were insufficiently attentive to the purpose of legislation or to making democracy work in practice.

From Breyer's perspective, the court's job is not merely to say "what the law is," as Chief Justice John Marshall put it, but to help the law make sense, and to do so in a manner that makes government both more accountable and more functional. The court, in other words, should properly be the handmaiden of the political branches rather than their overseer.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For liberals raised on memories of the heroically liberal Warren Court, or who cherish their "notorious RBG" merchandise, such a vision may seem like a come-down. But it is precisely the humility of Breyer's vision that gives it lasting power — and a chance of wooing support from the court's center-right.

Concern about judicial overreach was a major spur to the conservative judicial movement at the time of its formation. Today, with a substantial right-wing majority, there's at least as much risk of that overreach coming from the right as from the left. Not only its liberal wing but the court itself would benefit from a liberal justice who can join with Chief Justice John Roberts and other center-right members of the court in avoiding that temptation.

Moreover, Breyer's emphasis on the court's special role in not only safeguarding but nurturing democracy is much needed on the court today. In his book, Active Liberty, Breyer argued that when the court is activist, it should be on the side of facilitating the engagement of the citizenry in the process of democracy.

In trying to harmonize ancient and modern conceptions of liberty, his thinking has roots in John Dewey and Hannah Arendt and provides a basis for dialogue with as well as a response to an emerging so-called "common good" conservatism. But it is also a rebuke to a court that was willing to overturn an act of Congress protecting voting rights but repeatedly unwilling to intervene to limit partisan gerrymandering that systematically undermines democratic accountability. If the liberals on the court are going to pick their battles, this is the right one to pick.

A more deferential judicial liberalismwill not deliver all the results political liberals would like. The Supreme Court is soon due to hear cases on abortion, affirmative action and gun rights. A deferential and restrained court would be neither consistently liberal or consistently conservative across these cases — and Breyer himself will likely be more consistently liberal than consistently deferential to the duly-elected legislatures in these cases. But a liberalism that can articulate clear and comprehensible limits to its own activism would do far more to lay a strong foundation for a future, more liberal majority and to preserve the court's legitimacy in the meantime.

That's what Justice Breyer argued for his entire career on the court. If Biden wants to actually make a positive contribution to American jurisprudence and not just play to the liberal gallery, he'll choose a replacement capable of carrying that argument forward.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal