Ebola: political correctness first, soldiers’ lives second

Why is Britain risking lives 3,000 miles from home rather than securing its national borders?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The basic instincts of our professional political class have been smothered by the pungent chloroform of political correctness; even basic medical precautions like quarantine take second place to other more right-on considerations.

For Joanna, the heroine of Ira Levin’s spooky novella The Stepford Wives, the first hint that all is not quite what it seems in her supposedly idyllic New England clapboard commuting town is when she asks her neighbour Carol over for coffee one evening. “Thanks, I’d like to,” Carol said, “but I have to wax the family-room floor.”

In response to the threat of Ebola the government has decided to wax the family room floor. Rather than seeking to secure our national borders its first action after a meeting of COBRA last Wednesday was to announce that the UK would be sending a hospital ship, the Fleet Auxiliary Argus, and 750 personnel to West Africa to help contain the medical crisis there.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This was accompanied by the usual moral swank used to justify this government’s plans to spend large sums of taxpayers’ money abroad.

The commanding officer of one military unit, the Royal Scots (the UK’s oldest infantry regiment with the lovely nickname of ‘Pontius Pilate’s bodyguard’) designated to assist in this operation, said: “This is a challenge unlike any, but the point is that we are very well prepared. This kind of operation represents, I think, the future for parts of the British Army.”

Really?

While the courage and commitment of our gallant troops in Iraq and Afghanistan was never in doubt, both campaigns were bedevilled by poor equipment. It took years for the army to procure a mine-proof vehicle; it never had enough helicopters. And although it is a harsh thing to say, it never really mastered its operating environment in Afghanistan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The medical support wasn’t great initially either. In the early years wounded British soldiers who found themselves by chance in the American casevac chain thanked their lucky stars. An American military hospital was infinitely preferable to the dingy horrors of Selly Oak where soldiers severely wounded in battle were treated alongside Saturday night drunks.

So, what are our soldiers’ chances in Sierra Leone? Philippa Tuckman, a solicitor specialising in compensation for soldiers, put it this way in a press interview: “This is a high-risk deployment. We must hope that the training and medical support provided to British troops is adequate to protect them from the virus and only time will tell whether sufficient provision has been put in place.

"The MoD would not want to find itself faced with serious questions about whether it is properly protecting its soldiers from this disease.”

British soldiers are obliged to do many things at the behest of their Queen and country – but risking their lives against the Ebola virus 3,000 miles from home in countries which haven’t been the responsibility of the British government for more than 50 years isn’t one of them.

Meanwhile, 20,000 students from West Africa studying at British universities are arriving back for the start of term. Plans to “screen” potential carriers of the virus at our ports and airports are yet to be finalised even though they appear to involve not much more than a “mickey mouse” questionnaire.

And, of course, our borders remain completely porous to illegal entrants of many kinds. I am willing to put money on the fact that the refugee encampments around Calais full of hopefuls keen to come to the UK will almost certainly become incubation sites for the Ebola virus.

Nigel Farage suggested last week that one of the first things we should do to get a grip of “borderless” Britain should be to exclude HIV-positive foreigners from entering the country. This produced a furious reaction in parts of the media.

But given that a lifetime’s treatment for this condition costs British taxpayers about £1 million, Farage was surely only talking commonsense. But commonsense has been demonised in disease control as in so many other areas of modern British life.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

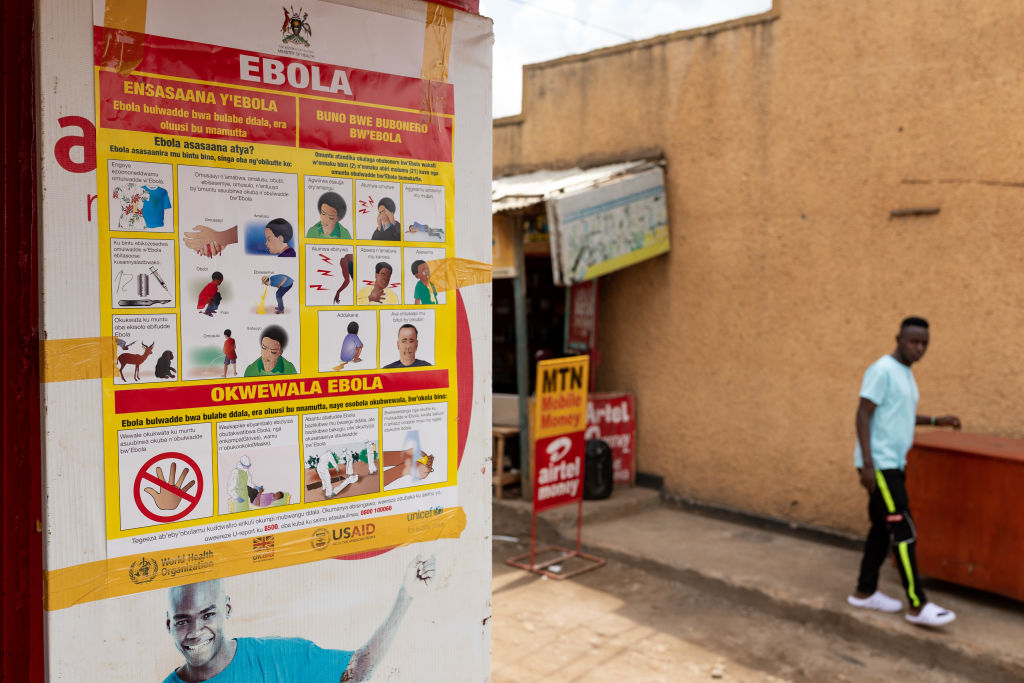

Ebola outbreak leads to 3-week lockdown in two Ugandan districts

Ebola outbreak leads to 3-week lockdown in two Ugandan districtsSpeed Read

-

What will the next pandemic look like – and are we ready?

What will the next pandemic look like – and are we ready?The Explainer Creator of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine warns that future viruses could be more contagious and lethal

-

New Ebola outbreak: what you need to know

New Ebola outbreak: what you need to knowfeature Guinea declares epidemic after first deaths since 2016

-

Ebola has been detected again in eastern Congo

Ebola has been detected again in eastern CongoSpeed Read

-

5 dead after new Ebola outbreak hits Congo

5 dead after new Ebola outbreak hits CongoSpeed Read

-

The fatal viruses that the world has learned to live with

The fatal viruses that the world has learned to live withIn Depth WHO experts say coronavirus may become endemic like HIV

-

How the Ebola epidemic started

How the Ebola epidemic startedIn Depth The ‘largest and most complex’ outbreak since the virus was discovered peaked in 2014–16

-

Ebola outbreak threat rises as first urban case reported

Ebola outbreak threat rises as first urban case reportedSpeed Read