Is independence on the horizon for Quebec?

French-speaking territory elects an outspoken separatist party but the appetite for independence remains low. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This week, Canada’s federal election saw voters in the French-speaking province of Quebec mostly abandon Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, weakening his mandate and leaving him barely clinging to power.

But while pundits questioned Trudeau’s ability to command a government in such a divided country, a more intriguing facet of the election is who the people of Quebec opted for instead: Bloc Quebecois, a left-wing nationalist separatist party that has long called for total independence from the rest of Canada.

Listen to "#146 Quebeckers, millionaires and autobahns" on Spreaker.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

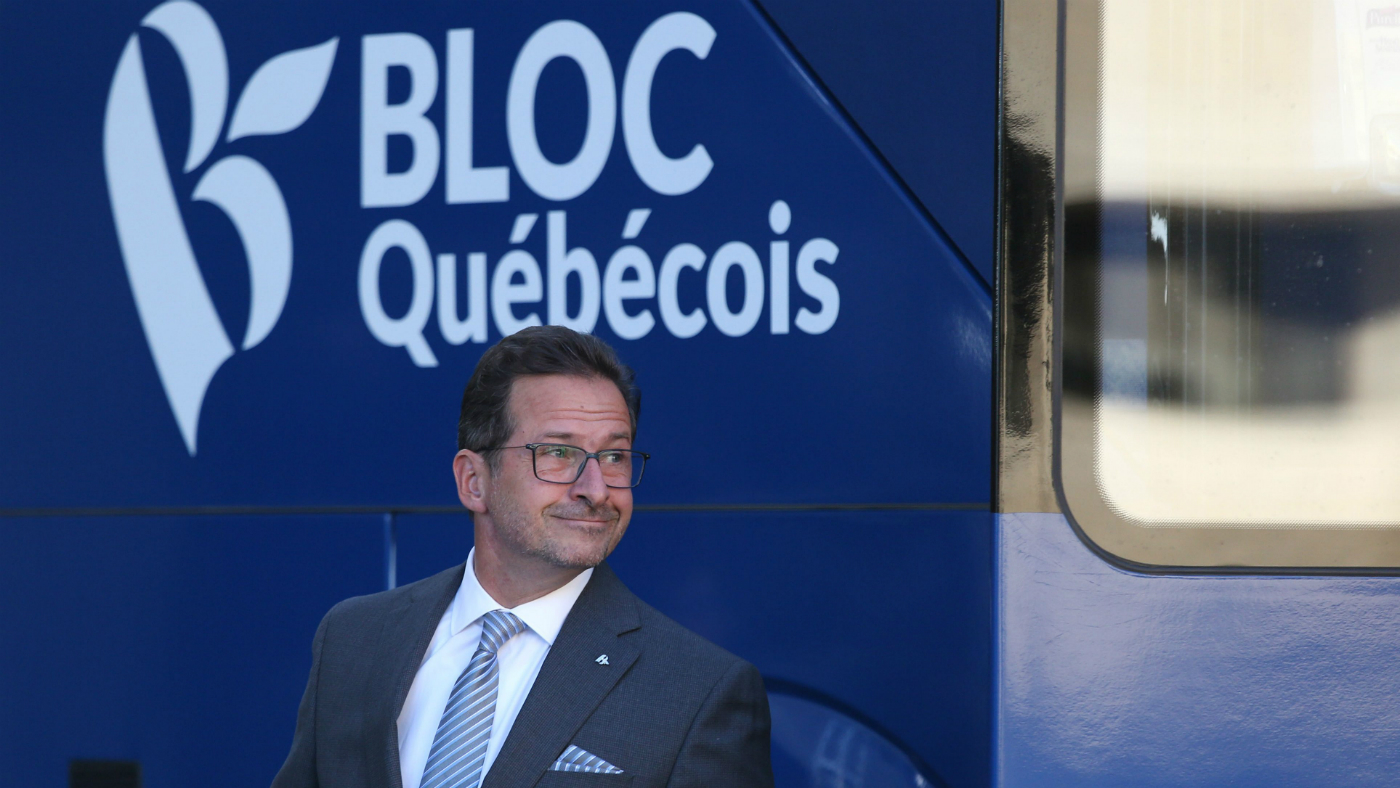

Under the leadership of Yves-Francois Blanchet, the Bloc, which was mostly wiped out in Quebec during the 2015 election by a wave of support for Trudeau, has enjoyed a major resurgence. It more than tripled its seats in Canada’s House of Commons, increasing its tally from 10 to 32 and overtaking the New Democratic Party (NDP) to become the third biggest party.

Prior to the election, both the Liberals and the Conservatives warned that returning more Bloc Quebecois MPs to Ottawa would result in another independence referendum in Quebec, and the surge in popularity for Bloc certainly looks like it spells trouble for Trudeau.

But experts have expressed doubt over the region’s true appetite for separatism, with The Globe and Mail noting that “Quebec independence remains deeply unpopular, both in polls and as reflected in recent provincial elections”.

What’s the history behind Quebec independence?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Separatism in Canada is a term commonly associated with various movements or parties in the French-speaking province of Quebec since the 1960s. The most notable are the Parti Quebecois, which contests elections at the provincial level, and the Bloc Quebecois, which contests federal elections. The two parties share close ties but are not officially linked.

According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, popular support for separatism in Quebec and for the organisations that represented it “rapidly increased in the province in the late 1960s and the 1970s”, but it lost momentum after a heavy defeat in a referendum in 1980.

But after a controversial fallout between Quebec lawmakers and Ottawa in 1982, a second referendum in 1995 saw the province come within just 60,000 votes of opting for independence. This was arguably the last chance for Quebec to opt for independence, and the appetite for separatism has declined ever since.

The Globe and Mail says the Bloc still supports independence, as it did when it dominated the Quebec electoral map from 1993 to 2011, but says it “did so quietly in this election campaign”. Instead, the party concentrated on a raft of environmental and progressive measures, including a promise to oppose any oil pipeline development through the province.

Do the people of Quebec want independence?

In the last large-scale opinion poll held in late 2016, 82% of Quebec respondents to a survey conducted by the CBC agreed with the statement: “Ultimately, Quebec should stay in Canada.”

“Quebeckers want a strong Quebec nationalism, within Canada,” pollster Jean-Marc Leger told The Globe and Mail. “They want to stay in Canada, but they do not want to be told what to do. The rise of the Bloc is not the rise of sovereignty.”

As a result of this swing away from full sovereignty, Blanchet appears to be hinting at more autonomy, telling reporters shortly before the election: “If it’s good for Quebec, we’ll vote for; if it’s bad for Quebec, we’ll vote against; and in between, we’ll negotiate. We can have very cordial relations. If Canadians and Quebeckers send a mosaic to Parliament, maybe it’s what they want. Maybe they want that kind of collaboration.”

“Our job is not to make Canadian federalism work. Our job … is also not to cause problems,” he added.

Nevertheless, despite opinion being against them, the National Post suggests that Bloc and its paying members may be “hoping gains made Monday will eventually lead to a resurgence of a Quebec independence movement”.

So why did so many people vote for the Bloc?

The Independent suggests that although it was remarkable that the Bloc has “returned from the dead”, the party’s revival “reflects a broad dissatisfaction with the political status quo rather than any renewed taste for separatism, the support for which is at an all-time low”.

More specifically, Rabble.ca reports, the Bloc was a “convenient place for Quebecers unimpressed by Trudeau’s commitment to the French language or to Quebec identity, or to contracts for Quebec shipbuilding or to support for SNC-Lavalin employees and pensioners, to park their votes”.

But if the defection of Quebecois to the Bloc was designed to be a harsh wake-up call to Trudeau, it doesn’t appear to have worked. Shortly after his re-election, he raised eyebrows by announcing that “from coast to coast to coast, tonight Canadians rejected division”.

Seeing as the controversial PM had barely clung to power with a weakened mandate, not everyone was receptive to his message of unity. “No sorry, Prime Minister,” David Akin, the chief political correspondent for Global News, said in the wake of the speech. “This is a divided country: the west is blue, Ontario is pretty much red, Quebec has just elected a bunch of separatists and you’re the guy in charge.”

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

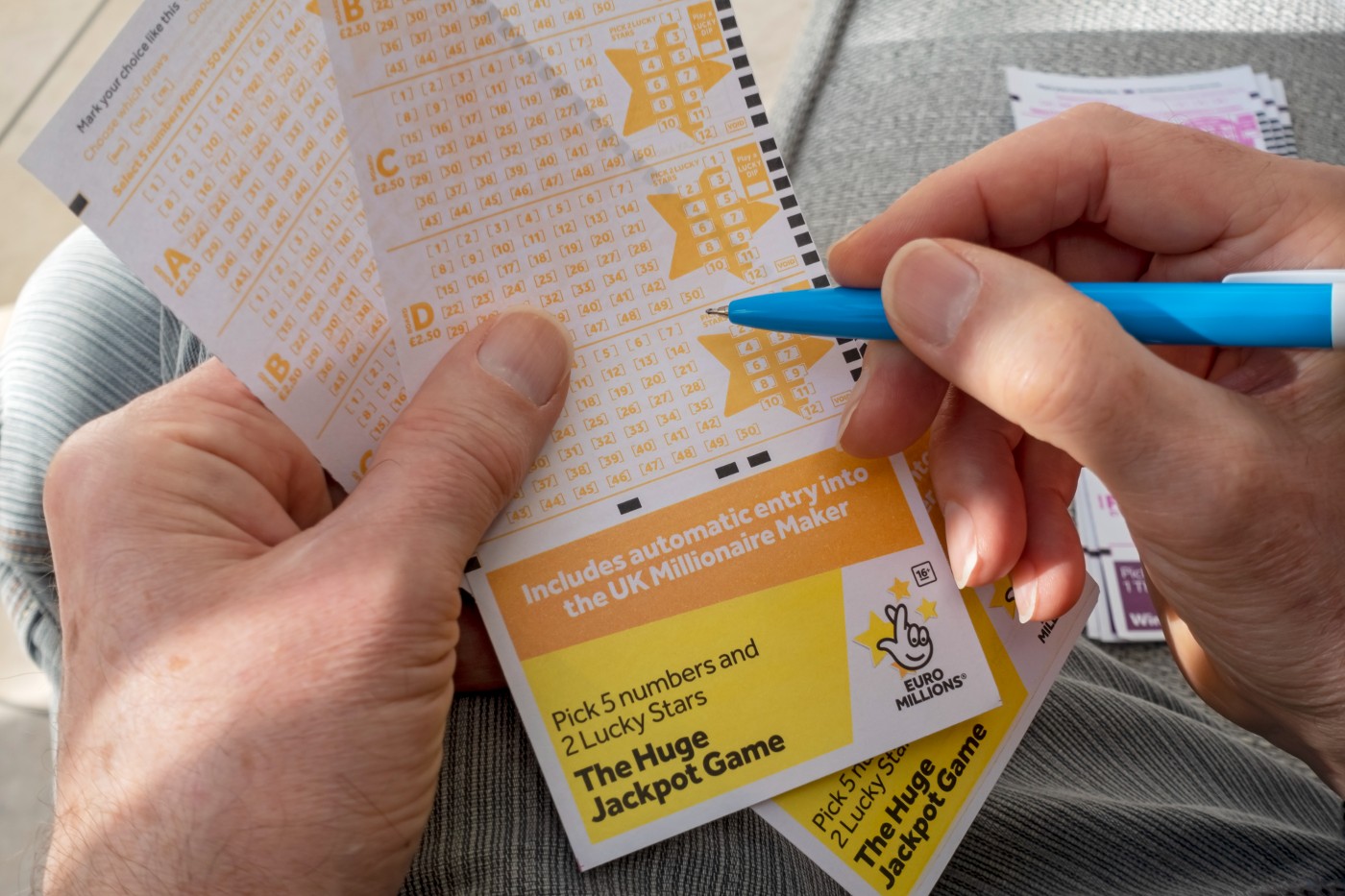

'Angel' visits woman before lottery win

'Angel' visits woman before lottery winTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

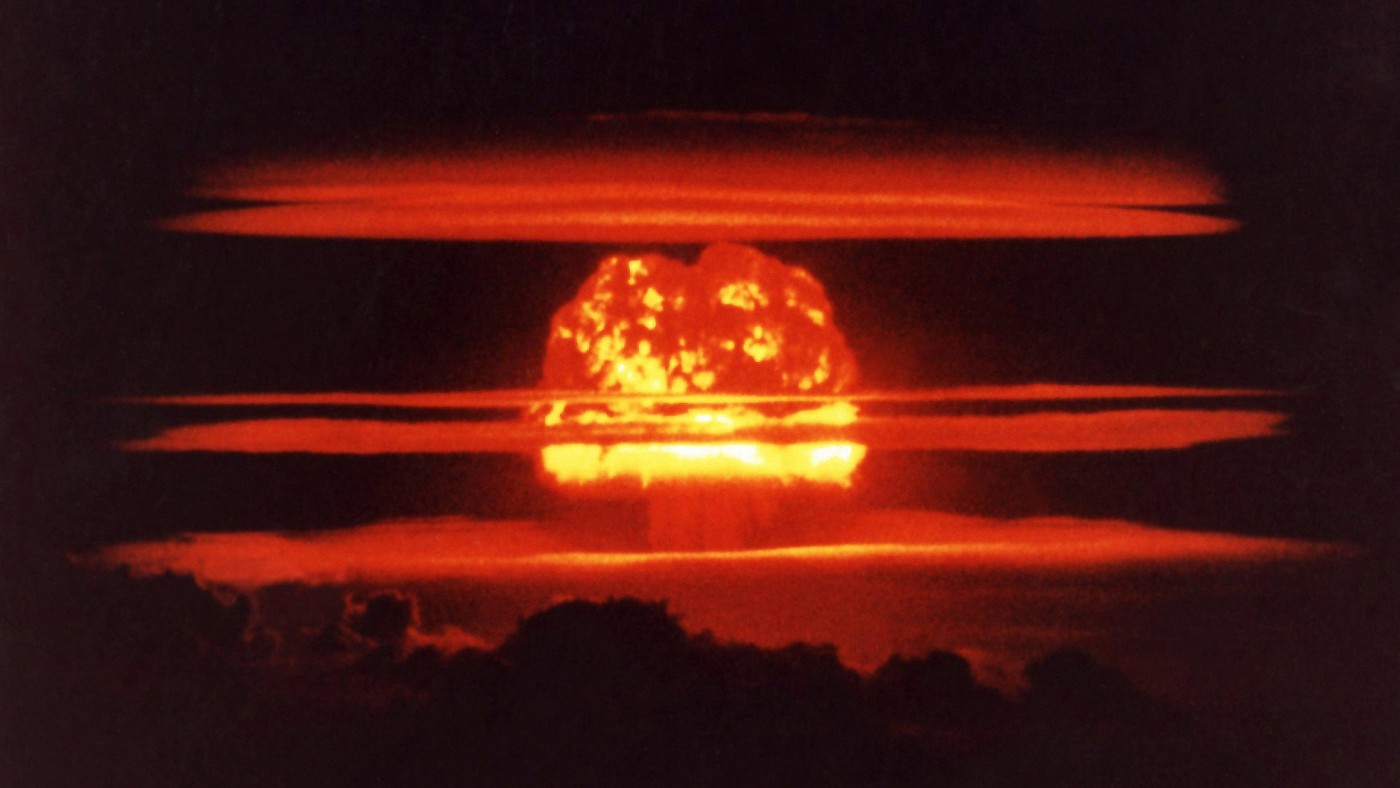

Doomsday group offers 'epic' survival opportunity

Doomsday group offers 'epic' survival opportunityTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

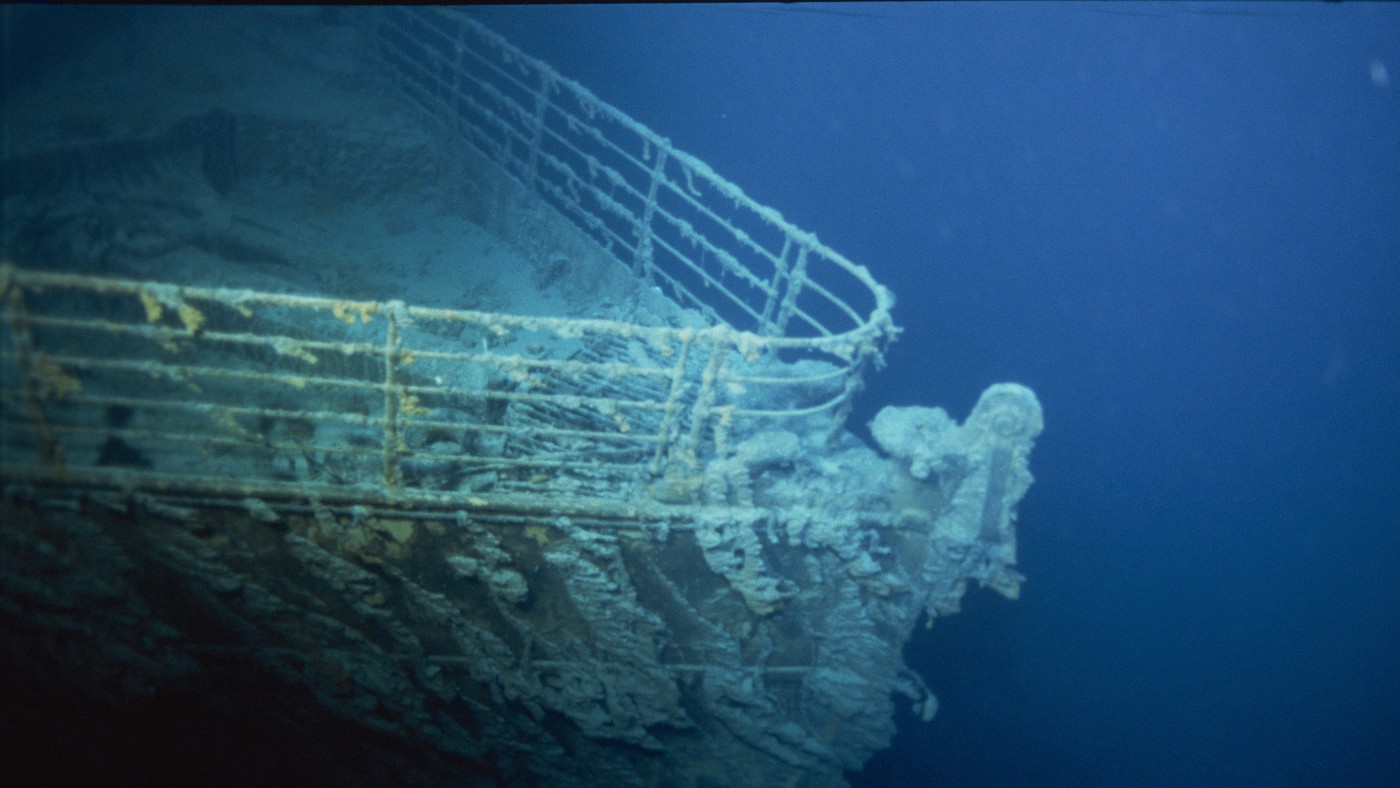

What we know about the Titan sub’s likely implosion

What we know about the Titan sub’s likely implosionfeature Experts say the five passengers would have died ‘instantaneously’ following ‘catastrophic’ loss of pressure

-

What happened to the missing Titanic sub?

What happened to the missing Titanic sub?Today's Big Question Oxygen supplies running out after vessel lost contact during ‘daredevil’ trip

-

Man arrested after shooting himself in the leg

Man arrested after shooting himself in the legfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Scientists have watched the end of the world

Scientists have watched the end of the worldfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Canada’s troubled relationship with its indigenous population

Canada’s troubled relationship with its indigenous populationfeature State grappling with reparations amid accusations of genocides against First Nations people

-

Woman passes driving test at 960th attempt

Woman passes driving test at 960th attemptfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life